“Are you comfortable now? Would you like to sit up more? I know how to. Like this. There, isn’t that better?

“And look—this is that same picnic and there’s your father! What a comical face. The colors are so funny on all of these.

“And Bobby here. Oh dear.

“Mother.

“And who is this? It says, ‘I’ve got more where that came from!’ but there’s no name. Is it one of the Schearls? Or somebody that you worked with?

“Here he is again. I don’t think I ever—

“Oh, that’s the car we drove to Lake Hopatcong in, and George Washington was sick all over the back seat. Do you remember that? You were so angry.

“Here’s the twins.

“The twins again.

“Here’s Gary. No, it’s Boz! Oh, no, yes, it’s Gary. It doesn’t look like Boz at all really, but Boz had a little plastic bucket just like that, with a red stripe.

“Mother. Isn’t she pretty in this?

“And here you are together, look. You’re both laughing. I wonder what about. Hm? That’s a lovely picture. Isn’t it? I’ll tell you what, I’ll leave it in here, on top of this letter from …? Tony? Is it from Tony? Well, that’s thoughtful. Oh, Lottie told me to be sure to remember to give you a kiss for her.

“I guess it’s that time. Is it?

“It isn’t three o’clock. I thought it was three o’clock. But it isn’t. Would you like to look at some more of them? Or are you bored? I wouldn’t blame you, having to sit there like that, unable to move a muscle, and listening to me go on. I can rattle. I certainly wouldn’t blame you if you were bored.”

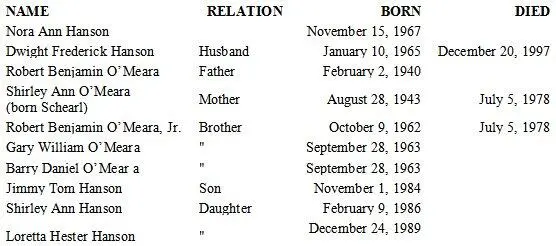

18. The New American Catholic Bible (2021)

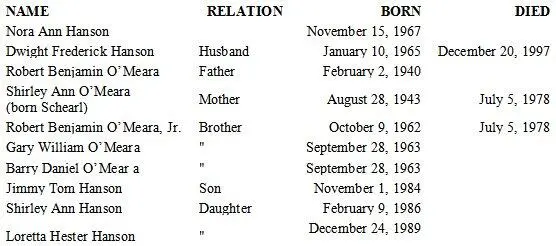

Years before 334, when they’d been living in a single dismal basement room on Mott Street, a salesman had come round selling the New American Catholic Bible, and not just the Bible but a whole course of instructions that would bring her up to date on her own religion. By the time he’d come back to repossess she’d filled in the front pages with all the important dates of the family’s history:

The salesman let her keep the Bible in exchange for the original deposit and an additional five dollars but took back the study plans and the looseleaf binder.

That was 1999. Whenever in later years the family enlarged or contracted she would enroll the fact faithfully in The New American Catholic Bible the very day it happened.

On June 30, 2001, Jimmy Tom was clubbed by the police during a riot protesting the ten o’clock curfew that the President had imposed during the Farm Crisis. He died the same night.

On April 11, 2003, six years after his father’s death. Boz was born in Bellevue Hospital. Dwight had been a member of the Teamsters, the first union to get sperm preservation benefits as a standard feature of its group life policy.

On May 29, 2013, Amparo was born, at 334. Not until she’d mistakenly written down Amparo’s last name as Hanson did she realize that as yet the Bible possessed no record of Amparo’s father. By now, however, the official listing had acquired a kind of shadow of omitted relatives: her own stepmother Sue-Ellen, her endless in-laws, and Shrimp’s two federal contract babies who had been called Tiger (after the cat he’d replaced) and Thumper (after Thumper in Bambi ). Juan’s case was more delicate than any of these, but finally she decided that even though Amparo’s name was Martinez, Lottie was still legally a Hanson, and so Juan was doomed to join the other borderline cases in the margin. The mistake was corrected.

On July 6, 2016, Mickey was born, also at 334.

Then, on March 6, 2011, the nursing home in Elizabeth phoned Williken, who brought the message upstairs that R.B. O’Meara was dead. He had died peacefully and voluntarily at the age of eighty-one. Her father—dead!

As she filled in this new information it occurred to Mrs. Hanson that she hadn’t looked at the religious part of the book since the company had stopped sending her lessons. She reached in at random and pulled out, from Proverbs: “Scorn for the scorners, yes; but for the wretched, grace.”

Later she mentioned this message to Shrimp, who was up to her eyebrows in mysticism, hoping that her daughter would be able to make it mean more than it meant to her.

Shrimp read it aloud, then read it aloud a second time. In her opinion it meant nothing deeper than it said: “Scorn for the scorners, yes; but for the wretched, grace.”

A promise that hadn’t been and obviously wouldn’t be kept. Mrs. Hanson felt betrayed and insulted.

19. A Desirable Job (2021)

Lottie had dropped out in tenth grade after her humanities teacher, old Mr. Sills, had made fun of her legs. Mrs. Hanson never lectured her about going back, certain that the combination of boredom and claustrophobia (these were the Mott Street days) would outweigh wounded pride by the next school-year, if not before. But when fall came Lottie was unrelenting and her mother agreed to sign the permission forms to keep her home. She only had two years of high school herself and could still remember how she’d hated it, sitting there and listening to the jabber or staring at books. Besides it was nice having Lottie about to do all the little nuisance chores—washing, mending, keeping the cats off—that Mrs. Hanson resisted. With Boz, Lottie was better than a pound of pills, playing with him and talking with him hour after hour, year after year.

Then, at eighteen, Lottie was issued her own MODICUM card and an ultimatum: if she didn’t have a full-time job by the end of six months, dependent benefits would stop and she’d have to move to one of the scrap heaps for hard-core unemployables like Roebling Plaza. Coincidentally the Hansons would lose their place on the waiting list for 334.

Lottie drifted into jobs and out of jobs with the same fierce indifference that had seen her through a lifetime at school relatively unscarred. She waited on counters. She sorted plastic beads for a manufacturer. She wrote down numbers that people phoned in from Chicago. She wrapped boxes. She washed and filled and capped gallon jugs in the basement of Bonwit’s. Generally she managed to quit or be fired by May or June, so that she could have a couple months of what life was all about before it was time to die again into the death of a job.

Then one lovely rooftop, just after the Hansons had got into 334, she had met Juan Martinez, and the summertime became official and continuous. She was a mother! A wife! A mother again! Juan worked in the Bellevue morgue with Ab Holt, who lived at the other end of the corridor, which was how they’d happened to coincide on that July roof. He had worked at the morgue for years and it seemed that he would go on working there for more years, and so Lottie could relax into her wife-mother identity and let life be a swimming pool with her season ticket paid in full. She was happy, for a long while.

Not forever. She was a Capricorn, Juan was Sagittarius. From the beginning she’d known it would end, and how. Juan’s pleasures became duties. His visits grew less frequent. The money, that had been so wonderfully steady for three years, for four, almost for five, came in spurts and then in trickles. the family had to make do with Mrs. Hanson’s monthly checks, the supplemental allowance stamps for Amparo and Mickey, and Shrimp’s various windfalls and makeshifts. It reached the point, just short of desperation, where the rent instead of being a nominal $37.50 became a crushing $37.50, and it was at that point that the possibility developed of Lottie getting an incredible job.

Читать дальше