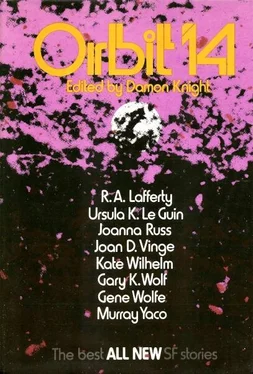

Damon Knight - Orbit 14

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Damon Knight - Orbit 14» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1974, ISBN: 1974, Издательство: Harper & Row, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 14

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper & Row

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- ISBN:0-06-012438-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 14: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 14»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 14 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 14», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The astronomer held the pommel with one hand. The other hand, which had been burned across the palm and fingers when he picked up a metal fragment still red-hot under its coat of cinders, he kept pressed against his thigh. He was not conscious of doing so, nor of the pain. Sometimes his senses told him, “I am on horseback,” or, “It’s getting lighter,” but these fragmentary messages made no sense to him. He shivered with cold as the dawn wind rose, rattling the dark woods by which the two men and the horse now passed in a deep lane overhung by teasel and brier; but the woods, the wind, the whitening sky, the cold were all remote from his mind, in which there was nothing but a darkness shot with the reek and heat of burning.

Bord made him dismount. There was sunlight around them now, lying long on rocks above a river valley. There was a dark place, and Bord urged him and pulled him into the dark place. It was not hot and close there but cold and silent. As soon as Bord let him stop he sank down, for his knees would not bear; and he felt the cold rock against his seared and throbbing hands.

“Gone to earth, by God!” said Bord, looking about at the veined walls, marked with the scars of miners’ picks, in the light of his lanterned candle. “I’ll be back; after dark, maybe. Don’t come out. Don’t go farther in. This is an old adit, they haven’t worked this end of the mine for years. May be slips and pitfalls in these old tunnels. Don’t come out! Lie low. When the hounds are gone, we’ll run you across the border.”

Bord turned and went back up the adit in darkness. When the sound of his steps had long since died away, the astronomer lifted his head and looked around him at the dark walls and the little burning candle. Presently he blew it out. There came upon him the earth-smelling darkness, silent and complete. He saw green shapes, ochreous blots drifting on the black; these faded slowly. The dull, chill black was balm to his inflamed and aching eyes, and to his mind.

If he thought, sitting there in the dark, they were not thoughts that found words. He was feverish from exhaustion and smoke inhalation and a few slight burns, and in an abnormal condition of mind; but perhaps his mind’s workings, though lucid and serene, had never been normal. It is not normal for a man to spend twenty years grinding lenses, building telescopes, peering at stars, making calculations, lists, maps and charts of things which no one knows or cares about, things which cannot be reached, or touched, or held. And now all that which he had spent his life on was gone, burned. What was left of him might as well be, as it was, buried.

But it did not occur to him, this idea of being buried. All he was keenly aware of was a great burden of anger and grief, a burden he was unfit to carry. It was crushing his mind, crushing out reason. And the darkness here seemed to relieve that pressure. He was accustomed to the dark, he had lived at night. The weight here was only rock, only earth. No granite is so hard as hatred and no clay so cold as cruelty. The earth’s black innocence enfolded him. He lay down within it, trembling a little with pain and with relief from pain, and slept.

Light waked him. Count Bord was there, lighting the candle with flint and steel. Bord’s face was vivid in the light: the high color and blue eyes of a keen huntsman, a red mouth, sensual and obstinate. “They’re on the scent,” he was saying. “They know you got away.”

“Why . . .” said the astronomer. His voice was weak; his throat, like his eyes, was still smoke-inflamed. “Why are they after me?”

“Why? Do you still need telling? To burn you alive, man! For heresy!” Bord’s blue eyes glared through the steadying glow of the candle.

“But it’s gone, burned, all I did.”

“Aye, the earth’s stopped, all right, but where’s their fox? They want their fox! But damned if I’ll let them get you.”

The astronomer’s eyes, light and wide-set, met his and held.

“Why?”

“You think I’m a fool,” Bord said with a grin that was not a smile, a wolf’s grin, the grin of the hunted and the hunter. “And I am one. I was a fool to warn you. You never listened. I was a fool to listen to you. But I liked to listen to you. I liked to hear you talk about the stars and the courses of the planets and the ends of time. Who else ever talked to me of anything but seed corn and cow dung? Do you see? And I don’t like soldiers and strangers, and trials and burnings. Your truth, their truth. What do I know about the truth? Am I a master? Do I know the courses of the stars? Maybe you do. Maybe they do. All I know is you have sat at my table and talked to me. Am I to watch you burn? God’s fire, they say; but you said the stars are the fires of God. Why do you ask me that, ‘Why?’ Why do you ask a fool’s question of a fool?”

“I am sorry,” the astronomer said.

“What do you know about men?” the count said. “You thought they’d let you be. And you thought I’d let you burn.” He looked at Guennar through the candlelight, grinning like a driven wolf, but in his blue eyes there was a glint of real amusement. “We who live down on the earth, you see, not up among the stars . . .”

He had brought a tinder box and three tallow candles, a bottle of water, a ball of pease pudding, a sack of bread. He left soon, warning the astronomer again not to venture out of the mine.

When Guennar woke again a strangeness in his situation troubled him, not one which would have worried most people hiding in a hole to save their skin, but most distressing to him: he did not know the time.

It was not clocks he missed, the sweet banging of the church bells in the villages calling to morning and evening prayer, the delicate and willing accuracy of the timepieces he used in his observatory and on whose refinement so many of his discoveries had depended; it was not the clocks he missed, but the great clock.

Not seeing the sky, one cannot know the turning of the earth. All the processes of time, the sun’s bright arch and the moon’s phases, the planets’ dance, the wheeling of the constellations around the pole star, the vaster wheeling of the seasons of the stars, all these were lost, the warp on which his life was woven.

Here there was no time.

“O my God,” Guennar the astronomer prayed in the darkness under ground, “how can it offend you to be praised? All I ever saw in my telescopes was one spark of your glory, one least fragment of the order of your creation. You could not be jealous of that, my Lord! And there were few enough who believed me, even so. Was it my arrogance in daring to describe your works? But how could I help it, Lord, when you let me see the endless fields of stars? Could I see and be silent? O my God, do not punish me any more, let me rebuild the smaller telescope. I will not speak, I will not publish, if it troubles your holy Church. I will not say anything more about the orbits of the planets or the nature of the stars. I will not speak, Lord, only let me see!”

“What the devil, be quiet, Master Guennar. I could hear you halfway up the tunnel,” said Bord, and the astronomer opened his eyes to the dazzle of Bord’s lantern. “They’ve called the full hunt up for you. Now you’re a necromancer. They swear they saw you sleeping in your house when they came, and they barred the doors; but there’s no bones in the ashes.”

“I was asleep,” Guennar said, covering his eyes. “They came, the soldiers ... I should have listened to you. I went into the passage under the dome. I left a passage there so I could go back to the hearth on cold nights. When it’s cold my fingers get too stiff, I have to go warm my hands sometimes.” He spread out his blistered, blackened hands and looked at them vaguely. “Then I heard them .overhead . . .”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 14»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 14» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 14» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.