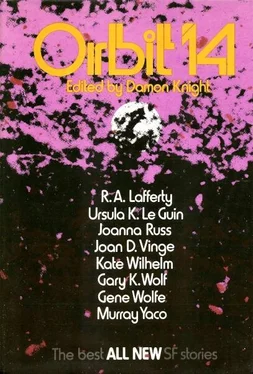

Damon Knight - Orbit 14

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Damon Knight - Orbit 14» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1974, ISBN: 1974, Издательство: Harper & Row, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 14

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper & Row

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- ISBN:0-06-012438-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 14: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 14»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 14 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 14», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Water.”

“No lack of that. Come on, I’ll show you. Beneath here in the lower level there’s all too many springs. You turned the wrong direction. I used to work down there, with the damned cold water up to my knees, before the vein ran out. A long time ago. Come on.”

The old miner left him in his camp, after showing him where the spring rose and warning him not to follow down the watercourse, for the timbering would be rotted and a step or sound might bring the earth down. Down there all the timbers were covered with a deep glittering white fur: saltpeter perhaps, or a fungus; it was very strange, above the oily water. When he was alone again Guennar thought he had dreamed that white tunnel full of black water, and the visit of the miner. When he saw a flicker of light far down the tunnel, he crouched behind the quartz buttress with a great wedge of granite in his hand: for all his fear and anger and grief had come down to one thing here in the darkness, a determination that no man would lay hand on him. A blind determination, blunt and heavy as a broken stone, heavy in his soul.

It was only the old man coming, with a hunk of dry cheese for him.

He sat with the astronomer, and talked. Guennar ate up the cheese, for he had no food left, and listened to the old man talk. As he listened the weight seemed to lift a little, he seemed to see a little farther in the dark.

“You’re no common soldier,” the miner said, and he replied, “No, I was a student once,” but no more, because he dared not tell the miner who he was. The old man knew all the events of the region; he spoke of the burning of the “Round House” on the hill, and of Count Bord. “He went off to the city with them, with these black-gowns, to be tried, they do say, to come before their council. Tried for what? what did he ever do but hunt boar and deer and foxen? is it the council of the foxen trying him? What’s it all about, this snooping and soldiering and burning and trying? Better leave honest folk alone. The count was honest, as far as the rich can be, a fair landlord. But you can’t trust them, none of such folk. Only down here. You can trust the men who go down into the mine. What else has a man got down here but his own hands and his mates’ hands? What’s between him and death, when there’s a fall in the level or a winze closes and he’s in the blind end, but their hands, and their shovels, and their will to dig him out? There’d be no silver up there in the sun if there wasn’t trust between us down here in the dark. Down here you can count on your mates. And nobody comes but them. Can you see the owner in his lace, or the soldiers, coming down the ladders, coming down and down the great shaft into the dark? Not them! They’re brave at tramping on the grass, but what good’s a sword and shouting in the dark? I’d like to see ’em come down here . . .”

The next time he came another man was with him, and they brought an oil lamp and a clay jar of oil, as well as more cheese, bread, and some apples. “It was Hanno thought of the lamp,” the old man said. “A hempen wick it is, if she goes out blow sharp and she’ll likely catch up again. Here’s a dozen candles, too. Young Per swiped the lot from the doler, up on the grass.”

“They all know I’m here?”

“We do,” the miner said briefly. “They don’t.”

Some time after this, Guennar returned along the lower, westleading level he had followed before, till he saw the miners’ candles dance like stars; and he came into the stope where they were working. They shared their meal with him. They showed him the ways of the mine, and the pumps, and the great shaft where the ladders were and the hanging pulleys with their buckets; he sheered off from that, for the wind that came sucking down the great shaft smelled to him of burning. They took him back and let him work with them. They treated him as a guest, as a child. They had adopted him. He was their secret.

There is not much good spending twelve hours a day in a black hole in the ground all your life long if there’s nothing there, no secret, no treasure, nothing hidden.

There was the silver, to be sure. But where ten crews of fifteen had used to work these levels and there had been no end to the groan and clatter and crash of the loaded buckets going up on the screaming winch and the empties banging down to meet the trammers running with their heavy carts, now one crew of eight men worked: men over forty, old men, who had no skill but mining. There was still some silver there in the hard granite, in little veins among the gangue. Sometimes they would lengthen an end by one foot in two weeks.

“It was a great mine,” they said with pride.

They showed the astronomer how to set a gad and swing the sledge, how to go at granite with the finely balanced and sharp-pointed pick, how to sort and “cob,” what to look for, the rare bright branchings of the pure metal, the crumbling rich rock of the ore. He helped them daily. He was in the stope waiting for them when they came, and spelled one or another on and off all day with the shovel work, or sharpening tools, or running the ore cart down its grooved plank to the great shaft, or working in the ends. There they would not let him work long; pride and habit forbade it. “Here, leave off chopping at that like a woodcutter. Look, this way: see?” But then another would ask him, “Give me a blow here, lad, see, on the gad, that’s it.”

They fed him from their own coarse meager meals.

In the night, alone in the hollow earth, when they had climbed the long ladders up “to grass” as they said, he lay and thought of them, their faces, their voices, their heavy, scarred, earth-stained hands, old men’s hands with thick nails blackened by bruising rock and steel; those hands, intelligent and vulnerable, which had opened up the earth and found the shining silver in the solid rock. The silver they never held, never kept, never spent. The silver that was not theirs.

“If you found a new vein, a new lode, what would you do?”

“Open her, and tell the masters.”

“Why tell the masters?”

“Why, man! we gets paid for what we brings up! D’you think we does this damned work for love?”

“Yes.”

They all laughed at him, loud, jeering laughter, innocent. The living eyes shone in their faces blackened with dust and sweat.

“Ah, if we could find a new lode! The wife would keep a pig like we had once, and by God I’d swim in beer! But if there’s silver they’d have found it; that’s why they pushed the workings so far east. But it’s barren there, and worked out here, that’s the short and long of it.”

Time stretched behind him and ahead of him like the dark drifts and crosscuts of the mine, all present at once, wherever he with his small candle might be among them. When he was alone now the astronomer often wandered in the tunnels and the old stopes, knowing the dangerous places, the deep levels full of water, adept at shaky ladders and tight places, intrigued by the play of his candle on the rock walls and faces, the glitter of mica that seemed to come from deep inside the stone. Why did it sometimes shine out that way? as if the candle found something far within the shining broken surface, something that winked in answer and occulted, as if it had slipped behind a cloud or an unseen planet’s disk.

“There are stars in the earth,” he thought. “If one knew how to see them.”

Awkward with the pick, he was clever with machinery; they admired his skill, and brought him tools. He repaired pumps and windlasses; he fixed up a lamp on a chain for “young Per” working in a long narrow dead-end, with a reflector made from a tin candle holder beaten out into a curved sheet and polished with fine rockdust and the sheepskin lining of his coat. “It’s a marvel,” Per said. “Like daylight. Only, being behind me, it don’t go out when the air gets bad, and tell me I should be backing out for a breath.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 14»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 14» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 14» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.