“Soft pipes, play on,” I murmured huskily.

“Well, maybe you can find some neat way to die, too,” said Newt.

It was a Bokononist thing to say.

I blurted out my dream of climbing Mount McCabe with some magnificent symbol and planting it there. I took my hands from the wheel for an instant to show him how empty of symbols they were. “But what in hell would the right symbol be , Newt? What in hell would it be? ” I grabbed the wheel again. “Here it is, the end of the world; and here I am, almost the very last man; and there it is, the highest mountain in sight. I know now what my karass has been up to, Newt. It’s been working night and day for maybe half a million years to get me up that mountain.” I wagged my head and nearly wept. “But what, for the love of God, is supposed to be in my hands?”

I looked out of the car window blindly as I asked that, so blindly that I went more than a mile before realizing that I had looked into the eyes of an old Negro man, a living colored man, who was sitting by the side of the road.

And then I slowed down. And then I stopped. I covered my eyes.

“What’s the matter?” asked Newt.

“I saw Bokonon back there.”

He was sitting on a rock. He was barefoot. His feet were frosty with ice-nine . His only garment was a white bedspread with blue tufts. The tufts said Casa Mona. He took no note of our arrival. In one hand was a pencil. In the other was paper.

“Bokonon?”

“Yes?”

“May I ask what you’re thinking?”

“I am thinking, young man, about the final sentence for The Books of Bokonon . The time for the final sentence has come.”

“Any luck?”

He shrugged and handed me a piece of paper.

This is what I read:

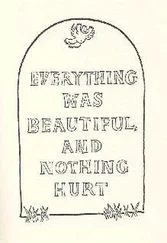

If I were a younger man, I would write a history of human stupidity; and I would climb to the top of Mount McCabe and lie down on my back with my history for a pillow; and I would take from the ground some of the blue-white poison that makes statues of men; and I would make a statue of myself, lying on my back, grinning horribly, and thumbing my nose at You Know Who.