“You’ve come home,” he said.

“So I have,” said she.

“I fought all night,” she added, “with the Old Man of the Mountain,” for you must know that this demon is a legend in Ourdh; he is the god of this world who dwells in a cave containing the whole world in little, and from his cave he rules the fates of men.

“Who won?” said her husband, laughing, for in the sunrise when everything is suffused with fight it is difficult to see the seriousness of injuries.

“I did!” said she. “The man is dead.” She smiled, splitting open the wound on her cheek, which began to bleed afresh. “He died,” she said, “for two reasons only: because he was a fool. And because we are not.”

And all the birds in the courtyard broke out shouting at once.

Like the late Harold Ross of The New Yorker and most other editors, I am reluctant to print any story I don’t understand. “The Changeling” appears here, nevertheless.

In my book of critical essays, In Search of Wonder, I made a distinction between stories that make sense and those that mean something. I am unable to “make sense” out of this one—to make it add up neatly and come out even—but I strongly feel that it means something, just as Kafka’s The Trial or Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” does.

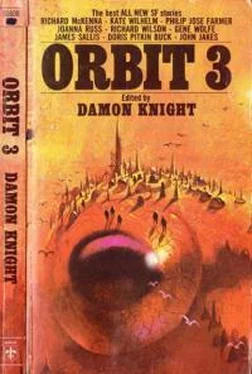

This haunting story is Gene Wolfe’s second for Orbit; his first was “Trip, Trap,” in Orbit 2.

The Changeling

by Gene Wolfe

I suppose whoever finds these papers will be amazed at the simplicity of their author, who put them under a stone instead of into a mailbox or a filing cabinet or even a cornerstone—these being the places where most think it wise to store up their writings. But consider, is it not wiser to put papers like these into the gut of a dry cave as I have done?

For if a building is all it should be, the future will spare it for a shrine; and if your children’s sons think it not worth keeping, will they think the letters of the builders worth reading? Yet that would be a surer way than a filing cabinet. Answer truly: Did you ever know of papers to be read again once they entered one of these, save when some clerk drew them out by number? And who would seek for these?

There is a great, stone-beaked, hook-billed snapping turtle living under the bank here, and in the spring, when the waterfowl have nested and brooded, he swims beneath their chicks more softly than any shadow. Sometimes they peep once when he takes their legs, and so they have more of life than these sheets would have once the clacking cast iron jaw of a mailbox closed on them.

Have you ever noted how eager it is to close when you have pulled out your hand? You cannot write The Future on the outside of an envelope; the box would cross that out and stamp Dead Letter Office in its place.

Still, I have a tale to tell; and a tale untold is one sort of crime:

I was in the army, serving in Korea, when my father died. That was before the North invaded, and I was supposed to be helping a captain teach demolition to the ROK soldiers. The army gave me compassionate leave when the hospital in Buffalo sent a telegram saying how sick he was. I suppose everyone moved as fast as they could, I know I did, but he died while I was flying across the Pacific. I looked into his coffin where the blue silk lining came up to his hard, brown cheeks and crowded his working shoulders; and went back to Korea. He was the last family I had, and things changed for me then.

There isn’t much use in my making a long story of what happened afterward; you can read it all in the court-martial proceedings. I was one of the ones who stayed behind m China, neither the first nor the last to change his mind a second time and come home. I was also one of the ones who had to stand trial; let’s say that some of the men who had been in the prison camp with me remembered things differently. You don’t have to like it.

While I was in Ft. Leavenworth I started thinking about how it was before my mother died, how my father could bend a big nail with his fingers when we lived in Cassonsville and I went to the Immaculate Conception School five days a week. We left the month before I was supposed to start the fifth grade, I think.

When I got out I decided to go back there and look around before I tried to get a job. I had four hundred dollars I had put in Soldier’s Deposit before the war, and I knew a lot about living cheap. You learn that in China.

I wanted to see if the Kanakessee River still looked as smooth as it used to, and if the kids I had played softball with had married each other, and what they were like now. Somehow the old part of my life seemed to have broken away, and I wanted to go back and look at that piece. There was a fat boy who was tongue-tied and laughed at everything, but I had forgotten his name. I remembered our pitcher, Ernie Cotha, who was in my grade at school and had buck teeth and freckles; his sister played center field for us when we couldn’t get anybody else, and closed her eyes until the ball thumped the ground in front of her. Peter Palmieri always wanted to play Vikings or something like that, and pretty often made the rest of us want to too. His big sister Maria bossed and mothered us all from the towering dignity of thirteen. Somewhere in the background another Palmieri, a baby brother named Paul, followed us around watching everything we did with big, brown eyes. He must have been about four then; he never talked, but we thought he was an awful pest.

I was lucky in my rides and moved out of Kansas pretty well. After a couple of days I figured I would be spending the next night in Cassonsville, but it seemed as though I had run out of welcomes outside a little hamburger joint where the state route branched off the federal highway. I had been holding out my thumb nearly three hours before a guy in an old Ford station wagon offered me a lift. I’d mumbled, “Thanks,” and tossed my AWOL bag in back before I ever got a good look at him. It was Ernie Cotha, and I knew him right away—even though a dentist had done something to his teeth so they didn’t push his lip out any more. I had a little fun with him before he got me placed, and then we got into a regular school reunion mood talking about the old times.

I remember we passed a little barefoot kid standing alongside the road, and Ernie said, “You recollect how Paul always got in the way, and one time we rubbed his hair with a cow pile? You told me next day how you caught blazes from Mama Palmieri about it.”

I’d forgotten, but it all came back as soon as he mentioned it. “You know,” I said, “it was a shame the way we treated that boy. He thought we were big shots, and we made him suffer for it.”

“It didn’t hurt him any,” Ernie said. “Wait till you see him; I bet he could lick us both.”

“The family still live in town?”

“Oh sure.” Ernie let the car drift off the blacktop a little, and it threw up a spurt of dust and gravel before he got it back on. “Nobody leaves Cassonsville.” He took his eyes from the road for a moment to look at me. “You knew Maria’s old Doc Witte’s nurse now? And the old people have a little motel on the edge of the fairgrounds. You want me to drop you there, Pete?”

I asked him how the rates were, and he said they were low enough, so, since I’d have to bunk down somewhere, I told him that would be all right. We were quiet then for five or six miles, before Ernie started up again.

“Say, you remember the big fight you two had? Down by the river. You wanted to tie a rock to a frog and throw him in, and Maria wouldn’t let you. That was a real scrap.”

“It wasn’t Maria,” I told him, “that was Peter.”

Читать дальше