But how long have we been prepared to see this? Did we not have to work our way (with pleasure) through Gernsback and “scientifiction” to Campbell’s then-revolutionary 1938-1942 magazines, and then from E. E. Smith to Heinlein, Leiber, and Asimov—and again, to Boucher’s revolutionary notion that a science-fantasy magazine could be well-written —to Bester, Miller, Budrys, Cordwainer Smith—before we were ready for either Cat’s Cradle or “Terminal Beach?”

* * * *

Or if Borges had been translated as he wrote, if the eight stories in Ficciones (Fictions) had been available in 1941, instead of 1962 . . .

I remember vividly the excitement of discovering The Star Maker and Odd John in the early ‘40s; Stapledon opened tantalizing and terrifying vistas of probability for me. For others, it may have been C. S. Lewis, or M. P. Shiel, or E. R. Eddison; but there is no question that the impact of these powerful imaginative thinkers on a whole generation of writers was one of the major forces that moved s-f out of the technocratic-primitivism of “scientifiction” to the sociological-sci-fi of the “great days” of Astounding and Unknown, and further, to the psychological/semantic/psychiatric science-fantasy of the early years of Galaxy and Fantasy and Science Fiction.

But that was as far as the impetus of that group of brilliant apologists of dualism could take us. The next step we had to reach—are only now reaching—essentially by bootstrap-climbing. So it seems cruelly ironic now to discover that our newest concepts, painfully evolved over a quarter century of speculative interchange from the combined traditions of magic and mathematics, physics and poetry, were already set down—in essays, stories, poems, allegories, sometimes unabashed plot outlines—before we were fairly started on the process, by one man drawing on the whole range of aesthetic/intellectual traditions that have since filtered through to us, from a dozen different sources.

Would we have arrived any sooner, or any saner, at the crossroads of communication where we now stand—where poet and pragmatist, scientist and surrealist, are equally frequently disconcerted to see themselves mirrored in each other’s eyes—would we have come to this gathering place, the converging of the many roads toward “reality” traveled by twentieth-century thought, any more readily for the guidance of one brilliant mind far ahead?

Or did we have to get this far ourselves before we could make out the meaning of the light? Did Borges’ work, and Jarry’s, simply have to wait for the rest of us to catch up? Perhaps we had to go the Zen route before we could contemplate the statement, “ ‘Pataphysics is the science ...” with equanimity (let alone delight), and wail for our learned Academies to convene Conferences on the nature of time before Borges’ “Tlon Uqbar, Tertius Orbis” became comprehensible?

Perhaps we did. Perhaps each cultural island—whether a nation, genre, discipline, or single man—must grow its own way through the stages of naive rationalism and hardware sophistication, before it can approach the recognition of the inalienable association between the concurrent-and-diverse “realities” of physics and metaphysics, mathematics and mysticism, psyche and soma, science and art.

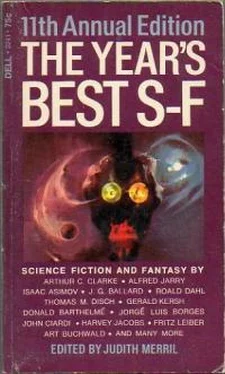

Judith Merril

Milford, 1966