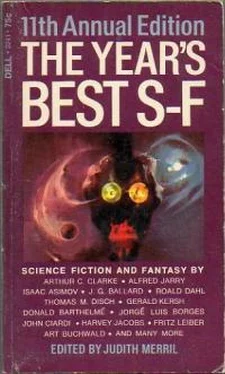

The Year's Best Science Fiction 11

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1967, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Best Science Fiction 11

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1967

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Best Science Fiction 11: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Best Science Fiction 11 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Oh.”

“It looks solid, doesn’t it?”

“Well, yeah, but that could just be an optical illusion.”

“Do you think we ought to chance revving her up to full power and going ahead?”

“Well, I don’t know sir. Maybe one of us better get out and have a close look at the thing. It could be just a cloud of dust particles that .. .”

“Can we pull in any closer?”

“Maybe. If it is solid, then it may have some gravity of its own. Then it would just pull us right smack into it.”

“Are you a religious man, Johnny?”

“No ... I, uh ... well, how do you mean?”

“I mean like believing that this is the wall that separates heaven from the rest of the universe. Do you think there is a heaven?”

“I guess there’s a heaven. But I never thought . . .”

“We could even be dead right now. Like, you know, maybe we crashed into an asteroid or something. Maybe we’re dead, and now we’ve reached heaven.”

“I don’t feel like I’m dead. Wouldn’t we have remembered it if we had crashed?”

“Yeah, I guess so. One of us is going to have to go out there and have a look.”

“I’ll go, Frank.”

“No you won’t. The Space Administration needs men like you. I’ll go.”

“But Frank, what if . . .”

“Aw, come on! All this upset over nothing! Let’s behave like a couple of men.”

“Okay. You’re right. Can I help you put on your suit?”

“Yeah. Meet me in the pressure room.”

Ours was one of the two-man jobs, used only for charting. One of us sat at either end. He flew, and I drew. The pressure room was right in the middle of the ship. I helped the captain put on his suit, and then went back to watch him on the television monitor.

“How is it out there, Frank?”

“I’m fine. I’m almost there. I think I can see the ... the . J . well, I’ll be damned!”

“Is something the matter? Frank?”

He was right up against the wall. It was solid all right. I could see him hunched over in one little spot.

“Johnny?”

“Yes sir?”

“Have you got a quarter?”

“A ... a what?”

“A quarter. Twenty-five cents.”

“Well, I don’t know, sir. What do you need a quarter for?”

“You find me one. I’m coming back for it.”

There was some money in the ship. I don’t know why, but for some reason, somebody had known to have some money on board. When the captain got back, I gave him the money.

“Why do you want a quarter, Frank?”

“You’d better get one for yourself, too. And start getting your suit on. I’ll be right back.”

He took the quarter and left. And he came right back. But there was something wrong. His eyes were all glassy, and his mouth just hung loosely at the jaw. His eyebrows were turned up, and his forehead was all wrinkled.

“What is it, Frank? What’s the matter?”

“It was nothing. Really. It was nothing.”

When I got about twenty feet away from the wall, I could see them. There were hundreds of them, plastered all over it. Old signs. There was an “Eat At Joe’s,” and a great big “Kilroy was here,” and hearts with names in them. As I got closer, I could even see the hand-scrawled four-letter words with crude drawings.

As I got right up against the wall, I noticed the little white square sign. It said,

obviously you are not convinced that this is the end of the universe. if you will place a quarter in the slot below, the peep-hole will open, and you can see for yourself.

And the captain was right. I paid my quarter and looked through the peep-hole. But it was nothing.

SUMMATION

Burroughs would have been lost . . . Edgar Rice Burroughs, that is. Since the days of his novel The Warlord of Mars things have changed in outer space. Yet William Burroughs, he of Naked Lunch and Nova Express fame, would have loved nearly every minute of it.

At ten o’clock on Sunday morning, when the decent folk of London were still in their beds, delegates to the 23rd World Science Fiction Convention in London were discussing “The Robot in the Executive Suite,” speculating on practical optimums for robot construction.

Only one lonely bug-eyed monster appeared at the convention— at the costume ball/ and Penguin Books had great difficulty in persuading a Dalek [ Unautomated, man-sized U.K. version of Robbie the Robot— controls, mike, etc., are inside, as is operator. ] to appear. Monsters and Martians get harder to find every day. Science fiction, since the good old days when Hugo Gernsback first named the genre “Scientifiction” and printed space operatics in pulp magazines, has come of a respectable age. Unlikely Martians are of less interest than what one British writer, J. G. Ballard, has called “inner space,” a very real world. In the space age Jules Verne can’t shine a candlepower before the reality of Gemini.

This was the opening of the Spectator’s report on the World Science Fiction Convention in London last August. The London Sunday Times Magazine, shortly afterward, came out with a special s-f section: an article on the Clarke-Kubrick movie, one on the BBC’s (then) forthcoming s-f drama series, and a thoughtful profile of John W. Campbell, editor of Analog, which summed up:

. . . Life to Campbell is a gigantic experiment in form, and earth the forcing-house —an impeccable vision, but one not warmed (in his theories, that is) by a feeling for the pain or personal potential of the individuals in the experiment. That kind of gentleness in expression seemed to disappear with Don A. Stuart.

So that, ironically, as s-f becomes increasingly respectable, John Campbell, its acknowledged father-figure, can’t really claim his throne. He provides the continuity, he shaped much of the thought, he made many reputations. S-f narrowed from the vastness of space to the greater complexity of “sociological” s-f with him presiding. But now it is narrowing towards the highly focused, upside-down detail of “innerspace.” The tone is personal and subjective, the quality of expression important. . . . There is even a literary magazine: SF Horizons. None of this is Campbell’s style.

You may disagree with the views of either or both reporters (Bill Butler in the Spectator, Pal Williams in the Times Magazine). What is significant is that they had views, and expressed them intelligently; that neither one approached the job in the role of literary slummer, or even intrepid anthropologist among the fantasists, but simply and seriously as observers reporting on a field they knew and understood, and believed to be of interest to other readers.

I was about to say, it couldn’t happen here—but I suspect the difference in attitude is not so much spatial as temporal. What has already happened there is just beginning to happen here.

Which is to say: the big news in s-f this year is mostly not in s-f—not this side of the ocean. (Exceptions: the establishment of the SFWA; and Doubleday’s expanded publishing schedule, under the supervision of Lawrence P. Ashmead, who looks to be the best thing that has happened to s-f book publishing here in a long time.)

In a sense, the biggest news of the year is that it is harder than ever to locate on the literary map any reliable boundary line between s-f and anything else. The other side of the coin, whose tail is the lack of focus and esprit in the specialty field here, is, I suppose, the diminishment of spirited opposition or snobbism directed at the field. To some extent, this is a self-reproducing cycle; to a greater degree, the changing faces on both sides are being shaped by pressures initiating entirely outside the local literary scene, particularly such adjacent areas as education, advertising, psychology, and the Think Factory phenomenon. The s-f label becomes ludicrous, not to say invisible, when advertisements like the star-sprinkled page with the cute little capsule through whose wide-vision window a cheery astronaut and his mouth organ illustrate the pitch: “Three billion people will look up to you ... on Dec. 16, 1965, the Hohner Harmonica became the first musical instrument to be played in outer space,” appear in the same sort of magazines which now publish such stories as “Game,” “Somewhere Not far from Here,” “The Girl Who Drew the Gods,” “The Drowned Giant” (and Stanley Elkin’s “Perlmutter at the East Pole” in the Post), with neither apologies, explanations, nor exclamation points.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Best Science Fiction 11» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.