The four noble men (they were ennobled by the circumstance) fell to eating with what, in days of another sort, might almost be called gusto. It was a royal bird and was basted with that concoction of burst fruits and crushed nuts and peppers and ciders and holy oils and reindeer butter that is called—(wait a bit)—

“Do you know that the sheldrake is really a mysterious creature?” Buford Strange asked as he ate noisily (nobody eats such royal fare in quiet). Buford acted as if he knew a secret.

“It is not a mysterious creature at all,” Adrian countered (he knew it was, though). “It is only the common European duck.”

“It is not only the common European duck,” Buford said strongly. “In other days it may be quite uncommon.”

“What are you saying, Buford?” Vincent Rue asked him. “In what other days?”

“Oh, I believe, possibly, in what the Dutch call Kraanzomer, Crane-Summer. Are we agreed that the other days, the days out of count, are topic rather than temporal?”

“We are not even agreed that there are days out of count,” Christopher objected.

“Drakes’ teeth, by the way, while rare, are not unknown,” Adrian Montaigne popped the statement out of his mouth as if in someone else’s voice. He seemed startled at his own words.

“Drake is really the same word as Drakos, a dragon,” Christopher Foxx mumbled. “Ah, I was going to say something else but it is gone now.”

“Waiter, what is the name of the excellent stuff with which the drake is basted and to which it is wedded?” Vincent Rue asked in happy wonder.

“Dragons’ sauce,” said the waiter.

“Well, just what is the mystery, the uncommonness of the sheldrake, Buford?” Christopher asked him.

“I don’t seem to remember,” that man said. “Ah, let us start our discussion with my, our, failure to remember such things. Vincent, did you not have a short paper prepared on ‘Amnesia, the Holes in the Pockets of the Seamless Garment’?”

“I forget. Did I have such a paper prepared? I will look in my own pockets.”

Meanwhile, back on the mountain, back on the thundering mountain there were certain daring and comic persons rushing in and out and counting coup on the Wrath of God. It is a dangerous game. These were the big prophets who prayed so violently and sweated so bloodily and wrestled so strongly. It was they who fought for the salving or the salvation of the days, in fear and in chuckling, in scare-shaking and in laughter-shaking. The thundering mountain was a funny one this morning. It didn’t reach clear to the ground. There was a great space between, and there were eagles flying under it. And the day, the day, was it really the first Monday of Blue-Goose Autumn? Was it really a Monday at all? Or was it a Thursday or an aleikaday?

It was like another morning of not long before. The eagles remember it; the clouds remember it; the mountain wrestlers remember it dimly, though some of the memory has been taken away from them.

Remember how it is written on the holy skins: “If you have faith you shall say to the mountain ‘Remove from here and cast thyself into the sea’ and it will do it.” Well, on that morning they had tried it. Several of the big prophets and wrestlers tried it, for they did have faith. They groaned with travail and joy, they strove mightily, and they did move the mountain and make it cast itself into the sea.

But the thunders made the waters back off. The waters refused to accept or to submerge the mountain. The prayer-men and wrestlers had sufficient faith, but the ocean did not. Whoever had the last laugh on that holy morning?

The strivers were timeless, of the prime age, but they were often called the “grandfathers” brothers’ by the people. They were up there now, the great prophets and prayer-men and wrestlers. One of these intrepid men was an Indian and he was attempting to put the Indian Sign on God himself. God, however, was like a mist and would not be signed.

“We will wrestle,” the Indian said to God in the mist, “we will wrestle to see which of us shall be Lord for this day. I tell you it is not thick enough if only the regular days flow. I hesitate to instruct you in your own business, and yet someone must instruct you. There must be overflowing and special days apart from the regular days. You have such days, I am sure of that, but you keep them prisoned in a bag. It is necessary now that I wrest one of them from you.”

They wrestled, inasmuch as a man slick with his own sweat and blood may wrestle with a mist: and it seemed that the Indian won the lordship of a day from God. “It will be a day of grass,” the Indian said. “It will be none of your dry and juiceless days.” The Indian lay exhausted with his fingers entwined in the won day: and the strength came back to him. “You make a great thing about marking every sparrow’s fall,” the Indian said then. “See that you forget not to mark this day.”

The thing that happened then was this: God marked the day for which they had wrestled, but he marked it on a different holy skin in a different place, not on the regular skin that lists the regular days. This act caused the wrested day to be one of the Days out of Count.

Prophets, wrestlers, praying-men of other sorts were on the mountain also. There were black men who sometimes strove for kaffir-corn days or ivory-tree days. There were brown island men who wrestled for sailfish days or wild-pig days. There were pinkish north-wood men who walked on pine needles and balsam; there were gnarled men out of the swampy lands; there were town men from the great towns. All of these strove with the Lord in fear and in chuckling.

Some of these were beheaded and quartered, and the pieces of them were flung down violently to earth: it is believed that there were certain qualities lacking in these, or that their strength had finally come to an end. But the others, the most of them, won great days from the Lord, Heydays, Halcyon or Kingfisher Days, Maedchensommer Days, St. Garvais Days, Indian Summer Days. These were all rich days, full of joy and death, bubbling with ecstasy and blood. And yet all were marked on different of the holy skins and so they became the Days out of Count.

“Days out of the Count,” Buford Strange was saying. “It’s an entrancing idea, and we have almost proved it. Seasons out of the count! It’s striking that the word for putting a condiment on should be the same word as a division of the year. Well, the seasons out of the count are all well seasoned and spiced. There are whole multiplex layered eras out of the count. The ice ages are such. I do not say ‘were such’; I say ‘are such.’”

“But the ice ages are real, real, real,” Helen Hightower insisted. (Quite a few long hours had passed in the discussions, and now Helen Hightower, the wife of Christopher Foxx, was off her work at the telephone exchange and had put on her glad rags and joined the scholars.)

“Certainly they are real, Helen,” Buford Strange said. “If only I were so real! I believe that you remember them, or know them, more than most of us do. You have a dangerously incomplete amnesia on so many things that I wonder the thunder doesn’t come and take you. But in the days and years and centuries and eras of the straight count there are no ice ages.”

“Well then, how, for instance, would local dwellers account for terminal moraines and glacial till generally?” asked Conquering Sharp-Leaf—ah, Vincent Rue.

(They were at the University, in that cozy room in the psychology department where Buford Strange usually held forth, the room that was just below the special effects room of Professor Timacheff.)

“How did they account for such before the time of modern geology?” Buford asked. “They didn’t. There would be a new boulder one morning that had not been there the day before. The sheep-herder of the place would say that the moon had drawn it out of the ground, or that it had fallen from the sky.”

Читать дальше

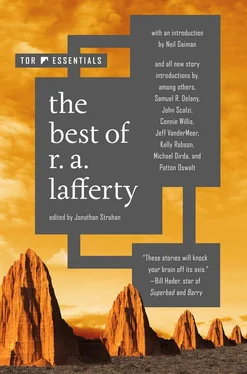

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)