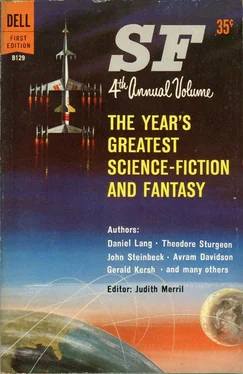

Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1959, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1959

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“He has,” said the girl, company-polite as always, but now utterly cold. Anyone who knew that creature to speak to . . . “Your name, please?”

Iris told her, and added, “Please tell him it’s very important.”

The cave went dark but for the slowly rotating symbol of the phone company, indicating that the operator was doing her job. Then a man’s head appeared and looked her over for a moment, and then said, “Dr. Barran?”

“Dr. Horowitz.”

She had not been aware of having formed any idea of the famous (infamous?) Horowitz; yet she must have. His face seemed too gentle to have issued those harsh rejoinders which the news attributed to him; yet perhaps it was gentle enough to be taken for the fumbler, the fool so many people thought he was. His eyes, in some inexplicable way, assured her that his could not be clumsy hands. He wore old-fashioned exterior spectacles; he was losing his hair; he was younger than she had thought, and he was ugly. Crags are ugly, tree-trunks, the hawk’s pounce, the bear’s foot, if beauty to you is all straight lines and silk. Iris Barran was not repulsed by this kind of ugliness. She said bluntly, “Are you doing any good with the disease?” She did not specify: today, there was only one disease.

He said, in an odd way as if he had known her for a long time and could judge how much she would understand, “I have it all from the top down to the middle, and from the bottom up to about a third. In between—nothing, and no way to get anything.”

“Can you go any further?”

“I don’t know,” he said candidly. “I can go on trying to find ways to go further, and if I find a way, I can try to move along on it.”

“Would some money help?”

“It depends on whose it is.”

“Mine.”

He did not speak, but tilted his head a little to one side and looked at her.

She said, “I won ... I have some money coming in. A good deal of it.”

“I heard,” he said, and smiled. He seemed to have very strong teeth, not white, not even, just spotless and perfect “It’s a good deal out of my field, your theoretical physics, and I don’t understand it. I’m glad you got it. I really am. You earned it.”

She shook her head, denying it, and said, “I was surprised.”

“You shouldn’t have been. After ninety years of rather frightening confusion, you’ve restored the concept of parity to science—” he chuckled—”though hardly in the way anyone anticipated.”

She had not known that this was her accomplishment; she had never thought of it in those terms. Her demonstration of gravitic flux was a subtle matter to be communicated with wordless symbols, quite past speech. Even to herself she had never made a conversational analogue of it; this man had, though, not only easily, but quite accurately.

She thought, if this isn’t his field, and he grasps it like that—just how good must he be in his own? She said, “Can you use the money? Will it help?”

“God,” he said devoutly, “can I use it. . . . As to whether it will help, Doctor, I can’t answer that. It would help me go on. It may not make me arrive. Why did you think of me?”

Would it hurt him to know? she asked herself, and answered, it would hurt him if I were not honest. She said, “I offered it—to the Foundation. They wouldn’t touch it. I don’t know why.”

“I do,” he said, and instantly held up his hand. “Not now,” he said, checking her question. He reached somewhere off-transmission and came up with a card, on which was lettered, AUDIO TAPPED.

“Who—”

“The world,” he overrode her, “is full of clever amateurs. Tell me, why are you willing to make such a sacrifice?”

“Oh—the money. It isn’t a sacrifice. I have enough: I don’t need it. And—my baby brother. He has it.”

“I didn’t know,” he said, with compassion. He made a motion with his hands. She did not understand. “What?”

He shook his head, touched his lips, and repeated the motion, beckoning, at himself and the room behind him. Oh. Come where I am.

She nodded, but said only, “It’s been a great pleasure talking with you. Perhaps I’ll see you soon.”

He turned over his card; obviously he had used it many times before. It was a map of a section of the city. She recognized it readily, followed his pointing finger, and nodded eagerly. He said, “I hope it is soon.”

She nodded again and rose, to indicate that she was on her way. He smiled and waved off.

It was like a deserted city, or a decimated one; almost everyone was off the streets, watching the telethon. The few people who were about all hurried, as if they were out against their wills and anxious to get back and miss as little as possible. It was known that he intended to go on for at least thirty-six hours, and still they didn’t want to miss a minute of him. Wonderful, wonderful, she thought, amazed (not for the first time) at people—just people. Someone had once told her that she was in mathematics because she was so apart from, amazed at, people. It was possible. She was, she knew, very unskilled with people, and she preferred the company of mathematics, which tried so hard to be reasonable, and to say what was really meant. . . .

She easily found the sporting-goods store he had pointed out on his map, and stepped into the darkened entrance. She looked carefully around and saw no one, then tried the door. It was locked, and she experienced a flash of disappointment of an intensity that surprised her. But even as she felt it, she heard a faint click, tried the door again, and felt it open. She slid inside and closed it, and was gratified to hear it lock again behind her.

Straight ahead a dim, concealed light flickered, enough to show her that there was a clear aisle straight back through the store. When she was almost to the rear wall, the light flickered again, to show her a door at her right, deep in an ell. It clicked as she approached, and opened without trouble. She mounted two flights of stairs, and on the top landing stood Horowitz, his hands out. She took them gladly, and for a wordless moment they stood like that, laughing silently, until he released one of her hands and drew her into his place. He closed the door carefully and then turned and leaned against it.

“Well!” he said. “I’m sorry about the cloak and dagger business.”

“It was very exciting.” She smiled. “Quite like a mystery story.”

“Come in, sit down,” he said, leading the way. “You’ll have to excuse the place. I have to do my own housekeeping, and I just don’t.” He took a test-tube rack and a cracked bunsen tube from an easy chair and nodded her into it. He had to make two circuits of the room before he found somewhere to put them down. “Price of fame,” he said sardonically, and sat down on a rope-tied stack of papers bearing the flapping label Proceedings of the Pan-American Microbiological Society. “Where that clown makes a joke of Horowitz, other fashionable people make a game of Horowitz. A challenge. Track down Horowitz. Well, if they did, through tapping my phone or following me home, that would satisfy them. Then I would be another kind of challenge. Bother Horowitz. Break in and stir up his lab with a stick. You know.”

She shuddered. “People are . . . are so . . .”

“Don’t say that, whatever it was,” said Horowitz. “We’re living in a quiet time, Doctor, and we haven’t evolved too far away from our hunting and tracking appetites. It probably hasn’t occurred to you that your kind of math and my kind of biology are hunting and tracking too. Cut away our science bump and we’d probably hunt with the pack too. A big talent is only a means of hunting alone. A little skill is a means of hunting alone some of the time.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.