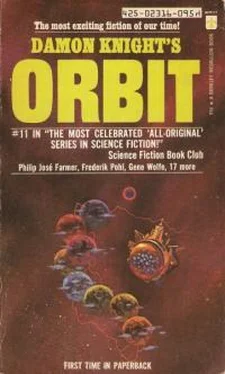

Дэймон Найт - Orbit 11

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Дэймон Найт - Orbit 11» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1973, ISBN: 1973, Издательство: Berkley Medallion, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 11

- Автор:

- Издательство:Berkley Medallion

- Жанр:

- Год:1973

- ISBN:0425023168

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 11: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 11»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 11 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 11», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Michael had learned to say “mama” again, but his mother wasn’t sure he could recognize her during her visits, which became less and less frequent as cancer spread through her body. On 9 June 1967, she died of the cervical cancer that had been discovered exactly one year before. Nobody told Michael.

On 9 June 1967, Roger had finished his first semester at the University of Chicago and was sitting in the parlor of the head of the mathematics department, drinking tea and discussing the paper that Roger had prepared, extending his new system of algebraic morphology. The department head had made Roger his protégé, and they spent many afternoons like this, the youth’s fresh insight cross-pollinating the professor’s great experience.

By May of 1970, Michael had learned to respond to his name by lifting his left forefinger.

Roger graduated summa cum laude on 30 May 1970 and, out of dozens of offers, took an assistantship at the California Institute of Technology.

Against his physician’s instructions, Mr. Kidd went on a skiing expedition to the Swiss alps. On an easy slope his ski hit an exposed root and, rolling comfortably with the fall, Michael’s father struck a half-concealed rock which fractured his spine. It was June 1973 and he would never ski again, would never walk again.

At that same instant on the other side of the world, Roger sat down after a brilliant defense of his doctoral thesis, a startling redefinition of Peano’s Axiom. The thesis was approved unanimously.

On Michael’s birthday, 12 April 1975, his father, acting through a bank of telephones beside his motorized bed, liquidated ninety percent of the family’s assets and set up a tax-sheltered trust to care for his only child. Then he took ten potent pain-killers with his breakfast orange juice and another twenty with sips of water and he found out that dying that way wasn’t as pleasant as he thought it would be.

It was also Roger’s thirty-second birthday, and he celebrated it quietly at home in the company of his new wife, a former student of his, twelve years his junior, who was dazzled by his genius. She could switch effortlessly from doting Hausfrau to randy mistress to conscientious secretary and Roger knew love for the first time in his life. He was also the youngest assistant professor on the mathematics faculty of CalTech.

On 4 January 1980, Michael stopped responding to his name. The inflation safeguards on his trust fund were eroding with time and he was moved out of the exclusive private clinic to a small room in San Francisco General.

The same day, due to his phenomenal record of publications and the personal charisma that fascinated students and faculty alike, Roger was promoted to be the youngest full professor in the history of the mathematics department. His unfashionably long hair and full beard covered his ludicrous ears and “extreme ugliness of face,” and people who knew the history of science were affectionately comparing him to Steinmetz.

There was nobody to give the tests, but if somebody had they would have found that on 12 April 1983, Michael’s iris would no longer respond to the difference between a circle and a square.

On his fortieth birthday, Roger had the satisfaction of hearing that his book, Modern Algebra Redefined, was sold out in its fifth printing and was considered required reading for almost every mathematics graduate student in the country.

Seventeen June 1985 and Michael stopped breathing; a red light blinked on the attendant’s board and he administered mouth-to-mouth resuscitation until they rolled in an electronic respirator and installed him. Since he wasn’t on the floor reserved for respiratory disease, the respirator was plugged into a regular socket instead of the special failsafe line.

Roger was on top of the world. He had been offered the chairmanship of the mathematics department of Penn State, and said he would accept as soon as he finished teaching his summer postdoctoral seminar on algebraic morphology.

The hottest day of the year was 19 August 1985. At 2:45:20 p.m. the air conditioners were just drawing too much power and somewhere in Central Valley a bank of bus bars glowed cherry red and exploded in a shower of molten copper.

All the lights on the floor and on the attendant’s board went out, the electronic respirator stopped, and while the attendant was frantically buzzing for assistance, 2:45:25 to be exact, Michael Tobias Kidd passed away.

The lights in the seminar room dimmed and blinked out. Roger got up to open the Venetian blinds, whipped off his glasses in a characteristic gesture and was framing an acerbic comment when, at 2:45:25, he felt a slight tingling in his head as a blood vessel ruptured and quite painlessly he went to join his brother.

Steve Herbst

OLD SOUL

Alice Costin went in to check on the patient at two in the morning. At that time the hall was quiet. Mr. Wile awoke when she came in. His eyes followed her around the room. Alice looked down at him.

“Mr. Wile, you should be sleeping. Is everything all right?”

Painfully, eyes wet and sad, Mr. Wile nodded. He watched her empty his bedpan and rinse it out. Watched her straighten the sheet over him. Alice went out, closed the door, left him in darkness.

“Good night.”

She was a young black woman; her brown eyes shone. She could not think about his whiteness, his dying paleness. Mr. Wile’s private doctor was still prescribing treatments. Useless. Mr. Wile was doing very poorly.

There was a man in the hall with a machine, polishing the floor. The circular smears shone. The man said, “Long night, ain’t it?” Alice waved at him and walked until she came to a stairwell. Downstairs by her locker, she took the rubber band out of her hair, took off her white uniform and stockings and put on a skirt and sweater. Didn’t want to wear the uniform home.

Noise came from other lockers, the owners of which she could not see. Without saying hello to anybody, Alice went upstairs and all the way down a corridor to a side door.

She was glad to be outside. Thanked God to be able to leave.

The bus came right away. Inside, it was brightly lit. Riding it home, Alice saw what she had seen times without number before. At two thirty all the apartments were dark, and all the phone-booth lights were broken. Very few people were on the street; the ends of their cigarettes were the only things anywhere that were not blue. Warm breeze came through the bus window.

Alice was not at all sleepy. If her husband was home now, she could crawl sweaty into bed with him and hear his rough breathing. In the morning after he had left for his job, she would go back to sleep. At noon she would see Trudy and Michael back from school. That was plenty of time to sleep, and be up all afternoon. Spend the afternoon, hot and busy, with her sister. Go back to work. . . .

The bus let her off and she walked, watched, two blocks to her apartment. The kitchen light was on; she came up the back way and unlocked the door. Everybody was asleep. She turned off the light. In bed, quiet enveloped her. Only the faint sound of a car on the street below broke the silence. Her husband was not there. Alice drew the cool sheet around her.

By the stream there are ducks, but to run toward them would be to make them swim away. In the moonlight and waiting for bedtime, everything is awkward. There is nothing comfortable to say. The girl bends over the stream to wet her hands. Standing up she brushes hair out of her eyes. Fingers run down the sides of her face. Behind her is the bridge, and against the dark-blue sky is the farmhouse, painted red with white borders. It is almost time to go back.

The next night Alice was asked to look after an emergency case. She was sorry that she could do so little for him. The young man had been in a knife fight. He had been pounding the streets angry, and another man had challenged him. The emergency case had stuck his own knife in himself, in a spiteful rage. Now he was waiting wordless on a metal bench to be healed. A doctor bandaged him up and he was moved to a bed. Alice changed the washrag on his forehead, while he writhed from the pain in his chest muscles.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 11»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 11» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 11» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.