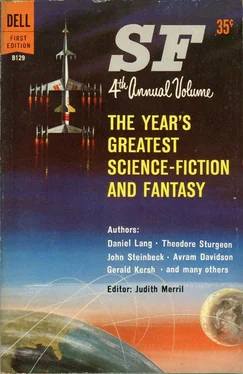

Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1959, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1959

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Captain Swope found out, but Captain Swope did not tell. Something happened to his Fafnir on Iapetus. His signals were faintly heard through the roar of an electrical disturbance on the parent world, and they were unreadable, and they were the last. Then, voiceless, he returned, took up his braking orbit, and at last came screaming down out of the black into and through the springtime blue. His acquisition of the tail-down attitude so very high—over fifty miles—proved that something was badly wrong. The extreme deliberation with which he came in over White Sands, and the constant yawing, like that of a baseball bat balanced on a fingertip, gave final proof that he was attempting a landing under manual control, something never before attempted with anything the size of a Fafnir. It was superbly done, and may never be equaled, that roaring drift down and down through the miles, over forty-six of them, and never a yaw that the sensitive hands could not compensate, until that last one.

What happened? Did some devil-imp of wind, scampering runt of a hurricane, shoulder against the Fafnir? Or was the tension and strain at last too much for weary muscles which could not, even for a split second, relax and pass the controls to another pair of hands? Whatever it was, it happened at three and six-tenths miles, and she lay over bellowing as her pilot made a last desperate attempt to gain some altitude and perhaps another try.

She gained nothing, she lost a bit, hurtling like a dirigible gone mad, faster and faster, hoping to kick the curve of the earth down and away from her, until, over Arkansas, the forward section of the rocket liner—the one which is mostly inside the ship—disintegrated and she blew off her tail. She turned twice end over end and thundered into a buckwheat field.

Two days afterward a photographer got a miraculous picture. It was darkly whispered later that he had unforgivably carried the child—the three-year-old Tresak girl from the farm two miles away—into the crash area and had inexcusably posed her there; but this could never be proved, and anyway, how could he have known? Nevertheless, the multiple miracles of a momentary absence of anything at all in the wide clear background, of the shadows which mantled her and of the glitter of the many-sharded metal scrap which reared up behind her to give her a crown—but most of all the miracle of the child herself, black-eyed, golden-haired, trusting, fearless, one tender hand resting on some jagged steel which would surely shred her flesh if she were less beautiful—these made one of the decade’s most memorable pictures. In a day she was known to the nation, and warmly loved as a sort of infant phoenix rising from the disaster of the roaring bird; the death of the magnificent Swope could not cut the nation quite as painfully because of her, as that cruel ruin could not cut her hand.

The news, then, that on the third day after her contact with the wreck of the ship from Iapetus, the Tresak child had fallen ill of a disfiguring malady never before seen on earth, struck the nation and the world a dreadful and terrifying blow. At first there was only a numbness, but at the appearance of the second, and immediately the third cases of the disease, humanity sprang into action. The first thing it did was to pass seven Acts, an Executive Order and three Conventions against any further off-earth touchdowns; so, until the end of the iapetitis epidemic, there was an end to all but orbital space flight.

“You’re going to be all right,” she whispered, and bent to kiss the solemn, comic little face. (They said it wasn’t contagious; at least, adults didn’t get it.) She straightened up and smiled at him, and Billy smiled his half-smile—it was the left half—in response. He said something to her, but by now his words were so blurred that she failed to catch them. She couldn’t bear to have him repeat whatever it was; he seemed always so puzzled when people did not understand him, as if he could hear himself quite plainly. So to spare herself the pathetic pucker which would worry the dark half of his face, she only smiled the more and said again, “You’re going to be all right,” and then she fled.

Outside in the corridor she leaned for a moment against the wall and got rid of the smile, the rigid difficult hypocrisy of that smile. There was someone standing there on the other side of the scalding blur which replaced the smile; she said, because she had to say it to someone just then: “How could I promise him that?”

“One does,” said the man, answering. She shook away the blur and saw that it was Dr. Otis. “I promised him the same thing myself. One just. . . does,” he shrugged. “Heri Gonza promises them, too.”

“I saw that,” she nodded. “He seems to wonder ‘How could I?’ too.”

“He does what he can,” said the doctor, indicating, with a motion of his head, the special hospital wing in which they stood, the row of doors behind and beyond, doors to laboratories, doors to research and computer rooms, store rooms, staff rooms, all donated by the comedian. “In a way he has more right to make a promise like that than Billy’s doctor.”

“Or Billy’s sister,” she agreed tremulously. She turned to walk down the corridor, and the doctor walked with her. “Any new cases?”

“Two.”

She shuddered. “Any—”

“No,” he said quickly, “no deaths.” And as if to change the subject, he said, “I understand you’re to be congratulated.”

“What? Oh,” she said, wrenching her mind away from the image of Billy’s face, half marble, half mobile mahogany. “Oh, the award. Yes, they called me this afternoon. Thank you. Somehow it. . . doesn’t mean very much right now.”

They stood before his office at the head of the corridor. “I think I understand how you feel,” he said. “You’d trade it in a minute for—” he nodded down the corridor toward the boy’s room.

“I’d even trade it for a reasonable hope,” she agreed. “Good night, Doctor. You’ll call me?”

“I’ll call you if anything happens. Including anything good. Don’t forget that, will you? I’d hate to have you afraid of the sound of my voice.”

“Thank you, Doctor.”

“Stay away from the trideo this once. You need some sleep.”

“Oh, Lord. Tonight’s the big effort,” she remembered.

“Stay away from it,” he said with warm severity. “You don’t need to be reminded of iapetitis, or be persuaded to help.”

“You sound like Dr. Horowitz.”

His smile clicked off. She had meant it as a mild pleasantry; if she had been less tired, less distraught, she would have had better sense. Better taste. Horowitz’ name echoed in these of all halls like a blasphemy. Once honored as among the greatest of medical researchers, he had inexplicably turned his back on Heri Gonza and his Foundation, had flatly refused research grants, and had publicly insulted the comedian and his great philanthropy. As a result he had lost his reappointment to the directorship of the Research Institute and a good deal of his professional standing. And like the sullen buffoon he was, he plunged into research— ”real research,” he inexcusably called it—on iapetitis, attempting single-handedly not only to duplicate the work of the Foundation, but to surpass it: “the only way I know,” he had told a reporter, “to pull the pasture out from under that clod and his trained sheep.” Heri Gonza’s reply was typical: by deft sketches on his programs, he turned Horowitz into an improper noun, defining a horowitz as a sort of sad sack or poor soul, pathetic, mildly despicable, incompetent and always funny—the kind of subhuman who not only asks for, but justly deserves, a pie in the face. He backed this up with a widely publicized standing offer to Dr. Horowitz of a no-strings-attached research grant of half a million; which Dr. Horowitz, after his first unprintable refusal (his instructions to the comedian as to what he could do with the money were preceded by the suggestion that he first change it into pennies), ignored.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.