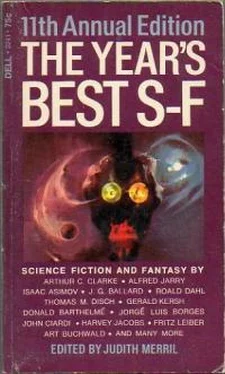

The Year's Best Science Fiction 11

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1967, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Best Science Fiction 11

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1967

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Best Science Fiction 11: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Best Science Fiction 11 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I mention these titles in particular because they are neither whimsical fantasies, space-cowboy adventures, sex-and-sci-fi spoofs, nor sprightly satires, but serious speculative fiction of a kind that actually had no market here a few years ago (bar he infrequent F&SF acceptance).

It is part of the same happy blurring of edges that Daniel Keyes’ Flowers for Algernon was issued recently by Harcourt with neither labels nor disclaimers on the jacket—and that Gold Medal’s Beaumont selection. The Magic Man, did specify “science fantasy” out front, when the earlier collections from which it was culled had avoided the tag like the plague-carrier it was known to be for a serious and talented young writer.

It almost seems that the trend is to using the label when it seems helpful, and omitting it when it does not. One hesitates to make any assumption of such widespread sanity, but the magazine situation almost requires it. Some readers, and most writers, will already have noticed that this Annual contains no Honorable Mentions listing. For the last two or three years, the attempt to compile such a list has been increasingly frustrating. The diffusion is too great: Even if it were within my powers to be certain I have seen everything entitled to consideration in a given year, I no longer know where to draw the line.

I use poetry, and sometimes cartoons, and frequently newspaper pieces among the selections: Ought they to be covered in the Mentions too? What about British publications, and English-language books published in other countries? How about things like the Christian Science Monitor’s “Martian papers,” describing the amusement along’ the Canal at UFO-nuts who claim to have seen six-foot-lall metallic-dothed extraterrestrials? Or the deadpan stuff the Realist has begun to use (since they broke the s-f ice with Harvey Bilker’s “Genetic Faux Pas”)? How in the world do you decide on a listing for (almost anything from) Roger Price’s inflammatory Grump? What about Fernando Krahn’s cartoons in the Reporter ? How about poetry? Or critical writing?

The answer, of course, was to mention all these other things in the Summation, which began to make the addition of the HM list not only burdensome to me and unfair to authors whose work I would not discover till two months, or two years, later, but foolish as well, since much of the highest-quality work was mentioned only off-list. The new answer is to omit any pretense at publication of a comprehensive listing. Most of the items of special merit I noticed during the year have already been mentioned in the story notes) there are a few others I feel should not be entirely passed by— most importantly, some new names from the 1965 magazines:

From Amazing and Fantastic —Stanley E. Aspiltle, Jr., John Douglas, Alfred Grossman, Judith E. Schrier.

From If —John McCallum, D. M. Melton, Laurence S. Todd.

From Analog —Michael Karageorge, Laurence A. Perkins.

From F&SF —John Thomas Richards.

There were also some stories of special interest by established authors, which did not, one way or another, get mentioned inside: Miriam Allen de Ford’s “The Expendables,” Chad Oliver’s “End of the Line,” Edgar Pangborn’s “Wogglebeast,” all from F&SF; William F. Temple’s “The Legend of Ernie Deacon” and James H. Schmitz’s “The Pork Chop Tree,” from Analog; Lloyd Biggie, Jr.’s “Pariah Planet” and Theodore L. Thomas’ “Manfire,” from Worlds of Tomorrow, Gerald Pearce’s “Security Syndrome,” from If, and Richard Wilson’s “Harry Protagonist, Brain-Drainer,” from Galax/; “Don’t Touch Me, I’m Sensitive,” by James Stamers, in Gamma; “The Casting Couch,” by Lewis Kovner, in Rogue; Florence Engel Randall’s “The Watchers,” in Harper’s; and stories from all over by Frank Herbert: “Committee of the Whole” (Galaxy), “The GM Effect” (Analog), “Greenslaves” (Amazing).

And there was Boris Vian’s “The Dead Fish,” outstanding among a collection of good stories in the anthology edited and translated by Damon Knight, 13 French Science Fiction Stories (Bantam).

Nor have I mentioned Cordwainer Smith’s Space Lords collection, memorable not only for the stories, but for the author’s instructive and revealing prologue, in which he explains, in part, just what it is that is different about Smith stories. Required reading for would-be s-f writers (and for many who already are)—as is Brian Aldiss’ long, thoughtful analysis of three British writers in SF Horizons No. 2.

And there are some other British writers, not all new-in-1965, but names still unfamiliar here, which I suspect will not be so for long: William Barclay, John Baxter, Daphne Castell, Robert Cheetham, Jael Cracken, John Hamilton, David Harvey, R. W. Mackleworth, Dikk Richardson, David Newton, Bob Parkinson, E. C. Williams.

One way and another, I keep coming back to it. The important things happening in American s-f are not happening in it at all. We have writers comparable to Ballard in stature, for instance—but not in current achievement, and certainly not in influence within the field. Cordwainer Smith and Theodore Sturgeon have each published two new stories in the last eighteen months or so—and none of them close to the authors’ best work. Leiber has been productive: a Tarzan novelization, and thousands of words of magazine stories, some of them very good reading, all rather closer in period to Tarzan than to Leiber’s own work of a few years back (“Mariana,” “A Deskfui of Girls,” “The Secret Songs,” “The Silver Eggheads,” The Wanderer). Nothing at all from Alfred Bester for three years now, nor from Walter Miller for much, much longer. Kurt Vonnegut continues to do a novel every year or two that almost makes up for the rest of what’s missing—but he is not in the same sense a part of the field here at all; his impact on other American writers is almost more from “outside” than Ballard’s.

The novel generally acclaimed as the best American product last year was Frank Herbert’s Dune—a long, and in part excellent, but completely conventional future-historical, admirable essentially for its complexity rather than for any original or speculative contribution. Certainly there is nothing in it to stimulate or influence the work of others.

As it happens, the stimulus is being provided from outside—and not just from England. It is coming from exciting new work in psychology and the allied sciences; from the avant-gardistes and poets who have begun using the images and contexts of s-f with or without concern for the sources; and from the impact of the belated translation and publication of people like Borges and Jarry.

It is interesting to speculate on what the difference in our thinking and writing might have been, if we had had Jarry as part of the s-f tradition, along with Verne and Wells. Jarry himself was reading these men as they wrote: Verne in his childhood. Wells in his prime. He responded to Wells (See “How to Construct a Time Machine” in the Selected Works), but also with Wells, to the scientific discoveries of the turn of the century. In a sense, he is Jules Verne’s left hand, as Wells might be the right.

But if we had had Jarry, would we have read him? From today’s vantage point, a hectic half century of scientific revolutions and upheavals later, Jarry’s responses are rather more in keeping with the direction of physics itself than were Wells’ marvelously sane and rational civilized adductions.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.