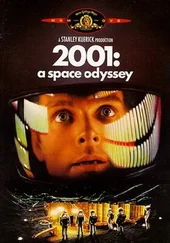

He had only part of its track, but when the computer projected it on the Planet Situation Board, it was as clear and unmistakable as a vapor trail across a cloudless sky, or a single line of footprints over a field of virgin snow.

Some immaterial pattern of energy, throwing off a spray of radiation like the wake of a racing speedboat, had leaped from the face of the Moon, and was heading out toward the stars.

The ship was still only thirty days from Earth, yet David Bowman sometimes found it hard to believe that be had ever known any other existence than the closed little world of Discovery. All his years of training, all his earlier missions to the Moon and Mars, seemed to belong to another man, in another life.

Frank Poole admitted to the same feelings, and had sometimes jokingly regretted that the nearest psychiatrist was the better part of a hundred million miles away. But this sense of isolation and estrangement was easy enough to understand, and certainly indicated no abnormality. In the fifty years since men had ventured into space, there had never been a mission quite like this.

It had begun, five years ago, as Project Jupiter – the first manned round trip to the greatest of the planets. The ship was nearly ready for the two-year voyage when, somewhat abruptly, the mission profile had been changed.

Discovery would still go to Jupiter; but she would not stop there. She would not even slacken speed as she raced through the far-ranging Jovian satellite system. On the contrary – she would use the gravitational field of the giant world us a sling to cast her even farther from the Sun. Like a comet, she would streak on across the outer reaches of the solar system to her ultimate goal, the ringed glory of Saturn. And she would never return.

For Discovery, it would be a one-way trip – yet her crew had no intention of committing suicide. If all went well, they would be back on Earth within seven years – five of which would pass like a flash in the dreamless sleep of hibernation, while they awaited rescue by the still unbuilt Discovery II.

The word "rescue" was carefully avoided in all the Astronautics Agency's statements and documents; it implied some failure of planning, and the approved jargon was "re-acquisition." If anything went really wrong, there would certainly be no hope of rescue, almost a billion miles from Earth.

It was a calculated risk, like all voyages into the unknown. But half a century of research had proved that artificially induced human hibernation was perfectly safe, and it had opened up new possibilities in space travel. Not until this mission, however, had they been exploited to the utmost.

The three members of the survey team, who would not be needed until the ship entered her final orbit around Saturn, would sleep through the entire outward flight. Tons of food and other expendables would thus be saved; almost as important, the team would be fresh and alert, and not fatigued by the ten-month voyage, when they went into action.

Discovery would enter a parking orbit around Saturn, becoming a new moon of the giant planet. She would swing back and forth along a two-million-mile ellipse that took her close to Saturn, and then across the orbits of all its major moons. They would have a hundred days in which to map and study a world with eighty times the area of Earth, and surrounded by a retinue of at least fifteen known satellites – one of them as large as the planet Mercury.

There must be wonders enough here for centuries of study; the first expedition could only carry out a preliminary reconnaissance. All that it found would be radioed back to Earth; even if the explorers never returned, their discoveries would not be lost.

At the end of the hundred days, Discovery would close down. All the crew would go into hibernation; only the essential systems would continue to operate, watched over by the ship's tireless electronic brain. She would continue to swing around Saturn, on an orbit now so well determined that men would know exactly where to look for her a thousand years hence. But in only five years, according to present plans, Discovery II would come. Even if six or seven or eight years elapsed, her sleeping passengers would never know the difference. For all of them, the clock would have stopped as it had stopped already for Whitehead, Kaminski, and Hunter.

Sometimes Bowman, as First Captain of Discovery, envied his three unconscious colleagues in the frozen peace of the Hibernaculum. They were free from all boredom and all responsibility; until they reached Saturn, the external world did not exist.

But that world was watching them, through their bio-sensor displays. Tucked inconspicuously away among the massed instrumentation of the Control Deck were five small panels marked Hunter, Whitehead, Kaminski, Poole, Bowman. The last two were blank and lifeless; their time would not come until a year from now. The others bore constellations of tiny green lights, announcing that everything was well; and on each was a small display screen across which sets of glowing lines traced the leisurely rhythms that indicated pulse, respiration, and brain activity.

There were times when Bowman, well aware how unnecessary this was – for the alarm would sound instantly if anything was wrong – would switch over to audio output. He would listen, half hypnotized, to the infinitely slow heartbeats of his sleeping colleagues, keeping his eyes fixed on the sluggish waves that marched in synchronism across the screen.

Most fascinating of all were the EEG displays – the electronic signatures of three personalities that had once existed, and would one day exist again. They were almost free from the spikes and valleys, the electrical explosions that marked the activity of the waking brain – or even of the brain in normal sleep. If there was any wisp of consciousness remaining, it was beyond the reach of instruments, and of memory.

This last fact Bowman knew from personal experience. Before he was chosen for this mission, his reactions to hibernation had been tested. He was not sure whether he had lost a week of his life – or whether he had postponed his eventual death by the same amount of time.

When the electrodes had been attached to his forehead, and the sleep-generator had started to pulse, he had seen a brief display of kaleidoscopic patterns and drifting stars. Then they had faded, and darkness had engulfed him. He had never felt the injections, still less the first touch of cold as his body temperature was reduced to only a few degrees above freezing.

He awoke, and it seemed that he had scarcely closed his eyes. But he knew that was an illusion; somehow, he was convinced that years had really passed.

Had the mission been completed? Had they already reached Saturn, carried out their survey, and gone into hibernation? Was Discovery II here, to take them back to Earth?

He lay in a dreamlike haze, utterly unable to distinguish between real and false memories. He opened his eyes, but there was little to see except a blurred constellation of lights which puzzled him for some minutes.

Then he realized that he was looking at the indicator lamps on a Ship Situation Board, but it was impossible to focus on them. He soon gave up the attempt.

Warm air was blowing across him, removing the chill from his limbs. There was quiet, but stimulating, music welling from a speaker behind his head. It was slowly growing louder and louder.

Then a relaxed, friendly – but he knew computer generated – voice spoke to him.

"You are becoming operational, Dave. Do not get up or attempt any violent movements. Do not try to speak."

Do not get up! thought Bowman. That was funny. He doubted if he could wriggle a finger. Rather to his surprise, he found that he could.

Читать дальше