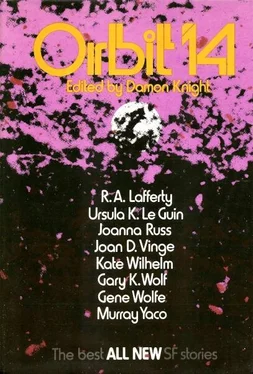

Damon Knight - Orbit 14

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Damon Knight - Orbit 14» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1974, ISBN: 1974, Издательство: Harper & Row, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 14

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper & Row

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- ISBN:0-06-012438-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 14: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 14»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 14 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 14», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“There are children in the city, Monica! You should not show any lights tonight, until we decide what to do. Do you understand?”

Monica is pouting. She looks away from him and he is afraid she is going to weep because he has spoiled her surprise. The old man begins to turn off the lanterns. Monica doesn’t look at him. She is a silhouette against the pale sky, slender still, elegant-looking with her hair carefully done up, wearing a long dress that, in this dim light, no longer shows the slits where brittle age has touched it. She is looking at the city when he leaves.

Now the stars are out, and the streets are too dark to see more than a hundred yards in any direction. The old man hesitates outside the church, then resolutely goes inside and climbs to the belfry. The bell has always been their signal to gather. And if the children hear? He shakes his head and pulls the rope; the bell sounds alarmingly loud. The children already know there is someone in the city, and perhaps they are still too far from this area to hear the bell. He catches the clapper before it can strike a second time.

He waits in the church for the others to assemble, and he tries to remember when the last night session was called. He has only one candle burning, its light far from the massive doors. As the others arrive, the one light is a message, and they become subdued and fearful as they enter and silently go to the front of the church. They are as quiet as ghosts, they look like ghosts in their floor-length robes and capes. Sixteen of the surviving twenty-two residents attend the meeting. The old man waits until it seems likely that no one else will come, and then he tells them about the children. For an hour they talk. There is Sam Whitten, the senior member, who is senile and can’t cope with the idea of children at all. There is Sandra Littleton, who wants an expedition sent out immediately to find the children, bring them in to the warmth of her fires, who wants to feed them, school them, care for them. There is Jake Pulaski, who thinks they should be caught and killed. Someone else wants them run out of town again. Another thinks everyone should hide and let the children roam until they get tired and leave. And so on, for an hour. Nothing is decided.

Boy is still hiding when the old man returns to his apartment. He may hide for days or weeks. The old man prepares his dinner and eats it in an inner room where the lights won’t show, and then he stands at the window looking at the dark city for a long time. The old man and Boy are the only ones who live in rooms this high; everyone else has found a first- or second-floor apartment, or a house, and sometimes they complain about the old man’s stairs. Sometimes they have to stand in the street and shout for him when they need his help. Recently the old man’s legs have been bothering him a bit, not much, not often, but it is an indication that before long he will have to descend a floor or two. He will do it reluctantly. He likes to be able to look out over the city, to be above the trees.

It is very cold when he finally goes to bed, chilled. He has decided not to have a fire. No fire, no smoke, no lights. Not yet. Sometime in the night Monica slips into his bed.

“Lew, are there really children?”

“Boy says so.”

She is silent, warmer than he is, sharing her warmth with him.

“And we have grown so used to thinking that we were the last,” she says after a long time. “Everything will change now, won’t it?”

“I don’t know. Maybe they’ll just vanish again.”

Neither of them believes this. After a time they sleep, and when the old man awakens, at the first vague light of dawn, Monica is gone. He lies in the warm bed and thinks about the many nights they shared, not for warmth, and he has no regrets, only a mild curiosity that it could have died as it did, leaving memories without bitterness.

The children play in the rubble of the burned-out block of apartments visible from the old man’s building, between the park and the river warehouse district. The old man is standing at an eighthfloor window watching one of them, a small girl, through a telescope that brings her so close he feels he can reach out and touch her golden hair. There are seven of them, the oldest probably no more than thirteen, the youngest, the blond girl, about five or six.

“Let me have a turn, Lew,” Myra Olney says. Her eyes are red. She has been weeping ever since she first saw the children. She is waiting for her son Timmy to come home. Timmy has been dead for fifty-five years. The old man moves aside, and Myra swings the telescope too far and loses the children. Walter Gilson adjusts it for her and rejoins the others.

“We can’t just ignore them, pretend they don’t exist,” Walter says. He hoists his robe to sit down, and it drapes between his knees. Only three of the men still wear trousers. Their robes are made of wool, old blankets, cut-apart overcoats sewn together in a more practical style. The wool holds up better than any other material. The synthetics have split and cracked as they aged.

“Just exactly what did Boy say?” Sid Elliston asks for the third time.

“I told you. He said they tried to catch him. He could have been frightened and imagined it. You know he’s terrified of anything out of the ordinary.”

They all know about Boy. He is cleverer than most of them about practical things: he found the tanks they all use to collect water on the roofs, and the pipes to provide running water. He found nuts and a grinder, so they have flour of a sort. He found the hospital supplies deep in a hidden vault. They know that without Boy their lives would be much harder, perhaps impossible. Also, they know that Boy is strange.

Sid has taken Myra’s place at the telescope, and she sits by the old man and clutches his arm and pleads with him. They all seem to regard the children as his problem, perhaps because Boy found them, and they know Boy is his problem.

“You have to go out there and bring them in,” Myra says, weeping. “It’s getting colder and colder. They’ll freeze.”

“They’ve managed to stay alive this long,” Harry Gould says. “Let them go back to where they came from. It could be a trap. They draw us out and then others grab our houses, our food.”

“You know we could feed a hundred times that many,” Walter says. “They ain’t carrying nothing. What do you suppose they’ve been eating?”

“Small game,” someone suggests. “Boy says there are rabbits right here in the city, and birds. I saw some birds last week. Robins.”

The old man shakes his head. Not robins. They come in the spring, not in the fall.

He goes back to the window, and Sid doesn’t question his right to the telescope but moves aside at his approach. The old man locates the children and searches for the little blond girl. They are throwing sticks and stones at something, he can’t make out what it is. A can? There are no cans; they have all rusted away. A rat? He wonders if there are rats again. Monica has told him that before he arrived in the city there were millions of rats, but their numbers have dwindled, and he has seen none at all for five years or more.

“We will bring them in,” he says suddenly, and leaves the window. “We can’t let them starve or freeze.”

“It’s our God-given duty,” Myra says tearfully, “to care for them. It’s the start of everything again. I knew it couldn’t all just end like that. I knew it!”

“We’ll have to educate them! Teach them math and literature!”

“Maybe they’ll be able to make the lights work again!”

“And they will plant crops. Com. Wheat. String beans.”

“And keep cattle. I can teach them how to milk. My father had fifty head of cattle on his farm. I know how to milk.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 14»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 14» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 14» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.