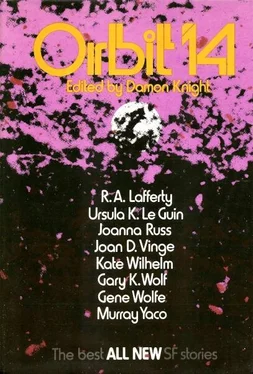

Damon Knight - Orbit 14

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Damon Knight - Orbit 14» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1974, ISBN: 1974, Издательство: Harper & Row, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 14

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper & Row

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- ISBN:0-06-012438-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 14: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 14»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 14 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 14», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“I don’t see nothing but the ground,” the old man said after a long and solemn observation with the instrument. “And the little dust and pebbles on it.”

“The lamp blinds your eyes, perhaps,” the astronomer said with humility. “It is better to look without light. I can do it because I have done it for so long. It is all practice—like placing the gads, which you always do right, and I always do wrong.”

“Aye. Maybe. Tell me what you see—” Bran hesitated. He had not long ago realized who Guennar must be. Knowing him to be a heretic made no difference, but knowing him to be a learned man made it hard to call him “mate” or “lad.” And yet here, and after all this time, he could not call him “Master.” There were times when for all his mildness the fugitive spoke with great words, gripping one’s soul, times when it would have been easy to call him Master. But it would have frightened him.

The astronomer put his hand on the frame of his mechanism and replied in a soft voice, “There are . . . constellations.”

“What’s that, constellations?”

The astronomer looked at Bran as if from a great way off, and said presently, “The Wain, the Scorpion, the Sickle by the Milky Way in summer, those are constellations. Patterns of stars, gatherings of stars, parenthoods, semblances . . .”

“And you see those here, with this?”

Still looking at him through the weak lamplight with clear brooding eyes, the astronomer nodded, and did not speak, but pointed downward, at the rock on which they stood, the.hewn floor of the mine.

“What are they like?” Bran’s voice was hushed.

“I have only glimpsed them. Only for a moment. I have not learned the skill; it is a somewhat different skill . . . But they are there, Bran.”

Often now he was not in the stope when they came to work, and did not join them even for their meal, though they always left him a share of food. He knew the ways of the mine now better than any of them, even Bran, not only the “living” mine but the “dead” one, the abandoned workings and exploratory tunnels that ran eastward, ever deeper, toward the caves. There he was most often; and they did not follow him.

When he did appear amongst them and they talked with him, they were more timid with him, and did not laugh.

One night as they were all going back with the last cartload to the main shaft, he came to meet them, stepping suddenly out of a crosscut to their right. As always, he wore his ragged sheepskin coat, black with the clay and dirt of the tunnels. His fair hair had gone grey. His eyes were clear. “Bran,” he said, “come, I can show you now.”

“Show me what?”

“The stars. The stars beneath the rock. There’s a great constellation in the stope on the old fourth level, where the white granite cuts down through the black.”

“I know the place.”

“It’s there: underfoot, by that wall of white rock. A great shining and assembly of stars. Their radiance beats up through the darkness. They are like the faces of dancers, the eyes of angels. Come and see them, Bran!”

The miners stood there, Per and Hanno with backs braced to hold the cart from rolling: stooped men with tired, dirty faces and big hands bent and hardened by the grip of shovel and pick and sledge. They were embarrassed, compassionate, impatient.

“We’re just quitting. Off home to supper. Tomorrow,” Bran said. The astronomer looked from one face to another and said nothing.

Hanno said in his hoarse gentle voice, “Come up with us, for this once, lad. It’s dark night out, and likely raining; it’s November now; no soul will see you if you come and sit at my hearth, for once, and eat hot food, and sleep beneath a roof and not under the heavy earth all by yourself alone!”

Guennar stepped back. It was as if a light went out, as his face went into shadow. “No,” he said. “They will burn out my eyes.”

“Leave him be,” said Per, and set the heavy ore-cart moving toward the shaft.

“Look where I told you,” Guennar said to Bran. “The mine is not dead. Look with your own eyes.”

“Aye. I’ll come with you and see. Good night!”

“Good night,” said the astronomer, and turned back to the side tunnel as they went on. He carried no lamp or candle; they saw him one moment, darkness the next.

In the morning he was not there to meet them. He did not come.

Bran and Hanno sought him, idly at first, then for one whole day. They went as far down as they dared, and came at last to the entrance of the caves, and entered, calling sometimes, though in the great caverns even they, miners all their lives, dared not call aloud because of the terror of the endless echoes in the dark.

“He has gone down,” Bran said. “Down farther. That’s what he said. Go farther, you must go farther, to find the light.”

“There is no light,” Hanno whispered. “There was never light here. Not since the world’s creation.”

But Bran was an obstinate old man, with a literal and credulous mind; and Per listened to him. One day the two went to the place the astronomer had spoken of, where a great vein of hard light granite that cut down through the darker rock had been left untouched, fifty years ago, as barren stone. They retimbered the roof of the old stope where the supports had weakened, and began to dig, not into the white rock but down, beside it; the astronomer had left a mark there, a kind of chart or symbol drawn with candleblack on the stone floor. They came on silver ore a foot down, beneath the shell of quartz; and under that—all eight of them working now—the striking picks laid bare the raw silver, the veins and branches and knots and nodes shining among broken crystals in the shattered rock, like stars and gatherings of stars, depth below depth without end, the light.

A BROTHER TO DRAGONS, A COMPANION OF OWLS

Kate Wilhelm

This is the rejoicing city that dwelt carelessly, that said in her heart, I am, and there is none beside me: how is she become a desolation, a place for beasts to lie down in! every one that passeth by her shall hiss, and wag his hand.

It is late in the afternoon, a warm, hazy autumn day; the frost has already turned the leaves golden and scarlet, and the insects are quieted for the season. Although there are no fires in the city, no smokestacks sending clouds to meet clouds, the air is somehow thick and blurs the outlines of things in the distance. In the distance the buildings seem more blue than stone-colored, more grey than they are, and they have no distinct edges. Finally the canyons of the buildings and the thick air blend and there is only the grey-blue. The city is still.

In the fourth-floor apartment of one of the buildings overlooking a park, an old man sits at a table that is six feet long, covered with books and notebooks. There is a kerosene lamp on the table, not lighted at this hour. The books are Bibles, and a concordance that is a thousand pages thick. Another table abuts the work table, and it is covered also, but most of the material there is the old man’s writing. Notebooks filled, others opened, not yet completed, card files, piles of notes on yellow paper.

The old man is bent over the table, following a line of print with his finger, pursing his lips, his face rigid with concentration. He wears glasses that are not properly fitted, and now and again he pushes them onto the bridge of his nose. Occasionally he pauses in his reading and looks at the park across the street, the source of the yellow in the light. The trees at this end of the park are almost uniformly gold now. The old man thinks that one day he will study the trees and relearn their names—he knew them once—and the names of the flowers that are still blooming, having become naturalized in the park long ago. Wildflowers, that is all he knows about them. They are yellow also. The old man thinks that it is shameful that he knows so little about the trees, the flowers, the insects. They all have names, every tree its own name, every kind of grass, every kind of insect. The clouds. The kinds of soils, the rocks. And he knows none of them. Only recently has he begun to have such thoughts. He rubs his eyes; they tend to water after reading too long, and he wonders why so many of the Bibles were printed in such small type. He thinks it was to save paper, to keep the weight manageable, but that is only a guess. Perhaps it was custom. He pushes his glasses up firmly and bends over the books again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 14»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 14» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 14» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.