Balauros, Kalo, Manusch, Melelo, Tsigani, Moro, Romani, Flamenco, Sinto, Cicara, the many-named people was traveling in its thousands. The Romani Rai was moving.

Two million Gypsies of the world were going home.

At the institute, Gregory Smirnov was talking to his friends and associates.

“You remember the thesis I presented several years ago,” he said, “that, a little over a thousand years ago, Outer Visitors came down to Earth and took a sliver of our Earth away with them. All of you found the proposition comical, but I arrived at my conclusion by isostatic and eustatic analysis carried out minutely. There is no doubt that it happened.”

“One of our slivers is missing,” said Aloysius Shiplap. “You guessed the sliver taken at about ten thousand square miles in area and no more than a mile thick at its greatest. You said you thought they wanted to run this sliver from our Earth through their laboratories as a sample. Do you have something new on our missing sliver?”

“I’m closing the inquiry,” Gregory said. “They’ve brought it back.”

It was simple really, jekvasteskero, Gypsy-simple. It is the gadjo, the non-Gypsies of the world, who give complicated answers to simple things.

“They came and took our country away from us,” the Gypsies had always said, and that is what had happened.

The Outer Visitors had run a slip under it, rocked it gently to rid it of nervous fauna, and then taken it away for study. For a marker, they left an immaterial simulacrum of that high country as we ourselves sometimes set name or picture tags to show where an object will be set later. This simulacrum was often seen by humans as a mirage.

The Outer Visitors also set simulacra in the minds of the superior fauna that fled from the moving land. This would be a homing instinct, inhibiting permanent settlement anywhere until the time should come for the resettlement; entwined with this instinct were certain premonitions, fortune-showings, and understandings.

Now the Visitors brought the slice of land back, and its old fauna homed in on it.

“What will the—ah—patronizing smile on my part—Outer Visitors do now, Gregory?” Aloysius Shiplap asked back at the Institute.

“Why, take another sliver of our Earth to study, I suppose, Aloysius,” Gregory Smirnov said.

Low-intensity earthquakes rocked the Los Angeles area for three days. The entire area was evacuated of people. Then there was a great whistle blast from the sky as if to say, “All ashore that’s going ashore.”

Then the surface to some little depth and all its superstructure was taken away. It was gone. And then it was quickly forgotten.

From the Twenty-second Century Comprehensive Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, page 389:

ANGELENOS. (See also Automobile Gypsies and Prune Pickers .) A mixed ethnic group of unknown origin, much given to wandering in automobiles. It is predicted that they will be the last users of this vehicle, and several archaic chrome-burdened models are still produced for their market. These people are not beggars; many of them are of superior intelligence. They often set up in business, usually as real estate dealers, gamblers, confidence men, managers of mail-order diploma mills, and promoters of one sort or other. They seldom remain long in one location.

Their pastimes are curious. They drive for hours and days on old and seldom-used cloverleafs and freeways. It has been said that a majority of the Angelenos are narcotics users, but Harold Freelove (who lived for some months as an Angeleno) has proved this false. What they inhale at their frolics (smog-crocks) is a black smoke of carbon and petroleum waste laced with monoxide. Its purpose is not clear.

The religion of the Angelenos is a mixture of old cults with a very strong eschatological element. The Paradise Motif is represented by reference to a mystic “Sunset Boulevard.” The language of the Angelenos is a colorful and racy argot. Their account of their origin is vague:

“They came and took our dizz away from us,” they say.

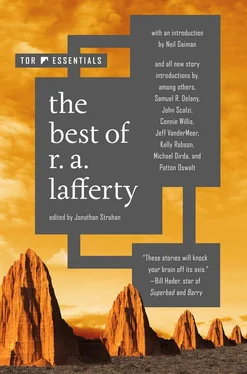

Afterword by Gregory Frost

In 1967 Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions was first published by Doubleday. I, in high school in Iowa and already devouring the likes of Fredric Brown, Bradbury, Heinlein, Asimov, Zelazny, and Dick, might as well have been the target Harlan put in the crosshairs. In retrospect we peer through many great annual Best of anthologies—edited by Gardner Dozois, David Hartwell, Ellen Datlow, Terri Windling, Kelly Link & Gavin Grant, Terry Carr, etc.—and we forget how monumental was Harlan’s lashing together of what he termed “Thirty-two Soothsayers.” I’m near Philadelphia now, and so I think of Harlan as the Albert Barnes of science fiction. Barnes’ collection of impressionists is an extraordinary thing; and to be fair there are a few disappointing works hanging among the Matisses, Van Goghs, Gaunguins, Picassos, and Renoirs—lesser paintings by artists who faded into obscurity, though obviously Barnes thought he saw something in them. Dangerous Visions really is the Barnes collection of science fiction. A few “what happened to…” pieces, but otherwise breathtaking.

Dangerous Visions proved to be my gateway into the worlds of Raphael Aloysius Lafferty through the story Harlan selected, called “Land of the Great Horses.” I did not know at the time how extraordinary that would prove to be, just as I didn’t know that Lafferty himself was a fellow Iowan (born in the southwestern town of Neola, Iowa—if anyone from Neola is reading this, you need to put up at least a plaque for Heaven’s sake!)

As Lafferty stories go, this one is short and seemingly simple, but oh, by the end it has shape-shifted on you more than once. It can be read, in a way, as a companion story to another tale of his called “Narrow Valley,” also concerned with unreliable topography.

It is also exemplary of the way Lafferty entered stories sidewise, producing a text that dives straight into a situation already in motion and seems to be about one thing, yet turns out to be about something else. And then when you think you have its measure, the author adds a punch line you never saw coming.

Here, we begin with a sort of dictum: “They came and took our country away from us,” the people had always said. But nobody understood them.

What country and what people, we must read to discover. We are then introduced to two Englishmen, Richard Rockwell and Seruno Smith, driving across the Thar Desert, which is to say the Great Desert of India. They approach and behold a famous mirage called the Land of the Great Horses, or Diz Boro Grai . It’s what they’ve come to see. Things immediately start to go wrong. In this extremely barren desert, they hear the sound of thunder from an approaching storm, and then find their mirage shot with lightning. The improbable climatic event seems to transform Seruno Smith: he suddenly and inexplicably knows the names of places (a draw called Kuti Tavdavi, Little River); he bursts into song in tongues he does not speak. When asked how by Rockwell, he explains that he has only to remember these tongues to sing, and that “They all cluster around the boro jib itself.” Smith seems to be leading this “great life” out of nowhere. He confesses to Rockwell that he speaks all languages in play—the so-called Seven Sisters, but Smith names only six. Rockwell notices and finally requests the name of the missing language: Deep Romany. Rockwell tries to head back, but Smith refuses, and calls him “Sarishan,” or “English,” as if they are suddenly foreign to each other, and then begins to scale the heights that until moments ago were part of the mirage.

Читать дальше

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)