“Before dark,” she reminded him. “Otherwise my neck will be on the chopping block.”

My own instinct was to retort that the British preference was for hanging, but Owain wasn’t prone to such frivolities.

He was greatly tempted to take the stairs back up to the surface but knew it would be a foolish exertion in his present feeble state. He entered the lift.

As I stared at his smeared image in the polished steel wall of the lift I could sense his unease. To me he looked the perfetinldier; he had been raised to it from an early age. Yet he was filled with vague, restless insecurities, not least the nagging anxiety that the lift might at any moment fail and send him plummeting.

His relief was palpable when we emerged at the basement level. We passed down another concrete corridor and went through a storage area with crates piled high on cantilevered shelves. At its far end was a pair of clear plastic doors stuck with black-and-yellow striped tape for the benefit of forklift drivers.

The warehouse was quiet and deserted apart from two elderly men who were crouched around a paraffin stove, sipping a golden brown liquid from glass cups.

“Tea or whisky?” Owain called, surprised at his own levity, which had in fact been prompted by my own instinct to say something.

The men looked back at him with blank incomprehension. I relished a mild sense of victory in my brief display of presence, though I sensed Owain stiffening his control again with a feeling of having spoken out of turn. He viewed the comment as a lax outburst, a mild breach of decorum; he had no inkling I was the originator.

Beyond the doors was an extensive parking space for staff cars and All-Terrain Vehicles. Impacted snow crunched under Owain’s boots as he crossed to a sentry box where two MPs sat, playing cards. They rose and saluted.

He jangled his keys, having already spotted the Land Rover. One of the men waved him on. They’d been expecting him. No doubt Giselle had phoned through.

The vehicle was a left-hand drive of some vintage, the dashboard old-fashioned with its flick switches and analogue dials. He turned the key and the engine chuntered into life. Without delay he drove up the slip road and out onto Whitehall, driving on the right-hand side of the road.

The civilian traffic was sparse, a few long-serving trucks and vans rather than cars. An old double-decker bus went by, ferrying civilians. Its windows were missing and the flaking red paint on its coachwork was almost indistinguishable from the extensive areas of rust. It was followed by a taxicab hand-painted in white and grey, grilles encasing its side windows. A senior officer and a young woman were sitting in the back seat.

Owain drove slowly, in no great hurry. Knots of soldiers and civilians were gathered around the soup kitchens lining the approach to Trafalgar Square, steam billowing from big urns. They looked surprisingly cheerful and were busy bartering food items and medical supplies. A line of people waited at a bus stop, its pole mounted in a concrete-filled drum. The civilians wore all manner of hats and layer on layer of hand-me-down clothing. Most were clutching bulging bags of vegetables and firewood. Dirty snow had been piled on either side of the thoroughfare, barricading buildings with metal shuttered windows. Sandbags and barbed wire framed doorways and forecourts.

Overhead the sky was a marbled grey. Darkness was already beginning to gather. Owain switched on the jeep’s heating. He turned into Trafalgar Square, circling it in an anticlockwise direction. In place of Nelsons Column stood a weathered golden statue of an eagle rampant. The rest of the site had been levelled and was a parking space for snow ploughs and security police wagons. A Cougar battle tank sat in the colonnade of the National Gallery, pigeons perched on its 120mm gun barrel, its slab-faced armour zebra-striped. Soldiers and MPs manned checkpoints all around the square.

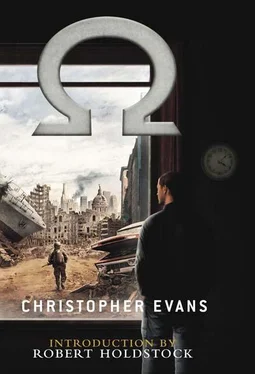

Owain drove on. There were frequent gaps in the street frontages that held nothing but snow-covered rubble. In places the dereliction was extensive. I saw no evidence of what I might have recognised as modern commercial architecture, no sleek high-rises of brick and glass, nothing that looked as if it had been constructed for any purpose other than to withstand a prolonged siege.

Halfway up the Haymarket Owain came to a checkpoint and was directed to pull over. He showed his ID card to an MP. It resembled a credit card, with profile and frontal head shots, a magnetic strip on its rear. The MP told him that if he was headed north he would have to go along Piccadilly and up Park Lane since both Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road were presently closed to traffic. Effectively sealing off all the Soho margins, he thought.

“I’m headed west,” he said, the lie making his pulse surge.

He turned left into Jermyn Street, took a right, and found himself driving straight towards a full-blown roadblock. Temporary signs indicated a left turn only, which would force him west along Piccadilly, away from his intended destination. Instead he drove straight up to the razor-wire barrier.

Ahead of him hoardings around Piccadilly Circus carried patriotic posters featuring images of citizens and soldiers clone in a style that reminded me of Soviet heroic realism. One showed a multiracial group surrounded by a swirl of national flags and a scroll declaring: BROTHERS-IN-ARMS! Among the flags was a red, gold and black banner, its central band surmounted by a black Teutonic cross.

One of the soldiers from the roadblock approached the car. They were CIF men, equipped with Sterling submachine guns and snug hooded winter-camouflage body suits. This one held a senior guard’s rank, equivalent to a sergeant.

Owain surrendered his ID card. The guardsman swiped it through a hand-held scanner before frowning as if it wasn’t working. Or as if it didn’t check out.

“Can I ask where you’re going, sir?”

Owain decided to be direct. “I’d like to take a look at the bomb site.”

The man squinted at him, his eyes shadowed under the cowled brim of his helmet. “And which one would that be, sir?”

He had an Ulster accent; Owain had done a six-month tour of duty there while still an NCO. Suppressing extreme Catholic and Loyalist groups opposed to the Ecumenical Irish Republic.

“Soho,” he replied.

“I have no information on any bomb site, sir.”

“There was an explosion. A few days ago. I mean, a few days before Christmas.”

The man looked studiously blank. “I know nothing about that, sir. I’m afraid the area’s off-limits.”

He was scrupulously formal. Owain knew he wasn’t going to get anywhere unless he raised the stakes.

“Listen,” he said, “I was in Regent Street when it went off. Let me speak to someone.”

The guardsman’s face didn’t change. There were half a dozen of his colleagues at the barricade, all watching.

“Field Marshal Maredudd sent me over,” Owain said. “I’ve come straight from the War Office.”

Another glance at the scanner screen. “As far as I can see, there’s nothing here relating to site access.”

Owain essayed a shrug. “We didn’t imagine it would be a problem. Would I have driven up here otherwise?”

Once again the guardsman scrutinised him against the picture on his ID. “I’m sorry, colonel—”

“It’s major” he said. “Major Owain Maredudd. If I was a spy or a saboteur, you don’t really think I’d fall for that one, do you? Do you want my serial number and my mother’s maiden name?”

The guardsman had the grace to smile.

“Pull in over there,” he said, pointing to an area of waste ground on the corner of Piccadilly. “Oh, and sir?”

“Yes?”

“You might want to switch on your lights.”

Читать дальше