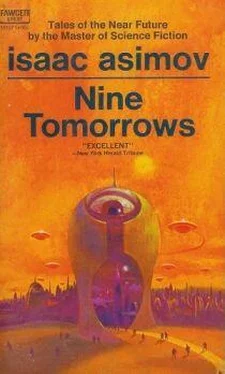

Isaac Asimov - Nine Tomorrows

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Isaac Asimov - Nine Tomorrows» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1970, Издательство: Fawcett Crest, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nine Tomorrows

- Автор:

- Издательство:Fawcett Crest

- Жанр:

- Год:1970

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nine Tomorrows: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nine Tomorrows»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nine Tomorrows — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nine Tomorrows», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Mercury Observatory, closest to the sun, perched at Mercury's north pole, where the terminator moved scarcely at all, and the sun was fixed on the horizon and could be studied in the minutest detail.

Ceres Observatory, newest, most modern, with its range extending from Jupiter to the outermost galaxies.

There were disadvantages, of course. With interplanetary travel still difficult, leaves would be few, anything like normal life virtually impossible, but this was a lucky generation. Coming scientists would find the fields of knowledge well-reaped and, until the invention of an interstellar drive, no new horizon as capacious as this one would be opened.

Each of these lucky four, Talliaferro, Ryger, Kaunas, and Villiers, was to be in the position of a Galileo, who by owning the first real telescope, could not point it anywhere in the sky without making a major discovery.

But then Romero Villiers had fallen sick and it was rheumatic fever. Whose fault was that? His heart had been left leaking and limping.

He was the most brilliant of the four, the most hopeful, the most intense-and he could not even finish his schooling and get his doctorate.

Worse than that, he could never leave Earth; the acceleration of a spaceship's take-off would kill him.

Talliaferro was marked for the Moon, Ryger for Ceres, Kaunas for Mercury. Only Villiers stayed behind, a life-prisoner of Earth.

They had tried telling their sympathy and Villiers had rejected it with something approaching hate. He had railed at them and cursed them. When Ryger lost his temper and lifted his fist, Villiers had sprung at him, screaming, and had broken Ryger's nose.

Obviously Ryger hadn't forgotten that, as he caressed his nose gingerly with one finger.

Kaunas's forehead was an uncertain washboard of wrinkles. "He's at the Convention, you know. He's got a room in the hotel-405."

"I won't see him," said Ryger.

"He's coming up here. He said he wanted to see us. I thought-He said nine. He'll be here any minute."

"In that case," said Ryger, "if you don't mind, I'm leaving." He rose.

Talliaferro said, "Oh, wait a while. What's the harm in seeing him?"

"Because there's no point. He's mad."

"Even so. Let's not be petty about it. Are you afraid of him?"

"Afraid!" Ryger looked contemptuous.

"Nervous, then. What is there to be nervous about?"

"I'm not nervous," said Ryger.

"Sure you are. We all feel guilty about him, and without real reason. Nothing that happened was our fault." But he was speaking defensively and he knew it.

And when, at that point, the door signal sounded, all three jumped and turned to stare uneasily at the barrier that stood between themselves and Villiers.

The door opened and Romero Villiers walked in. The others rose stiffly to greet him, then remained standing in embarrassment, without one hand being raised.

He stared them down sardonically.

He's changed, thought Talliaferro.

He had. He had shrunken in almost every dimension. A gathering stoop made him seem even shorter. The skin of his scalp glistened through thinning hair, the skin on the back of his hands was ridged crookedly with bluish veins. He looked ill. There seemed nothing to link him to the memory of the past except for his trick of shading his eyes with one hand when he stared intently and, when he spoke, the even, controlled baritone of his voice.

He said, "My friends! My space-trotting friends! We've lost touch."

Talliaferro said, "Hello, Villiers."

Villiers eyed him. "Are you well?"

"Well enough."

"And you two?"

Kaunas managed a weak smile and a murmur. Ryger snapped, "All right, Villiers. What's up?"

