What was that sound—too slight, too scattered to be a noise? It was like a billion microbes laughing. It was the hilarity of little things waking up to a high time.

“Who is the oldest of all?” Ceran demanded, for their laughter bothered him. “Who is the oldest and first?”

“I am the oldest, the ultimate grandmother,” one said gaily. “All the others are my children. Are you also of my children?”

“Of course,” said Ceran, and the small laughter of unbelief flittered out from the whole multitude of them.

“Then you must be the ultimate child, for you are like no other. If you be, then it is as funny at the end as it was in the beginning.”

“How was it in the beginning?” Ceran bleated. “You are the first. Do you know how you came to be?”

“Oh, yes, yes,” laughed the ultimate grandmother, and the hilarity of the small things became a real noise now.

“How did it begin?” demanded Ceran, and he was hopping and skipping about in his excitement.

“Oh, it was so funny a joke the way things began that you would not believe it,” chittered the grandmother. “A joke, a joke!”

“Tell me the joke, then. If a joke generated your species, then tell me that cosmic joke.”

“Tell yourself,” tinkled the grandmother. “You are a part of the joke if you are of my children. Oh, it is too funny to believe. How good to wake up and laugh and go to sleep again.”

Blazing green frustration! To be so close and to be balked by a giggling bee!

“Don’t go to sleep again! Tell me at once how it began!” Ceran shrilled, and he had the ultimate grandmother between thumb and finger.

“This is not Ritual,” the grandmother protested. “Ritual is that you guess what it was for three days, and we laugh and say, ‘No, no, no, it was something nine times as wild as that. Guess some more.’”

“I will not guess for three days! Tell me at once or I will crush you,” Ceran threatened in a quivering voice.

“I look at you, you look at me, I wonder if you will do it,” the ultimate grandmother said calmly.

Any of the tough men of the Expedition would have done it—would have crushed her, and then another and another and another of the creatures till the secret was told. If Ceran had taken on a tough personality and a tough name he’d have done it. If he’d been Gutboy Barrelhouse he’d have done it without a qualm. But Ceran Swicegood couldn’t do it.

“Tell me,” he pleaded in agony. “All my life I’ve tried to find out how it began, how anything began. And you know!”

“We know. Oh, it was so funny how it began. So joke! So fool, so clown, so grotesque thing! Nobody could guess, nobody could believe.”

“Tell me! Tell me!” Ceran was ashen and hysterical.

“No, no, you are no child of mine,” chortled the ultimate grandmother. “Is too joke a joke to tell a stranger. We could not insult a stranger to tell so funny, so unbelieve. Strangers can die. Shall I have it on conscience that a stranger died laughing?”

“Tell me! Insult me! Let me die laughing!” But Ceran nearly died crying from the frustration that ate him up as a million bee-sized things laughed and hooted and giggled:

“Oh, it was so funny the way it began!”

And they laughed. And laughed. And went on laughing … until Ceran Swicegood wept and laughed together, and crept away, and returned to the ship still laughing. On his next voyage he changed his name to Blaze Bolt and ruled for ninety-seven days as king of a sweet sea island in M-81, but that is another and much more unpleasant story.

I first encountered “Nine Hundred Grandmothers” in The Norton Book of Science Fiction, edited by Ursula K. Le Guin and Brian Attebery with Karen Joy Fowler, an anthology that turned out to be important to my fiction-writing career. It was published in fall 1993, during my first year in the graduate creative-writing program at North Carolina State University. I don’t think I bought a copy immediately, but in January 1994 I had my first workshop with Nebula Award winner John Kessel, who peered at my manuscript and peered at me and peered at my manuscript again and said, “There’s a long, rich history of this sort of thing, and you’re part of it whether you know it or not.”

From that point Kessel was my sensei, and on his recommendation I snapped up a copy of the Norton —a box of marvels that tells a novice SF writer, “You can do anything you want, as long as it’s strange.” When I flew to the Clarion West Writers Workshop that summer, also on Kessel’s recommendation, the Norton was one of the two inspirational hardcovers in my luggage. (The other was Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! for which I never will be asked to write an introduction.)

Of all the stories in the Norton that spoke directly to me, “Nine Hundred Grandmothers” may have spoken the loudest. In her Norton essay, Le Guin discusses science fiction’s tendency to literalize metaphors, and Lafferty’s story precisely literalizes one of the foundational metaphors of my upbringing in rural South Carolina, where I was taught to venerate a long chain of ancestors growing ever smaller as they receded into the distance. Their secrets were closely guarded, but as I stumbled through the late twentieth century, those generations were often audible in the background, like peepers in the spring; I was pretty sure they were laughing. Moreover, all my important ancestors, the conveyors of culture and especially language, seemed to be women. Lafferty’s unforgettable “living dolls” of the planet Proavitus (Latin for “ancestral,” I’m told) embody the famous Faulkner line from Requiem for a Nun : “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Rereading Lafferty’s story now, I wonder about the fate of the Proavitoi. What happens to them in the space between the story’s last two sentences? “With the pharmacopoeia that one could pick up here, a man need never die,” says Manbreaker Crag, who envisions his team becoming “the patent medicine kings of the universe.” Will these “slight people” survive Manbreaker’s unstranding of their organic chemistry? Consider that Lafferty was a lifelong resident of Oklahoma—a state wrested from the natives by any number of Manbreaker Crags—and many of his writings ponder the exploitation of the indigenous peoples of North America; along with language itself, it is the unavoidable theme of his great novel, Okla Hannali .

I believe Lafferty knows exactly what happens to the Proavitoi, but spares us at the end by diverting our attention to “another and much more unpleasant story.” As the ultimate grandmother might have said, was too joke a joke to tell a stranger, perhaps; Lafferty could not insult a stranger to tell so funny, so unbelieve.

Introduction by Harlan Ellison™

Look out your window. What do you see? The gang fight on the corner, with the teenie-boppers using churchkeys on each other’s faces; the scissors grinder with his multicolored cart and tinkling bells; a pudgy woman in a print dress too short for her fat legs, hoeing her lawn; a three-alarm fire with children trapped on the fifth story; a mad dog attached to the leg of a peddler of Seventh Day Adventist literature; an impending race riot with a representative of RAM on a sound truck. Any or all? It takes no special powers of observation to catalog the unclassifiable. But now look again. What do you see? What you usually see? An empty street. Now catalog:

Curbstones, without which cars would run up onto front lawns. Mailboxes, without which touch with the world would be diminished. Telephone poles and wires, without which communication would screech to a halt. Gutters, sewers, and manholes, without which you would be flooded when it rains. Blacktop, without which the car you own wouldn’t last a month on the crushed rock. The breeze, without which, well, a day is diminished. What are these things? They are the obvious. So obvious they become invisible. How many water hydrants and mailboxes did you pass today? None? Hardly. You passed dozens, but you did not see them. They are the incredibly valuable, absolutely necessary, totally ignored staples of a well-run community.

Читать дальше

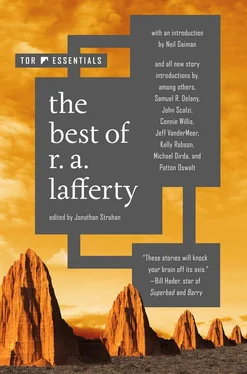

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)