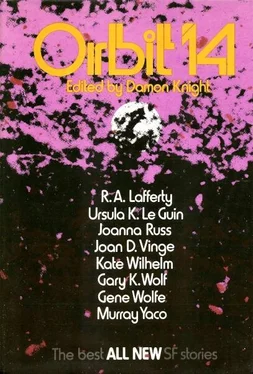

Damon Knight - Orbit 14

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Damon Knight - Orbit 14» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1974, ISBN: 1974, Издательство: Harper & Row, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Orbit 14

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper & Row

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- ISBN:0-06-012438-5

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Orbit 14: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Orbit 14»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Orbit 14 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Orbit 14», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Aldiss is at his best in discussing the literary progenitors of science fiction; he is illuminating on Walpole and Beckford, brilliant on Poe. Surprisingly, he devotes more than half his book to authors who he says did not write s.f. Although he quotes Kingsley Amis’s famous couplet, 11 11 “Si’s no good,” they bellow till we’re deaf. “But this looks good.”.—“Well then, it’s not sf.”

he appears to say, in several convoluted sentences, 12 12 E.g., “The greatest of these books would be the greatest of science fiction books if they were science fiction; but they are not, and it is only the growth of the genre since, stimulated by their vigorous example, which makes them seem to resemble it as much as they do.”

that Jonathan Swift, Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce & Co. did not write s.f. because they wrote literature. But if their literature is not s.f., why not? Aldiss does not say. By ducking the problem in this traditional and circular way he vitiates his argument and leaves the question as vexed as ever.

In dealing with Wells, Heinlein, and Edgar Rice Burroughs, Aldiss is penetrating and witty. He is illuminating on the subject of such writers as Lewis Padgett (but he gives all the credit to Kutt-ner, forgetting that C. L. Moore was part of that by-line too), Olaf Stapledon, and Walter Miller, Jr. (“cordon bleu pemmican”). He does somewhat less well with Haggard, “Saki,” Chesterton, Hodgson, Kafka, and Lovecraft, and astonishingly misjudges van Vogt (good God, “tenderness”!).

About Gernsbackian s.f. he writes, “As long as the stories were built like diagrams, and made clear like diagrams, and stripped of atmosphere and sensibility, then it did not seem to matter how silly the ‘science’ or the psychology was.” And about the New Wave: “To argue for either side in such a controversy is a mistake; phonies are thick on either hand, good writers few.” There is much sound sense here, along with a certain amount of inevitable tedium. In the end, the book is faintly disappointing because of its muddy conception; Aldiss never confronts the problem of deciding what his subject is, and as a result he takes in at once too much and too little.

The book is marred by many evidences of haste, and by a coy use of French (“the more au fait citizens”) and a genteel avoidance of the word “I” (“for this critic’s taste”). Aldiss sometimes attempts American slang, e.g., “the wish to escape from urban civilization, where there are lousy jobs like railroad cop going.”

Like Aldiss, Lin Carter lays his groundwork in a chapter of namedropping—Gilgamesh, the Vedic hymns, the Odyssey, Akhnaton’s Hymn to the Sun, etc. It is evident that he loves his subject enough actually to have read these works and many others. He writes knowledgeably of the Mabinogion and of Beckford’s Vathek. His discussions of William Morris and Lord Dunsany, and of Tolkien (for whom he has a measured enthusiasm), are lucid and informative. His style is chatty, well larded with cliches. Like Aldiss, he has a healthy sense of his own unique importance; like Aldiss, he graces his text with many gratuitous allusions to himself and his works. Although his book is subtitled “The Art of Fantasy,” and Carter maintains it is the first ever written on that subject, after the first few chapters it quickly narrows down to the kind of thing Carter writes himself, i.e., sword & sorcery. Within this narrow focus Carter’s judgment is reliable if lenient; outside it, he is undependable. (He dismisses Thurber’s The Thirteen Clocks as “essentially a sort of joke” because it scans and occasionally rhymes.) His chapter on technical problems is stupefyingly dull; he solemnly informs us that a kingdom is not the same thing as an empire, that great cities frequently arise near the mouths of rivers, etc. He quotes with approval C. S. Lewis’s list of examples of realistic details in fiction, then, by his additions to it, shows that he has completely missed the point. He introduces the idea of stage business in fiction and manages to misunderstand that. The latter half of his book is trivial because its subject is trivial.

Nevertheless, these books give eloquent testimony of the two kinds of fascination that keep s.f. and fantasy obstinately alive. Aldiss: “These days, we all have two heads. Frankenstein’s monster plunges along beside us, keeping just below the Plimsoll line of consciousness, buoyant with a life of its own.” Carter: “All I know is that something within me wakes and thrills and responds to phrases like ‘the splendid city of Celephais, in the Valley of Ooth-Nargai, beyond the Tanarian Hills,’ where galleys ‘sail up the river Oukranos past the gilded spires of Thran,’ and ‘elephant caravans tramp through perfumed jungles in Kled,’ where ‘forgotten palaces with veined ivory columns sleep lovely and unbroken under the moon.’ ”

Damon Knight

THE STARS BELOW

Ursula K. Le Guin

Only a madman would look for them underground.

The wooden house and outbuildings caught fire fast, blazed up, burned down, but the dome, built of lath and plaster above a drum of brick, would not burn. What they did at last was heap up the wreckage of the telescopes, the instruments, the books and charts and drawings, in the middle of the floor under the dome, pour oil on the heap, and set fire to that. The flames spread to the wooden beams of the big telescope frame and to the clockwork mechanisms. Villagers watching from the foot of the hill saw the dome, whitish against the green evening sky, shudder and turn, first in one direction then in the other, while a black and yellow smoke full of sparks gushed from the oblong slit: an ugly and uncanny thing to see.

It was getting dark, stars were showing in the east. Orders were shouted. The soldiers came down the road in single file, dark men in dark harness, silent.

The villagers at the foot of the hill stayed on after the soldiers had gone. In a life without change or breadth a fire is as good as a festival. They did not climb the hill, and as the night grew full dark, they drew closer together. After a while they began to return to their villages. Some looked back over their shoulders at the hill, where nothing moved. The stars turned slowly behind the black beehive of the dome, but it did not turn to follow them.

About an hour before daybreak a man rode up the steep zigzag, dismounted by the ruins of the workshops, and approached the dome on foot. The door had been smashed in. Through it a reddish haze of light was visible, very dim, coming from a massive beam that had fallen and had smoldered all night inward to its core. A hanging, sour smoke thickened the air inside the dome. A tall figure moved there and its shadow moved with it, cast upward on the murk. Sometimes it stooped, or stopped, then blundered slowly on.

The man at the door said, “Guennar! Master Guennar!”

The man in the dome stopped still, looking toward the door. He had just picked up something from the mess of wreckage and halfburnt stuff on the floor. He put this object mechanically into his coat pocket, still peering at the door. He came toward it. His eyes were red and swollen almost shut, he breathed harshly in gasps, his hair and clothes Were scorched and smeared with black ash.

“Where were you?”

The man in the dome pointed vaguely at the ground.

“There’s a cellar? That’s where you were during the fire? By God! Gone to ground! I knew it, I knew you’d be here.” Bord laughed, a little crazily, taking Guennar’s arm. “Come on. Come out of there, for the love of God. There’s light in the east already.”

The astronomer came reluctantly, looking not at the grey east but back up at the slit in the dome, where a few stars burned clear. Bord pulled him outside, made him mount the horse, and then, bridle in hand, set off down the hill leading the horse at a fast walk.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Orbit 14»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Orbit 14» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Orbit 14» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.