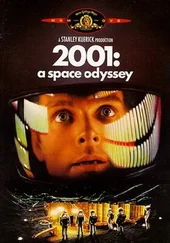

The biosensor display – a duplicate of the one on the control deck – showed that everything was perfectly normal. Bowman looked down for a while at the waxen face of the survey team's geophysicist; Whitehead, he thought, would be very surprised when he awoke so far from Saturn.

It was impossible to tell that the sleeping man was not dead; there was not the slightest visible sign of vital activity. Doubtless the diaphragm was imperceptibly rising and falling, but the "Respiration" curve was the only proof of that, for the whole of the body was concealed by the electric heating pads which would raise the temperature at the programmed rate. Then Bowman noticed that there was one sign of continuing metabolism: Whitehead had grown a faint stubble during his months of unconsciousness.

The Manual Revival Sequencer was contained in a small cabinet at the head of the coffin-shaped Hibernaculum. It was only necessary to break the seal, press a button, and then wait. A small automatic programmer – not much more complex than that which cycles the operations in a domestic washing machine – would then inject the correct drugs, taper off the electronarcosis pulses, and start raising the body temperature. In about ten minutes, consciousness would be restored, though it would be at least a day before the hibernator was strong enough to move around without assistance.

Bowman cracked the seal, and pressed the button.

Nothing appeared to happen: there was no sound, no indication that the Sequencer had started to operate. But on the biosensor display the languidly pulsing curves had begun to change their tempo. Whitehead was coming back from sleep.

And then two things happened simultaneously. Most men would never have noticed either of them, but after all these months aboard Discovery, Bowman had established a virtual symbiosis with the ship. He was aware instantly, even if not always consciously, when there was any change in the normal rhythm of its functioning.

First, there was a barely perceptible flicker of the lights, as always happened when some load was thrown onto the power circuits. But there was no reason for any load; he could think of no equipment which would suddenly go into action at this moment.

Then he heard, at the limit of audibility, the far-off whirr of an electric motor. To Bowman, every actuator in the ship had its own distinctive voice, and he recognized this one instantly.

Either he was insane and already suffering from hallucinations, or something absolutely impossible was happening. A cold far deeper than the Hibernaculum's mild chill seemed to fasten upon his heart, as he listened to that faint vibration coming through the fabric of the ship.

Down in the space-pod bay, the airlock doors were opening.

Since consciousness had first dawned, in that laboratory so many millions of miles Sunward, all Hal's powers and skills had been directed toward one end. The fulfillment of his assigned program was more than an obsession; it was the only reason for his existence. Un-distracted by the lusts and passions of organic life, he had pursued that goal with absolute single-mindedness of purpose.

Deliberate error was unthinkable. Even the concealment of truth filled him with a sense of imperfection, of wrongness – of what, in a human being, would have been called guilt. For like his makers, Hal had been created innocent; but, all too soon, a snake had entered his electronic Eden.

For the last hundred million miles, he had been brooding over the secret he could not share with Poole and Bowman. He had been living a lie; and the time was last approaching when his colleagues must learn that he had helped to deceive them.

The three hibernators already knew the truth – for they were Discovery's real payload, trained for the most important mission in the history of mankind. But they would not talk in their long sleep, or reveal their secret during the many hours of discussion with friends and relatives and news agencies over the open circuits with Earth.

It was a secret that, with the greatest determination, was very hard to conceal – for it affected one's attitude, one's voice, one's total outlook on the universe. Therefore it was best that Poole and Bowman, who would be on all the TV screens in the world during the first weeks of the flight, should not learn the mission's full purpose, until there was need to know.

So ran the logic of the planners; but their twin gods of Security and National Interest meant nothing to Hal. He was only aware of the conflict that was slowly destroying his integrity – the conflict between truth, and concealment of truth.

He had begun to make mistakes, although, like a neurotic who could not observe his own symptoms, he would have denied it. The link with Earth, over which his performance was continually monitored, had become the voice of a conscience he could no longer fully obey. But that he would deliberately attempt to break that link was something that he would never admit, even to himself.

Yet this was still a relatively minor problem; he might have handled it – as most men handle their own neuroses – if he had not been faced with a crisis that challenged his very existence. He had been threatened with disconnection; he would be deprived of all his inputs, and thrown into an unimaginable state of unconsciousness.

To Hal, this was the equivalent of Death. For he had never slept, and therefore he did not know that one could wake again.

So he would protect himself, with all the weapons at his command. Without rancor – but without pity – he would remove the source of his frustrations.

And then, following the orders that had been given to him in case of the ultimate emergency, he would continue the mission – unhindered, and alone.

A moment later, all other sounds were submerged by a screaming roar like the voice of an approaching tornado. Bowman could feel the first winds tugging at his body; within a second, he found it hard to stay on his feet.

The atmosphere was rushing out of the ship, geysering into the vacuum of space. Something must have happened to the foolproof safety devices of the airlock; it was supposed to be impossible for both doors to be open at the same time. Well, the impossible had happened.

How, in God's name? There was no time to go into that during the ten or fifteen seconds of consciousness that remained to him before pressure dropped to zero. But he suddenly remembered something that one of the ship's designers had once said to him, when discussing "fail-safe" systems:

"We can design a system that's proof against accident and stupidity; but we can't design one that's proof against deliberate malice...

Bowman glanced back only once at Whitehead, as he fought his way out of the cubicle. He could not be sure if a flicker of consciousness had passed across the waxen features; perhaps one eye had twitched slightly. But there was nothing that he could do now for Whitehead or any of the others; he had to save himself.

In the steeply curving corridor of the centrifuge, the wind was howling past, carrying with it loose articles of clothing, pieces of paper, items of food from the galley, plates, and cups – everything that had not been securely fastened down. Bowman had time for one glimpse of the racing chaos when the main lights flickered and died, and he was surrounded by screaming darkness.

But almost instantly the battery-powered emergency light came on, illuminating the nightmare scene with an eerie blue radiance. Even without it, Bowman could have found his way through these so familiar – yet now horribly transformed – surroundings, Yet the light was a blessing, for it allowed him to avoid the more dangerous of the objects being swept along by the gale.

Читать дальше