“Exactly,” Svirsky smiled. “Each time Ed trended to the left out there, I think the pre-vertebral ghost in him was seeking the geodesic.”

“I’ll be the instrument,” Gard said. “How do you calibrate me?”

“You’re already calibrated, in degrees of rationality on scales of perception and speech,” Svirsky said. “Get me two of those sticks you meant to use in playing Kohler to the Proteans.”

He took out his shoelaces and tied an eight-foot stick to each of Gard’s upper arms.

“So I steer you, Ed, when the pointer swings off optimum,” he said. “See, we play Kohler to ourselves now.”

Gard slanted leftward into the critical area. “The musclehead leading the muscleheads,” he laughed. “Here we go, people.”

He described what he saw and Svirsky held him to coherence with tugs and nudges. Very shortly Gard learned to correct for himself. He followed an erratic, looping, doubling course that still trended leftward. After the first lap around the cage Chalmers remarked that it was a spiral of opposite hand to the Protean mass-spiral.

“That’s our statistical trend,” Svirsky chuckled, “but who will write the equation for the path we actually follow?”

“We really must work up the statistical dynamics of witchcraft someday,” Chalmers laughed back. “Teach every sophomore how to unrun a spell.”

The fifth lap missed the ship’s ramp by twenty feet. McPherson was dismayed, but Chalmers laughed again.

“I always knew Finagle was a Protean,” he said. “We forgot to add his constant to the right hand vector;”

“We’ll add it now,” Svirsky said. “Ed, untie the sticks. Now imagine yourself running to the top of that ramp. Flex your muscles for each step. Experience yourself at the top looking down. Then pull the trigger and make it so. Can you do that?”

“Sure,” Gard said.

He looked up and down the ramp, pranced a little, then dashed to the top through a blur of motion. He turned, only to be knocked flat by three hurtling bodies.

“Take it easy,” Gard said, getting up. “It’s good to be home, but not that good, people.”

“We stood down there at least five minutes deciding why you were frozen like a statue up here,” Chalmers said. “Then Ike came up and froze, then Joe, and finally I came. We all got here at the exact, same instant.”

“I see. We snapped back into our own time. But Joe, how could you know we’d be out of the field up here? Is it a ship effect?”

“Another hunch, Ed. I suspected the Proteans might only project space in two directions so that the field might attenuate rapidly on the vertical.”

“Well what d’ye know!” McPherson said disgustedly.

“We could just as well have walked out on stilts. So damned simple! How stupid can you get?”

“Science can’t answer that question,” Chalmers said.

“Stations,” Gard said. “Let’s lift out, Ike.”

In subspace, on automatics, the four of them relaxed with coffee.

“Our report,” Gard said. “I propose we rig it and conclude that Proteus is not only unsuitable for settlement but of no interest to commerce, science or even art.”

“Right,” Chalmers agreed. “How could we ever tell them otherwise?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” McPherson said. “Use Joe’s line about fields. People savvy fields, all right.”

“Yes,” Chalmers said. “Fences around them. Flowers and grass. When a man’s in a field he’s got both feet on the ground.”

“Joe,” Gard broke in, “I think you knew more all along than you let on. Why didn’t you come up with that explanation sooner? Of course nobody got hurt, but you did let us all bloody our noses on that barrier.”

“Maybe I could have, Ed,” Svirsky admitted. “Maybe I even wanted to. But if I had, my brothers, it would have seemed to all of us too silly for words.”

“Not to speak of action,” Chalmers said softly.

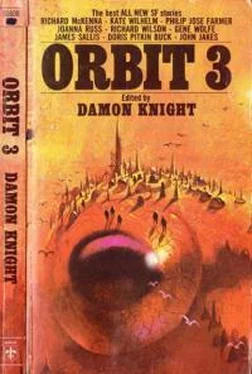

If Joanna Russ had consulted me before beginning to write her Alyx stories (see “I Gave Her Sack and Sherry” and “The Adventuress,” in Orbit 2), I would have told her nobody could get away with a series of heroic fantasies of prehistory in which the central character, the barbaric adventurer, is a woman. I would have been wrong, just as I was when I told Rosel George Brown she couldn’t sell a novel about a female private eye. [See Sibyl Sue Blue, Doubleday, 1966; Berkley, 1967 (published as Galactic Sibyl Sue Blue).]

It is a little idiotic, isn’t it, that women in adventure stories should have been restricted to the roles of simpering princesses and insatiable vampires? . . . and that even women writers, crushed by convention, should have been too timid to tell us what women are really like?

The attractive thing about Alyx is that she is not a cardboard fantasy figure, but a real person. And incidentally, this is the overlooked clue to the age-old “mystery” about women: they are people.

The Barbarian

by Joanna Russ

Alyx, the gray-eyed, the silent woman. Wit, arm, killquick for hire, she watched the strange man thread his way through the tables and the smoke toward her. This was in Ourdh, where all things are possible. He stopped at the table where she sat alone and with a certain indefinable gallantry, not pleasant but perhaps its exact opposite, he said:

“A woman—here?”

“You’re looking at one,” said Alyx dryly, for she did not like his tone. It occurred to her that she had seen him before—though he was not so fat then, no, not quite so fat—and then it occurred to her that the time of their last meeting had almost certainly been in the hills when she was four or five years old. That was thirty years ago. So she watched him very narrowly as he eased himself into the seat opposite, watched him as he drummed his fingers in a lively tune on the tabletop, and paid him close attention when he tapped one of the marine decorations that hung from the ceiling (a stuffed blowfish, all spikes and parchment, that moved lazily to and fro in a wandering current of air) and made it bob. He smiled, the flesh around his eyes straining into folds.

“I know you,” he said. “A raw country girl fresh from the hills who betrayed an entire religious delegation to the police some ten years ago. You settled down as a picklock. You made a good thing of it. You expanded your profession to include a few more difficult items and you did a few things that turned heads hereabouts. You were not unknown, even then. Then you vanished for a season and reappeared as a fairly rich woman. But that didn’t last, unfortunately.”

“Didn’t have to,” said Alyx.

“Didn’t last,” repeated the fat man imperturbably, with a lazy shake of the head. “No, no, it didn’t last. And now,” (he pronounced the “now” with peculiar relish) “you are getting old.”

“Old enough,” said Alyx, amused.

“Old,” said he, “old. Still neat, still tough, still small. But old. You’re thinking of settling down.”

“Not exactly.”

“Children?”

She shrugged, retiring a little into the shadow. The fat man did not appear to notice.

“It’s been done,” she said.

“You may die in childbirth,” said he, “at your age.”

“That, too, has been done.”

She stirred a little, and in a moment a short-handled Southern dagger, the kind carried unobtrusively in sleeves or shoes, appeared with its point buried in the tabletop, vibrating ever so gently.

“It is true,” said she, “that I am growing old. My hair is threaded with white. I am developing a chunky look around the waist that does not exactly please me, though I was never a ballet-girl.” She grinned at him in the semidarkness. “Another thing,” she said softly, “that I develop with age is a certain lack of patience. If you do not stop making personal remarks and taking up my time— which is valuable—I shall throw you across the room.”

Читать дальше