"Ryger, the angry man," said Villiers. "How's Ceres?"

"It was doing well when I left. How's Earth?"

"You can see for yourself," but Villiers tightened as he said that.

He went on, "I am hoping that the reason all three of you have come to the Convention is to hear my paper day after tomorrow."

"Your paper? What paper?" asked Talliaferro.

"I wrote you all about it. My method of mass-transference."

Ryger smiled with one corner of his mouth. "Yes, you did. You didn't say anything about a paper, though, and I don't recall that you're listed as one of the speakers. I would have noticed it if you had been."

"You're right. I'm not listed. Nor have I prepared an abstract for publication."

Villiers had flushed and Taliaferro said soothingly, "Take it easy, Villiers. You don't look well."

Villiers whirled on him, lips contorted. "My heart's holding out, thank you."

Kaunas said, "Listen, Villiers, if you're not listed or abstracted-"

"You listen. I've waited ten years. You have the jobs in space and I have to teach school on Earth, but I'm a better man than any of you or all of you."

"Granted-" began Talliaferro.

"And I don't want your condescension either. Mandel witnessed it. I suppose you've heard of Mandel. Well, he's chairman of the astronautics division at the Convention and I demonstrated mass-transference for him. It was a crude device and it burnt out after one use but-Are you listening?"

"We're listening," said Ryger coldly, "for what that counts."

"He'll let me talk about it my way. You bet he will. No warning. No advertisement. I'm going to spring it at them like a bombshell. When I give them the fundamental relationships involved it will break up the Convention. They'll scatter to their home labs to check on me and build devices. And they'll find it works. I made a live mouse disappear at one spot in my lab and appear in another. Mandel witnessed it."

He stared at them, glaring first at one face, then at another. He said, "You don't believe me, do you?"

Ryger said, "If you don't want advertisement, why do you tell us?"

"You're different. You're my friends, my classmates. You went out into space and left me behind."

"That wasn't a matter of choice," objected Kaunas in a thin, high voice.

Villiers ignored that. He said, "So I want you to know now. What will work for a mouse will work for a human. What will move something ten feet across a lab will move it a million miles across space. I'll be on the Moon, and on Mercury, and on Ceres and anywhere I want to go. I'll match every one of you and more. And I'll have done more for astronomy just teaching school and thinking, than all of you with your observatories and telescopes and cameras and spaceships."

"Well," said Talliaferro, "I'm pleased. More power to you. May I see a copy of the paper?"

"Oh, no." Villiers' hands clenched close to his chest as though he were holding phantom sheets and shielding them from observation. "You wait like everyone else. There's only one copy and no one will see it till I'm ready. Not even Mandel."

"One copy," cried Talliaferro. "If you misplace it-"

"I won't. And if I do, it's all in my head."

"If you-" Talliaferro almost finished that sentence with "die" but stopped himself. Instead, he went on after an almost imperceptible pause, "-have any sense, you'll scan it at least. For safety's sake."

"No," said Villiers, shortly. "You'll hear me day after tomorrow. You'll see the human horizon expanded at one stroke as it never has been before."

Again he stared intently at each face. "Ten years," he said. "Good-by."

"He's mad," said Ryger explosively, staring at the door as though Villiers were still standing before it.

"Is he?" said Talliaferro thoughtfully. "I suppose he is, in a way. He hates us for irrational reasons. And, then, not even to scan his paper as a precaution-"

Talliaferro fingered his own small scanner as he said that. It was just a neutrally colored, undistinguished cylinder, somewhat thicker and somewhat shorter than an ordinary pencil. In recent years, it had become the hallmark of the scientist, much as the stethoscope was that of the physician and the micro-computer that of the statistician. The scanner was worn in a jacket pocket, or clipped to a sleeve, or slipped behind the ear, or swung at the end of a string.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nine Tomorrows»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nine Tomorrows» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nine Tomorrows» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.