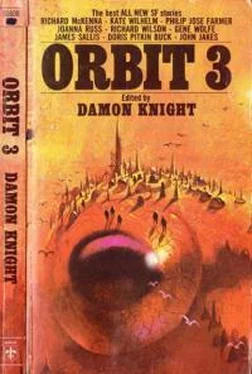

ORBIT 3

Edited by DAMON KNIGHT

A BERKLEY MEDALLION BOOK published by BERKLEY PUBLISHING CORPORATION

Copyright © 1968 by Damon Knight

All rights reserved

Published by arrangement with the author's agent

Originally published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons

The illustrations for “Bramble Bush” are by Jack Gaughan.

BERKLEY MEDALLION EDITION, SEPTEMBER, 1968

BERKLEY MEDALLION BOOKS are published by

Berkley Publishing Corporation

200 Madison Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10016

BERKLEY MEDALLION BOOKS ® TM 757,375

Printed in the United States of America

Science fiction writers sometimes seem to be engaged in a witty but very leisurely debate, in which decades may pass between one comment and the next. Thus Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s The Last Man (1826) was followed in turn by M. P. Shiel’s The Purple Cloud (1929), Alfred Bester’s “Adam and No Eve” (1941), Fredric Brown’s “Knock” (1948), and my own “Not With a Bang” (1950), among others.

Each of these writers probably felt he had said the last word; I know I did. But again and again, when a theme like this appears to be exhausted, along comes another writer who picks it up and turns it by some magic into a fresh, new thing.

Richard Wilson’s “Mother to the World” is not just a new variation on the Last Man theme; he has given it one new twist, which I will not mention, since he reveals it himself in the first three hundred words, but it’s a rather unimportant technicality anyhow. What is important is not the variation but what Wilson has made of it—this deeply honest, memorable and moving story.

Mother To The World

by Richard Wilson

His name was Martin Rolfe. She called him Mr. Ralph.

She was Cecelia Beamer, called Siss.

He was a vigorous, intelligent, lean and wiry forty-two, a shade under six feet tall. His hair, black, was thinning but still covered all of his head; and all his teeth were his own. His health was excellent. He’d never had a cavity or an operation and he fervently hoped he never would.

She was a slender, strong young woman of twenty-eight, five feet four. Her eyes, nose and mouth were regular and well-spaced but the combination fell short of beauty. She wore her hair, which was dark blonde, not quite brown, straight back and long in two pigtails which she braided daily, after a ritualistic hundred brushings. Her figure was better than average for her age and therefore good, but she did nothing to emphasize it. Her disposition was cheerful when she was with someone; when alone her tendency was to work hard at the job at hand, giving it her serious attention. Whatever she was doing was the most important thing in the world to her just then and she had a compulsion to do it absolutely right. She was indefatigable but she liked, almost demanded, to be praised for what she did well.

Her amusements were simple ones. She liked to talk to people but most people quickly became bored with what she had to say—she was inclined to be repetitive. Fortunately for her, she also liked to talk to animals, birds included.

She was a retarded person with the mentality of an eight-year-old.

Eight can be a delightful age. Rolfe remembered his son at eight—bright, inquiring, beginning to emerge from childhood but not so fast as to lose any of his innocent charm; a refreshing, uninhibited conversationalist with an original viewpoint on life. The boy had been a challenge to him and a constant delight. He held on to that memory, drawing sustenance from it, for her.

Young Rolfe was dead now, along with his mother and three billion other people.

Rolfe and Siss were the only ones left in all the world.

It was M.R. that had done it, he told her. Massive Retaliation; from the Other Side.

When American bombs rained down from long-range jets and rocket carriers, nobody’d known the Chinese had what they had. Nobody’d suspected it of that relatively backward country which the United States had believed it was softening up, in a brushfire war, for enforced diplomacy.

Rolfe hadn’t been aware of any speculation that Peking’s scientists were concentrating their research not on weapons but on biochemistry. Germ warfare, sure. There’d been propaganda from both sides about that, but nothing had been hinted about a biological agent, as it must have been, that could break down human cells and release the water.

“M.R.,” he told her. “Better than nerve gas or the neutron bomb.” Like those, it left the buildings and equipment intact. Unlike them, it didn’t leave any messy corpses—only the bones, which crumbled and blew away. Except the bone dust trapped inside the pathetic mounds of clothing that lay everywhere in the city.

“Are they coming over now that they beat us?”

“I’m sure they intended to. But there can’t be any of them left. They outsmarted themselves, I guess. The wind must have blown it right back at them. I don’t really know what happened, Siss. All I know is that everybody’s gone now, except you and me.”

“But the animals—”

Rolfe had found it best in trying to explain something to Siss to keep it simple, especially when he didn’t understand it himself. Just as he had learned long ago that if he didn’t know how to pronounce a word he should say it loud and confidently.

So all he told Siss was that the bad people had got hold of a terrible weapon called M.R.—she’d heard of that— and used it on the good people and that nearly everybody had died. Not the animals, though, and damned if he knew why.

“Animals don’t sin,” Siss told him.

“That’s as good an explanation as any I can think of,” he said. She was silent for a while. Then she said: “Your name—initials—are M.R., aren’t they?”

He’d never considered it before, but she was right. Martin Rolfe—Massive Retaliation. I hope she doesn’t blame everything on me, he thought. But then she spoke again. “M.R. That’s short for Mister. What I call you. Your name that I have for you. Mister Ralph.”

“Tell me again how we were saved, Mr. Ralph.”

She used the expression in an almost evangelical sense, making him uncomfortable. Rolfe was a practical man, a realist and freethinker.

“You know as well as I do, Siss,” he said. “It’s because Professor Cantwell was doing government research and because he was having a party. You certainly remember; Cantwell was your boss.”

“I know that. But you tell it so good and I like to hear it.”

“All right. Bill Cantwell was an old friend of mine from the army and when I came to New York I gave him a call at the University. It was the first time I’d talked to him in years; I had no idea he’d married again and had set up housekeeping in Manhattan.”

“And had a working girl named Siss,” she put in.

“The very same,” he agreed. Siss never referred to herself as a maid, which was what she had been. “And so when I asked Bill if he could put me up, I thought it would be in his old bachelor apartment. He said sure, just like that, and I didn’t find out till I got there, late in the evening, that he had a new wife and was having a houseparty and had invited two couples from out of town to stay over.”

“I gave my room to Mr. and Mrs. Glenn, from Columbus,” Siss said.

“And the Torquemadas, of Seville, had the regular guest room.” Whoever they were; he didn’t remember names the way she did. “So that left two displaced persons, you and me.”

“Except for the Nassers.”

The Nassers, as she pronounced it, were the two self-contained rooms in the Cantwell basement. The NASAs, or the Nasas, was what Cantwell called them because the National Aeronautics and Space Administration had given him a contract to study the behavior of human beings in a closed system.

Читать дальше