"He doesn't know anything about business," I said.

"How can he still be so rich, if he doesn't know anything about business?" she said.

"His brother runs everything," I said.

"I wish my father had somebody to run everything for him," she said.

I knew that things were going so badly for her father that her brother, my roommate, had decided to drop out of school at the end of the semester. He would never go back to school, either. He would take a job as an orderly in a tuberculosis sanitarium, and himself contract tuberculosis. That would keep him out of the armed forces in the Second World War. He would work as a welder in a Boston shipyard, instead. I would lose touch with him. Sarah, whom I see regularly again, told me that he died of a heart attack in Nineteen-hundred and Sixty-five — in a cluttered little welding shop he ran single-handed in the village of Sandwich, or Cape Cod.

His name was Radford Alden Wyatt. He never married. According to Sarah, he had not bathed in years.

"Shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations," as the saying goes.

In the case of the Wyatts, actually, it was more like shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in ten generations. They had been richer than most of their neighbors for at least that long. Sarah's father was now selling off at rock-bottom prices all the treasures his ancestors had accumulated — English pewter, silver by Paul Revere, paintings of Wyatts as sea captains arid merchants and preachers and lawyers, treasures from the China Trade.

"It's so awful to see my father so low all the time," said Sarah. "Is your father low, too?"

She was speaking of my fictitious father, the curator of Mr. McCone's art collection. I could see him quite clearly then. I can't see him at all now. "No," I said,

"You're so lucky," she said.

"I guess so," I said. My real father was in fact in easy circumstances. My mother and he had been able to bank almost every penny they made, and the bank they put their money in had not failed.

"If only people wouldn't care so much about money," she said. "I keep telling father that I don't care about it. I don't care about not going to Europe anymore. I hate school. I don't want to go there anymore. I'm not learning anything. I'm glad we sold our boats. I was bored with them, anyway. I don't need any clothes. I have enough clothes to last me a hundred years. He just won't believe me. 'I've let you down. I've let everybody down,' he says."

Her father, incidentally, was an inactive partner in the Wyatt Clock Company. This did not limit his liability in the radium-poisoning case, but his principal activity in the good old days had been as the largest yacht broker in Massachusetts. That business was utterly shot in Nineteen-hundred and Thirty-one, of course. And it, too, in the process of dying, left him with what he once described to me as " . . . a pile of worthless accounts-receivable as high as Mount Washington, and a pile of bills as high as Pike's Peak."

He, too, was a Harvard man — the captain of the undefeated swimming team of Nineteen-hundred and Eleven. After he lost everything, he would never work again. He would be supported by his wife, who would operate a catering service out of their home. They would die penniless.

So I am not the first Harvard man who had to be supported by his wife.

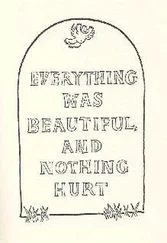

Peace.

Sarah said to me at the Arapahoe that she was sorry to be so depressing, that she knew we were supposed to have fun. She said she would really try to have fun.

It was then that the waiter, shepherded by the owner, delivered the first course, specified by Mr. McCone in Cleveland, so far away. It was a half-dozen Cotuit oysters for each of us. I had never eaten an oyster before.

"Bon appetit!" said the owner. I was thrilled. I had never had anybody say that to me before. I was so pleased to understand something in French without the help of an interpreter. I had studied French for four years in a Cleveland public high school, by the way, but I never found anyone who spoke the dialect I learned out there. It may have been French as it was spoken by Iroquois mercenaries in the French and Indian War.

Now the Gypsy violinist came to our table. He played with all possible hypocrisy and brilliance, in the frenzied expectation of a tip. I remembered that Mr. McCone had told me to tip lavishly. I had not so far tipped anyone. So I got out my billfold surreptitiously while the music was still going on, and I took from it what I thought was a one-dollar bill. A common laborer in those days would have worked ten hours for a dollar. I was about to make a lavish tip. Fifty cents would have put me quite high up in the spendthrift class. I wadded up the bill in my right hand, so as to tip with the quick grace of a magician when the music stopped.

The trouble was this: It wasn't a one-dollar bill. It was a twenty-dollar bill.

I blame Sarah somewhat for this sensational mistake. While I was taking the money from the billfold, she was satirizing sexual love again, pretending that the music was filling her with lust. She undid my necktie, which I would be unable to retie. It had been tied by the mother of a friend with whom I was staying. Sarah kissed the tips of two of her fingers passionately, and then pressed those fingers to my white collar, leaving a smear of lipstick there.

Now the music stopped. I smiled my thanks. Diamond Jim Brady, reincarnated as the demented son of a Cleveland chauffeur, handed the Gypsy a twenty-dollar bill.

The Gypsy was quite suave at first, imagining that he had received a dollar.

Sarah, believing it to be a dollar, too, thought I had tipped much too much. "Good God," she said.

But then, perhaps to taunt Sarah with the bill that she would have liked me to take back, but which was now his, all his, the Gypsy unfolded the wad, so that its astronomical denomination became apparent to all of us for the first time. He was as aghast as we were.

And then, being a Gypsy, and hence one microsecond more cunning about money than we were, he darted out of the restaurant and into the night. I wonder to this day if he ever came back for his fiddlecase.

But imagine the effect on Sarah!

She thought I had done it on purpose, that I was stupid enough to imagine that this would be a highly erotic event for her. Never have I been loathed so much.

"You inconceivable twerp," she said. Most of the speeches in this book are necessarily fuzzy reconstructions — but when I assert that Sarah Wyatt called me an "inconceivable twerp," that is exactly what she said.

To give an extra dimension to the scolding she gave me: The word "twerp" was freshly coined in those days, and had a specific definition — it was a person, if I may be forgiven, who bit the bubbles of his own farts in a bathtub.

"You unbelievable jerk," she said. A "jerk" was a person who masturbated too much. She knew that. She knew all those things.

"Who do you think you are?" she said. "Or, more to the point, who do you think I am? I may be a dumb toot," she said, "but how dare you think I am such a dumb toot that I would think what you just did was glamorous?"

This was the lowest point in my life, possibly. I felt worse then than I did when I was put in prison — worse, even, than when I was turned loose again. I may have felt worse then, even, than when I set fire to the drapes my wife was about to deliver to a client in Chevy Chase.

"Kindly take me home," Sarah Wyatt said to me. We left without eating, but not without paying. I could not help myself: I cried all the way home.

I told her brokenly in the taxicab that nothing about the evening had been my own idea, that I was a robot invented and controlled by Alexander Hamilton McCone. I confessed to being half-Polish and half-Lithuanian and nothing but a chauffeur's son who had been ordered to put on the clothing and airs of a gentleman. I said I wasn't going back to Harvard, and that I wasn't even sure I wanted to live anymore.

Читать дальше