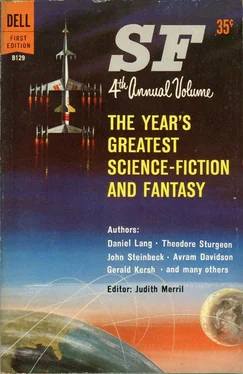

Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1959, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1959

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Watching his face during the big laughs—yocks, the knowledgeable columnists and critics called them—had become a national pastime. Though the contagion of laughter was in his voice and choice of phrase, he played everything deadpan. A small, wiry man with swift nervous movements, he had a face-by-the-million: anybody’s face. Its notable characteristics were three: thin lips, masked eyes, impenetrable as onyx, and astonishing jug-handle ears. His voice was totally flexible, capable of almost any timbre, and with the falsetto he frequently affected, his range was slightly over four octaves. He was an accomplished ventriloquist, though he never used the talent with the conventional dummy, but rather to interrupt himself with strange voices. But it was his ordinary, unremarkable, almost immobile face which was his audience’s preoccupation. His face never laughed, though in dialogue his voice might. His voice could smile, too, even weep, and his face did not. But at the yock, if it was a big yock, a long one, his frozen waiting face would twitch; the thin lips would fill out a trifle: he’s going to smile, he’s going to smile! Sometimes, when the yock was especially fulsome, his mouth actually would widen a trifle; but then it was always time to go on, and, deadpan, he would. What could it matter to anyone whether or not one man in the world smiled? On the face of it, nothing: yet millions of people, most of whom were unaware of it, bent close to their trideo walls and peered raptly, waiting, waiting to see him smile.

As a result, everyone who heard him, heard every word.

Iris found herself grateful, somehow—able to get right out of herself, sweep in with that vast unseen crowd and leave herself, her worrying self, her angry, weary, logical, Nobel-prizewinning self asprawl on the divan while she hung on and smiled, hung on and tittered, hung on and exploded with the world.

He built, and he built, and the trideo cameras crept in on him until, before she knew it, he was standing as close to the invisible wall as belief would permit; and still he came closer, so that he seemed in the room with her; and this was a pyramid higher than most, more swiftly and more deftly built, so that the ultimate explosion could contain itself not much longer, not a beat, not a second. . . .

And he stopped in mid-sentence, mid-word, even, and, over at the left, fell to one knee and held out his arms to the right. “Come on, honey,” he said in a gentle, tear-checked purr.

From the right came a little girl, skipping. She was a beautiful little girl, a picture-book little girl, with old-fashioned bouncing curls, shiny black patent-leather shoes with straps, little white socks, a pale-blue dress with a very wide, very short skirt.

But she wasn’t skipping, she was limping. She almost fell, and Heri was there to catch her.

Holding her in his arms, while she looked trustingly up into his face, he walked to center stage, turned, faced the audience. His eyes were on her face; when he raised them abruptly to the audience, they were, by some trick of the light (or of Heri Gonza) unnaturally bright.

And he stood, that’s all he did, for a time, stood there with the child in his arms, while the pent-up laughter turned to frustrated annoyance, directed first at the comedian, and slowly, slowly, with a rustle of sighs, at the audience itself by the audience. Ah, to see such a thing and be full of laughter: how awful I am. I’m sorry. I’m sorry.

One little arm was white, one pink. Between the too-tiny socks and the too-short skirt, the long thin legs were one white, one pink.

“This is little Koska,” he said after an age. The child smiled suddenly at the sound of her name. He shifted her in his elbow so he could stroke her hair. He said softly, “She’s a little Esthonian girl, from the far north. She doesn’t speak very much English, so she won’t mind if we talk about her.” A huskiness crept into his voice. “She came to us only yesterday. Her mother is a good woman. She sent her to us the minute she noticed.”

Silence again, then he turned the child so their faces were side by side, looking straight into the audience. It was hard to see at first, and then it became all too plain—the excessive pallor of the right side of her face, the too-even flush on the left, and the sharp division between them down the center.

“We’ll make you better,” he whispered. He said it again in a foreign language, and the child brightened, smiled trustingly into his face, kept her smile as she faced the audience again: and wasn’t the smile a tiny bit wider on the pink side than on the white? You couldn’t tell . . .

“Help me,” said Heri Gonza. “Help her, and the others, help us. Find these children, wherever in the world they might be, and call us. Pick up any telephone in the world and say simply, I . . . F. That’s IF, the Iapetitis Foundation. We treat them like little kings and queens. We never cause them any distress. By trideo they are in constant touch with their loved ones.” Suddenly, his voice rang. “The call you make may find the child who teaches us what we need to know. Your call— yours! —may find the cure for us.”

He knelt and set the child gently on her feet. He knelt holding her hands, looking into her face. He said, “And whoever you are, wherever you might be, you doctors, researchers, students, teachers ... if anyone, anywhere, has an inkling, an idea, a way to help, any way at all—then call me. Call me now, call here—” He pointed upward and the block letters and figures of the local telephone floated over his head—”and tell me. I’ll answer you now, I’ll personally speak to anyone who can help. Help, oh, help.”

The last word rang and rang in the air. The deep stage behind him slowly darkened, leaving the two figures, the kneeling man and the little golden girl, flooded with light. He released her hands and she turned away from him, smiling timidly, and crossed the wide stage. It seemed to take forever, and as she walked, very slightly she dragged her left foot.

When she was gone, there was nothing left to look at but Heri Gonza. He had not moved, but the lights had changed, making of him a luminous silhouette against the endless black behind him . . . one kneeling man, a light in the universal dark . . . hope . . . slowly fading, but there, still there . . . no? Oh, there . . .

A sound of singing, the palest of pale blue stains in deep center. The singing up, a powerful voice from the past, an ancient, all but forgotten tape of one of the most moving renditions the world has ever known, especially for such a moment as this: Mahalia Jackson singing The Lord’s Prayer, with the benefit of such audio as had not been dreamed of in her day . . . with a cool fresh scent, with inaudible quasi-hypnotic emanations, with a whispering chorus, a chorus that angels might learn from.

Heri Gonza had not said, “Let us pray.” He would never do such a thing, not on a global network. There was just the kneeling dimness, and the blue glow far away in the black. And if at the very end the glow looked to some like the sign of the cross, it might have been only a shrouded figure raising its arms; and if this was benediction, surely it was in the eye of the beholder. Whatever it was, no one who saw it completely escaped its spell, or ever forgot it. Iris Barran, for one, exhausted to begin with, heart and mind full to bursting with the tragedy of iapetitis; Iris Barran was wrung out by the spectacle. All she could think of was the last spoken word: Help!

She sprang to her phone and waved it active. With trembling fingers she dialed the number which floated in her mind as it had on the trideo wall, and to the composed young lady who appeared in her solido cave, saying, “Trideo, C. A. O. Good evening,” she gasped, “Heri Gonza —quickly.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.