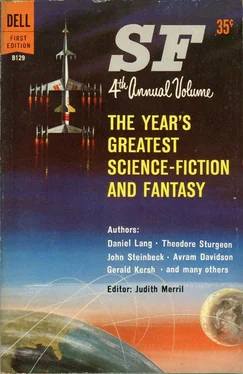

Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1959, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1959

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Therefore the remark, even by a Nobel prizewinner, even by a reasonably handsome woman understandably weary and upset, even by one whose young brother lay helpless in the disfiguring grip of an incurable disease—such a remark could hardly be forgiven, especially when made to the head of the Iapetitis Wing of the Medical Center and local chairman of the Foundation. “I’m sorry, Dr. Otis,” she said. “I . . . probably need sleep more than I realized.”

“You probably do, Dr. Barran,” he said evenly, and went into his office and closed the door.

“Damn,” said Iris Barran, and went home.

No one knew precisely how Heri Gonza had run across the idea of an endurance contest cum public solicitation of funds, or when he decided to include it in his bag of tricks. He did not invent the idea; it was a phenomenon of early broadcasting, which erupted briefly on the marriage of video with audio in a primitive device known as television. The performances, consisting of up to forty continuous hours of entertainment interspersed with pleas for aid in one charity or another, were headed by a single celebrity who acted as master of ceremonies and beggar-in-chief. The terminologically bastardized name for this production was telethon, from the Greek root tele, to carry, and the syllable thon, meaningless in itself but actually the last syllable of the word marathon. The telethon, sensational at first, had rapidly deteriorated, due to its use by numbers of greedy publicists who, for the price of a phone call, could get large helpings of publicity by pledging donations which, in many cases, they failed to make, and the large percentage of the citizenry whose impulse to give did not survive their telephoned promises. And besides, the novelty passed, the public no longer watched. So for nearly eighty years there were no telethons, and if there had been, a disease to hang one on would have been hard to find. Heart disease, cancer, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy—these, and certain other infirmities on which public appeals had been based, had long since disappeared or were negligibly present. Now, however, there was iapetitis.

A disorder of the midbrain and central nervous system, it attacked children between the ages of three and seven, affecting only one hemisphere, with no statistical preference for either side. Its mental effects were slight (which in its way was one of the most tragic aspects of the disease), being limited to aphasia and sometimes a partial alexia. It had more drastic effects on the motor system, however, and on the entire cellular regeneration mechanisms of the affected side, which would gradually solidify and become inert, immobile. The most spectacular symptom was on the superficial pigmentation. The immobilized side turned white as bleached bone, the other increasingly dark, beginning with a reddening and slowly going through the red-browns to a chocolate in the later stages. The division was exactly on the median line, and the bicoloration proceeded the same way in all cases, regardless of the original pigmentation.

There was no known cure.

There was no known treatment.

There was only the Foundation—Heri Gonza’s Foundation—and all it could do was install expensive equipment and expensive people to operate it . . . and hope. There was nothing anyone else could do which would not merely duplicate Foundation efforts and, besides, with one exception the Foundation already had the top people in microbiology, neurology, virology, internal medicine, and virtually every other discipline which might have some bearing on the disease. There were, so far, only 376 known cases, every one of which was in a Foundation hospital.

Heri Gonza had been associated with the disease since the very beginning, when he visited a children’s hospital and saw the appalling appearance of the first case, little Linda Tresak of Arkansas. When four more cases appeared in the Arkansas State Hospital after she was a patient there for some months, Heri Gonza moved with characteristic noise and velocity. Within forty-eight hours of his first knowledge of the new cases, all five were ensconced in a specially vacated wing of the Medical Center, and mobilization plans were distributed to centers all over the world, so that new clinics could be set up and duplicate facilities installed the instant the disease showed up. There were at present forty-two such clinics. Each child had been picked up within hours of the first appearance of symptoms, whisked to the hospital, pampered, petted, and . . . observed. No treatment. No cure. The white got whiter, the dark got darker, the white side slowly immobilized, the dark side grew darker but was otherwise unaffected; the speech difficulty grew steadily (but extremely slowly) worse; the prognosis was always negative. Negative by extrapolation: any organism in the throes of such deterioration might survive for a long time, but must ultimately succumb.

In a peaceful world, with economy stabilized, population growing but not running wild any longer, iapetitis was big news. The biggest.

The telethon was, unlike its forbears, not aimed at the public pocket. It was to serve rather as a whip to an already aware world, information to the informed, aimed at earlier and earlier discovery and diagnosis. It was one of the few directions left to medical research. The disease was obviously contagious, but its transmission method was unknown. Some child, somewhere, might be found early enough to display some signs of the point of entry of the disease, something like a fleabite in spotted fever, the mosquito puncture in malaria—some sign which might heal or disappear soon after its occurrence. A faint hope, but it was a hope, and there was little enough of that around.

So, before a wide gray backdrop bearing a forty-foot insigne in the center, the head and shoulders of a crying child vividly done in half silver, half mahogany, Heri Gonza opened his telethon.

Iris Barran got home well after it had started; she had rather overstayed her hospital visit. She came in wearily and slumped on the divan, thinking detachedly of Billy, thinking of Dr. Otis. The thought of the doctor reminded her of her affront to him, and she felt a flash of annoyance, first at herself for having done it, and immediately another directed at him for being so touchy—and so unforgiving. At the same time she recalled his advice to get some sleep, not to watch the telethon; and in a sudden, almost childish burst of rebellion she slapped the arm of the divan and brought the trideo to life.

The opposite wall of the room, twelve feet high, thirty feet long, seemed to turn to smoke, which cleared to reveal an apparent extension of the floor of the room, back and (farther back, to Heri Gonza’s great gray backdrop. All around were the sounds, the smells, the pressure of the presence of thousands of massed, rapt people. “. . . so I looked down and there the horse had caught its silly hoof in my silly stirrup. ‘Horse,’ I says, ‘if you’re gettin’ on, I’m gettin’ off!’”

The laugh was a great soft booming explosion, as usual out of all proportion to the quality of the witticism. Heri Gonza had that rarest of comic skills, the ability to pyramid his effects, so that the mildest of them seemed much funnier than it really was. It was mounted on a rapidly stacked structure of previous quips and jokes, each with its little store of merriment and all merriment suppressed by the audience for fear of missing not only the next joke, but the entire continuity. When the pyramid was capped, the release was explosive. And yet in that split instant between capper and explosion, he always managed to slip in a clear three or four syllables. “On my way here—” or “When the president—” or “Like the horowitz who—” which, repeated and completed after the big laugh, turned out to be the base brick for the next pyramid.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.