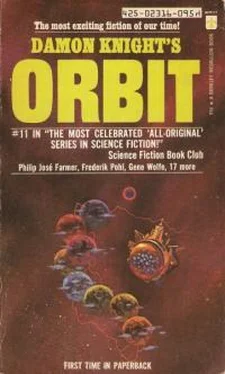

Дэймон Найт - Orbit 11

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Дэймон Найт - Orbit 11» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1973, ISBN: 1973, Издательство: Berkley Medallion, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 11

- Автор:

- Издательство:Berkley Medallion

- Жанр:

- Год:1973

- ISBN:0425023168

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 11: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 11»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 11 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 11», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In a sunny nursery on that glorious morning of 16 March 1944, Michael said “Mama,” his first word. It was raining in New Orleans, and unseasonably cold, and that word was one that Roger wouldn’t learn for some time. But at the same instant, he opened his mouth and said “No” to a spoonful of mashed carrots. The attendant didn’t know it was Roger’s first word, but was not disposed to coax, and Roger went hungry for the rest of the morning.

And the war ground on. Poor Michael had to be without his father for weeks at a time, when he journeyed to Washington or San Francisco or even New Orleans to confer with other powerful men. In these times, Mrs. Kidd redoubled her affection and tried to perk up the little tyke with gifts of toys and candy. He loved his father and missed him, but shrewdly learned to take advantage of his absences.

The orphanage in New Orleans lost men to the armed forces and the stronger women went out to rivet and weld and slap grey paint for the war. Roger’s family winnowed down to a handful of old ladies and bitter 4-F’s. Children would die every month from carelessness or simple lack of attention. They would soil their diapers and lie in the mess for most of the day. They would taste turpentine or rat poison and try to cope with the situation without benefit of adult supervision. Roger lived, though he didn’t thrive.

The boys were two years old when Japan capitulated. Michael sat at a garden party in New Rochelle and watched his parents and their friends drink champagne and kiss and laugh and wipe each other’s tears away. Roger was kept awake all night by the drunken brawl in the next room, and twice watched with childish curiosity as white-clad couples lurched into the ward and screwed clumsily beside his crib.

September after Michael’s fourth birthday, his mother tearfully left him in the company of ten other children and a professionally kind lady, to spend half of each day coping with the intricacies of graham crackers and milk, crayons and fingerpaints. His father had a cork board installed in his den, where he thumbtacked Michael’s latest creations. Mr. Kidd’s friends often commented on how advanced the youngster was.

The orphanage celebrated Roger’s fourth birthday the way they celebrated everybody’s. They put him to work. Every morning after breakfast he went to the kitchen, where the cook would give him a paper bag full of potatoes and a potato peeler. He would take the potatoes out of the bag and peel them one by one, very carefully making the peelings drop into the bag. Then he would take the bag of peelings down to the incinerator, where the colored janitor would thank him for it very gravely. Then he would return to wash the potatoes after he had scrubbed his own hands. This would take most of the morning—he soon learned that haste led only to cut fingers, and if there was the slightest spot on one potato, the cook would make him go over all of them once again.

Nursery school prepared Michael quite well for grade school, and he excelled in every subject except arithmetic. Mr. Kidd hired a succession of tutors who managed through wheedling and cajoling and sheer repetition to teach Michael first addition, then subtraction, then multiplication, and finally long division and fractions. When he entered high school, Michael was actually better prepared in mathematics than most of his classmates. But he didn’t understand it, really—the tutors had given him a superficial facility with numbers that, it was hoped, might carry him through.

Roger attended the orphanage grade school, where he did poorly in almost every subject. Except mathematics. The one teacher who knew the term thought that perhaps Roger was an idiot savant (but he was wrong). In the second grade, he could add up a column of figures in seconds, without using a pencil. In the third grade, he could multiply large numbers by looking at them. In the fourth grade, he discovered prime numbers independently and could crank out long division orally, without seeing the numbers. In the fifth grade someone told him what square roots were, and he extended the concept to cube roots, and could calculate either without recourse to pencil and paper. By the time he got to junior high school, he had mastered high school algebra and geometry. And he was hungry for more.

Now this was 1955, and the boys were starting to take on the appearances that they would carry through adult life. Michael was the image of his father; tall, slim, with a slightly arrogant, imperial cast to his features. Roger looked like one of nature’s lesser efforts. He was short and swarthy, favoring his mother, with a potbelly from living on starch all his life, a permanently broken nose, and one ear larger than the other. He didn’t resemble his father at all.

Michael’s first experience with a girl came when he was twelve. His riding teacher, a lovely wench of eighteen, supplied Michael with a condom and instructed him in its use, in a pile of hay behind the stables, on a lovely May afternoon.

On that same afternoon, Roger was dispassionately fellating a mathematics teacher only slightly uglier than he was, this being the unspoken price for tutelage into the mysteries of integral calculus. The experience didn’t particularly upset Roger. Growing up in an orphanage, he had already experienced a greater variety of sexual adventure than Michael would in his entire life.

In high school, Michael was elected president of his class for two years running. A plain girl did his algebra homework for him and patiently explained the subject well enough for him to pass the tests. In spite of his mediocre performance in that subject, Michael graduated with honors and was accepted by Harvard.

Roger spent high school indulging his love for mathematics, just doing enough work in the other subjects to avoid the boredom of repeating them. He applied to several colleges, just to get the counselor off his back, but in spite of his perfect score on the College Boards (Mathematics), none of the schools had an opening. He apprenticed himself to an accountant and was quite happy to spend his days manipulating figures with half his mind, while the other half worked on a theory of Abelian groups that he was sure would one day blow modern algebra wide open.

Michael found Harvard challenging at first, but soon was anxious to get out into the “real world”—helping Mr. Kidd manage the family’s widespread, subtle investments. He graduated cum laude, but declined graduate work in favor of becoming a junior financial adviser to his father.

Roger worked away at his books and at his theory, which he eventually had published in the SIAM Journal by the simple expedient of adding a Ph.D. to his name. He was found out, but he didn’t care.

At Harvard, Michael had taken ROTC and graduated with a Reserve commission in the infantry, at his father’s behest. There was a war going on now, in Vietnam, and his father, perhaps suffering a little from guilt at being too young for the first World War and too old for the second, urged his son to help out with the third.

Roger had applied for OCS at the age of twenty, and had been turned down (he never learned it was for “extreme ugliness of face”). At twenty-two, he was drafted; and the Army, showing rare insight, took notice of his phenomenal ability with numbers and sent him to artillery school. There he learned to translate cryptic commands like “Drop 50” and “Add 50” into exercises in analytic geometry that eventually led to a shell being dropped exactly where the forward observer wanted it. He loved to juggle the numbers and shout orders to the gun crew, who were in turn appreciative of his ability, as it lessened the amount of work for them—Roger never had a near miss that had to be repeated. Who cares if he looks like the devil’s brother-in-law? He’s a good man to have on the horn.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 11»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 11» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 11» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.