“Is everything possible transferred from the ship to the capsule?” big George Mahoon asked his party.

“It is,” several of them answered.

“I will eat the essence of your capsule-boat just as all of us on Thieving Bear have eaten the essence of your ship,” dead Manbreaker Crag roared.

“Is it sharpened?” Mahoon asked as he took the thick hardwood dowel from the returning Elton Fad.

“It is sharpened,” Elton said, “but something has gone wrong with it. It loses weight as I stand here. They feed across short distances.”

“Scrawny ship captain, I think I’ll eat you as you stand there,” dead Manbreaker roared at Captain Mahoon. “You’d make a big bite, but I’ll eat you.”

Big George Mahoon felled bigger dead-man Manbreaker Crag with a powerful blow to his dead face. Then he put the point of the sharpened dowel pin (“Yes, Elton, I believe that he ate the heart out of it, but how could it have been prevented?” Mahoon asked) to the region of the heart of Manbreaker and struck the pin a heavy blow with the big sledgehammer. But the wooden pin or stake came apart into weak splinters and pieces of worm-eaten (or zombie-eaten) wood.

“Ah well, we’ll have to leave him as he is,” Mahoon said. “I don’t know any other way to kill a man who’s already dead.”

The six explorers got into the capsule-boat then and lifted off. They looked down on the ship they had left behind them then, and it crumbled down and became a part of its own outline and schematic. It became one more of the token spaceships that formed that part-circle that gave the name Plain of the Old Spaceships to that curious site. Those drawn outlines of the old spaceships, they were the old spaceships. There must have been a lot of good eating in each of them, though.

“To the log!” George Mahoon howled. “I feel it all slipping out of my memory so fast! Each one of us take a long log page and write as rapidly as possible. Get it down, before we lose it as earlier explorers lost it.”

“No use lamenting that there is no ‘ink’ in any stylus or pen or log pencil laid out or still boxed,” Selma Last-Rose rattled. “No use lamenting that even the electronic ink is eaten out of every recorder and that the remembering jelly is eaten out of every memory pot. The hungers of the Thieving Bears are unaccountable. All the earlier logs had a few words written in something other than ink. If we all write as fast as we can, we may get more than a few words down. We may even get the explanation down onto the log sheets before it fades completely from our minds.”

They all opened their veins and wrote on the long log sheets in their own blood. It was sticky going. So many free-flowing things had been eaten out of their blood that it was now viscous and thick. But they made it do. They got the explanation all down, even though (when it was shown to them later) they hardly remembered writing it.

A simple explanation had been needed for the conditions on Thieving Bear Planet. It was needed because, as the great Reginald Hot had once phrased it, “Anomalies are messy.”

And that simple explanation is herewith given, more or less as it was written in thick blood in the log book.

DAYS OF GRASS, DAYS OF STRAW

Introduction by Gary K. Wolfe

“Days of Grass, Days of Straw” first appeared in New Dimensions 3, the third in a series of rather adventurous anthologies edited by Robert Silverberg throughout the 1970s. Coming close on the heels of science fiction’s controversial New Wave, Silverberg’s series was clearly out to recognize new voices and new literary approaches to science fiction and fantasy, and Lafferty had stories in each of the first four volumes. The volume with “Days of Grass, Days of Straw” also included two stories which would become widely reprinted, Hugo Award–winning classics, Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” and James Tiptree, Jr.’s “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” (Tiptree was of course later revealed to be a pseudonym of Alice Sheldon). Each of those would be reprinted dozens of times in the coming decades, but Lafferty’s story—despite now being regarded as one of his best and most strikingly visionary by aficionados—was reprinted only in a few of his own collections. It did, however, get translated into Dutch and inspired the 2004 song Dagen van gras, dagen van stro (a literal translation of the title) by the performer Spinvis (Erik de Jong). Spinvis’s lyrics have only an elliptical connection with Lafferty’s story, but the point is that Lafferty’s best stories, even when not widely familiar, manage to find their way into unexpected corners of the culture and leave traces there.

The story itself is one that some readers find challenging—within the first two lines, a city street morphs into a road, then a trail, then a mere path, and our protagonist Christopher finds himself in a pre-urban, pre-industrial landscape with features resembling Native American legends and Oklahoma tall tales. Even his own name doesn’t ring true, and half-recognized people and places never quite coalesce into a more traditionally realized fantasy landscape. Yet he feels revived and invigorated, as though the world had been “pumped full of new juice.” “Things were mighty odd here,” he notices in an observation that may well sound familiar to anyone reading a Lafferty story for the first time. “There was just a little bit of something wrong about things.”

We eventually learn that Christopher hasn’t crossed into a fantasy world at all, but rather to a different kind of time—a “day of grass,” one of the “overflowing and special days apart from the regular days,” which are called days of straw. Although these special days are “Days out of Count” in terms of history and the calendar, they are earned at great cost by prophets and “prayer-men,” who wrestle with God to gain them. Called by different names in different cultures, these “rich days, full of joy and death, bubbling with ecstasy and blood” may include entire seasons, and although “nobody has direct memory of being in them or living in them,” we give them pallid names like Indian Summer. Lafferty’s stunning vision of a more vital and perhaps more dangerous world just beyond the one we know, but somehow folded into it, is one of his most haunting recurrent themes.

Days of Grass, Days of Straw

Fog in the corner and fog in his head:

Gray day broken and bleeding red.

—Henry Drumhead,

Ballads

Christopher Foxx was walking down a city street. No, it was a city road. It was really a city trail or path. He was walking in a fog, but the fog wasn’t in the air or the ambient: it was in his head. Things were mighty odd here. There was just a little bit of something wrong about things.

Oceans of grass for one instance. Should a large and busy city (and this was clearly that) have blue-green grass belly-high in its main street? Things hardly remembered: echoes and shadows, or were they the strong sounds and things themselves? Christopher felt as though his eyeballs had been cleaned with a magic cleaner, as though he were blessed with new sensing in ears and nose, as though he went with a restored body and was breathing a new sort of air. It was very pleasant, but it was puzzling. How had the world been pumped full of new juice?

Christopher couldn’t recall what day it was; he certainly didn’t know what hour it was. It was a gray day, but there was no dullness in that gray. It was shimmering pearl-gray, of a color bounced back by shimmering water and shimmering air. It was a crimson-edged day, like a gray squirrel shot and bleeding redly from the inside and around the edges. Yes, there was the pleasant touch of death on things, gushing death and gushing life.

Читать дальше

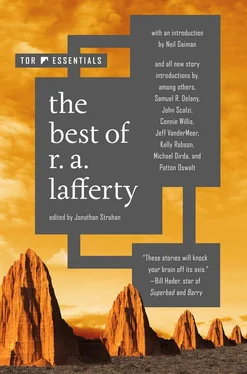

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)