Battlezones. Now that was a title worth considering for the new series. It had a suitable ring of modernity to it.

I swallowed the last of my beer and departed with a mannered wave to the three men.

Five minutes later I slipped into Racing Green and emerged with a heathery V-neck. It was unlikely Rees would ever wear it, his style tending more to sweatshirts and ancient denims, but Lyneth had a mission to civilise him. Rees was a talented software designer specialising in graphical interfaces, and we’d employed him during the making of the series, so for once he wasn’t short of cash. But his personal life was a mess and he was presently living alone in a Peckham bedsit. Lyneth had invited him to spend Christmas Day with us. I doubted he would actually show up.

I spotted a gap in the traffic and sprinted across the road. Two things happened, one after the other. The mobile in my pocket started trilling and I instinctively paused to pull it free. An instant later there was an enormous bang that picked me up and hurled me backwards.

My head hit something—it may have been the body of a car—and I felt a blaze of enveloping pain. I saw the entire front of Hamley’s bulging outwards, dust blossoming and debris cascading down on the swarming street. Darkness swallowed me up.

What followed were snippets of disconnected impressions: the persistent squeaking of a trolley wheel as I was bundled down a corridor; Christmas greetings cards pinned around the frame of a notice board; distant voices blurring in and out of earshot; a taste of stale blood on my bloated tongue. The pain in my head was so intense that it dwarfed everything else, even my fleeting thoughts of Lyneth and the girls. I kept passing out and resurfacing before eventually settling into a more prolonged period of unconsciousness. When I finally woke again I was in another world entirely.

The room was painted a duck-egg green. I lay in a dim light, in a wrought iron bed that was not a modern fashionable type but one of authentic age. My head was raised on a series of pillows with starchy covers. There was the smell of something sooty.

I risked a slight movement of the head, and felt a wave of pain worse than any headache. But it ebbed and I was able to inch myself up from the pillow.

A crimson patchwork quilt lay across the bed. Beyond the foot of the bed was a mirrored dresser on which a tasselled table lamp gave off a dull orange glow. The room looked utilitarian, but the furniture gave it a cosy feel. A computer sat on a drop-leaf table beside the door. It was not switched on, and someone had hung a crocheted doily over its screen. Next to the dresser an area of wall had been hacked out to make a fireplace where coals were burning low in a cast iron grate. Its bricked-in surrounds were crudely finished.

Had I been taken out of hospital? If so, to where? The room was quite unfamiliar to me, though in my drowsy state this didn’t bother me unduly.

The door opened, casting a swathe of brighter light into the room. A squat middle aged woman in a floral dress and black cardigan entered. She came to the bed and, seeing that I was awake, said, “There is water here for your thirst.”

She spoke gruffly, her English heavily accented. I tried to speak, failed.

She filled a tumbler from a glass pitcher on the bedside table, put one hand behind my back and sat me upright. Blood swirled in my head. When my vision cleared I saw that she was holding the tumbler in front of my mouth. She was stocky and swarthy and smelt of mothballs and stale sweat. Her dark eyes regarded me incuriously from what I found myself thinking was a peasant’s face.

I gulped like a child, the water dribbling down my chin. Finally she laid me back on the pillow and swabbed my chin with a scrap of cloth from her cardigan pocket.

“There, there,” she said, giving a gap-toothed smile. “That will be better, yes?”

For a long time after she was gone I just lay there, registering the unfamiliar surroundings with a kind of bleary curiosity. I began to make small movements, growing bolder when none provoked a renewed spasm of head pain. I threw back the covers. Swung my feet down to the floor. Slowly, very slowly, levered myself up until I was standing.

A dull throbbing in the head, nothing more. I glimpsed my nakedness in the mirror as I crossed the room to the window. I began cranking a handle to raise the blind.

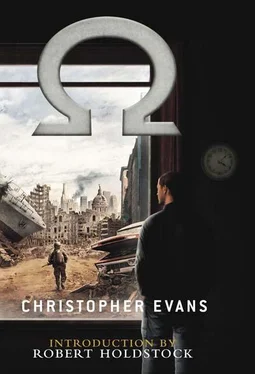

Outside it was dark. No street lamps shone and there were no lights in any of the windows of the shadowy buildings visible across a snow-covered square. They were squat concrete fortresses of slit windows and angular walls, their roofs topped with radar dishes, artillery and missile emplacements. I knew them to be just the surface structures of an extensive underground complex housing all the administrative functions of the state. This was Westminster, the heart of a London I’d never seen before.

And I was in one such building myself, several floors above ground. A fleeting memory came of flying low over the city at night: I’d looked down on the coiled milky band of the frozen Thames, with dark lines of roads and clusters of buildings stretching away on either side. There were extensive areas of mottled whiteness between them. The city’s broken panorama was like a study in monochrome, a photographic negative of something that was familiar yet unfamiliar.

A dim reflection faced me in the window glass. It wasn’t me—not quite. A slimmer, harder-edged version of myself, with cropped hair and a more upright stance. An alter ego, staring back like a not-quite-identical twin.

I heard footsteps outside the room, felt my legs beginning to give way. Somehow I managed to get back to the bed, burying myself under the quilt, letting sleep wash over me like a benedicon.

All that night I dreamt that I kept waking to find myself lying in a modern hospital room, a monitor blinking off to my left. I was propped up under crisp cotton sheets, left alone in the suffocating sterile warmth. It was a fever sleep filled with confusion. At various times I saw two quite distinct women. The first, seated beside the door in the hospital room, was the same age as myself, dark auburn hair framing a sensuous and intelligent face. I couldn’t recall her name, though I knew we had once been lovers. At other times I was back in the green room, attended by a younger woman, sallow skinned and gamin, her black hair tied back in a ponytail. When I woke fully again I was in the wrought iron bed and a man in a white coat was standing beside me.

“Good morning,” he said. “Would you like some breakfast?”

A noise escaped my throat, something between a cough and a clearing of the throat.

“What time is it?”

This was an odd question under the circumstances, but it hadn’t really come from me. The voice was different from my own, huskier, with a stronger Welsh accent.

“Just after eight,” he said. “I’d suggest something light. Some cereal or toast. I’m Tyler, by the way. Sir Gruffydd consigned you to my tender mercies.”

He meant my other self’s uncle. I had an image of a florid, white-haired man in his seventies. A field marshal with a long record of service. His name was spelt in the Welsh fashion—I knew this without knowing how.

“Am I all right?” I heard myself ask.

“You were lucky,” Tyler said. “It’s probably just mild concussion and a few scratches. You should be up and about in a day or two.”

“Was it a bomb?”

“Not my pigeon.” He pulled down one of my eyelids and peered perfunctorily at it. I could smell the nicotine on his yellowed fingers. He was middle-aged, brisk in manner, a horseshoe of greying hair fringing his bald skull. He wore a taupe-coloured shirt and tie under his white coat.

Читать дальше