Dane said, “Tong Asia enters the plot again.”

“You got any better ideas?” Noel retorted. “Or do you want to vote for a Martian sandman too?”

“That makes six men we’ve lost. Six out of 125,” Heileman said. “Every now and then we lose a man. You understand what actually kills each one of them, but you wouldn’t ever have expected it. Something just happens. Every now and then another guy gets it. When you least expect it and for some cause you never could have foreseen or prevented First it was Houck. Dane and Wertz find him dead and flat on his back in the lichens. How or why, nobody can guess. Then Dr. Pembroke gets off his bat and shoots himself. Then the lichens go crazy in Wertz’s lab and Spear and Gonzales get it. Who could have thought of that? Yet they get it. Now Beemis and Jackson. That makes six of us. None of them dead in any way you might have expected, like a Martian snake biting one of us. If there had been any snakes, I mean. Still, at least you would understand something like a snake possibly living here. Or an accident of some kind here with the equipment. Or an infection by some unknown disease here. But nothing like that! Nothing simple like that! It’s so irrational that I damn near got to think maybe something is going on with this Tong Asia business like Noel said. Without something damn funny going on, none of these guys getting killed makes any sense at all, except maybe the ones that got caught in the lichen explosion.”

Dane couldn’t deny him that. Some primary pieces were missing, he thought as he swarmed through the hatch into the observation chamber.

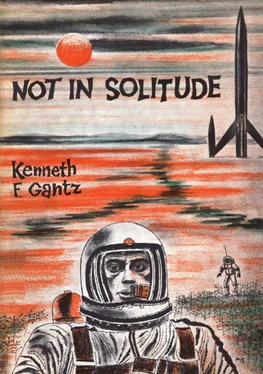

He looked out at the sterile plains of Mars and the elongated shadow of the spacecraft pacing off toward the east over the red desert like a problem in geometry. Would they ever see Earth again? If they did, would men ever come again to Mars?

In a few minutes possibly the last night on Mars would begin. No communication with the Martians had yet been achieved later than an hour or two after sunset. None before ten in the morning. Opportunity was fleeting fast. Dane went to the switch key. He began to send in the number code.

Men not know Martians, he managed in the rough-hewn symbol language . Martians exist? Men know not. Men know two plus two equals four. Men know Martians not equal zero. What Martians equal?

He repeated that much twice and then sent, Martians come spacecraft. Know is good. Martians come spacecraft. Martians equal what? Martians come spacecraft. Men know. Good. Good.

He saw the photo plane table flicker with the beginning of a reply. Exulting, he watched it finally settle into the familiar symbols. He read: Martians are one. One is good . Men and Martians are many. Many is bad. Men die. Men are not. Martians are one. One is good. Martians come spacecraft. Men die. Spacecraft die. Men and spacecraft not exist. Equals good. Martians are one. One is good.

It was like a chant at the jungle’s edge. From the flicker of cold light against the opal glass hate burned unmistakably through the halting tirade. Dane leaped for the switch key. Bigod, they had to understand. They had to come in peace and be received in peace.

Simultaneously with his clutch over the knob a clamor of metal burst around him. He fought it stupidly, before he realized the alarm gong overhead was clanging in his ear noise stopped abruptly, and he heard Major Noel’s impersonal authority on the speaker. “Battle stations. All crew to battle stations.”

Dane ran to the ports. “You see anything?”

Humphries shook his head. “Huh-uh.”

If anything moved under the fading light it was too small or too distant to be visible.

Through the open hatch rose a hubbub of excited voices, hurrying footsteps, and whine of motors—the jolting staccato of the guns clearing. “They sure as hell spotted something,” Humphries sang out. “Take a look on the table. I gotta stay here at my post.”

Of course. The plane table.

The opal glass was dead! A thought stung. It’s been knocked out. The Martians have blinded us. He jerked at the switch key. It was off.

Lieutenant Yudin thrust his head through the hatch “What’s up? I was asleep,” he added.

“I don’t know,” Dane answered him. “Unless…”

The intercom squawked again. Then it said, “Stand by at all stations. Lichens are advancing rapidly. Point of closest approach is 112 degrees. Repeat, 112 degrees. Range 2600 yards. Repeat, 2600 yards.”

Dane whistled. “That’s fourteen hundred yards closer.” But he couldn’t have killed the plane tables more than ten minutes by the messages, he thought guiltily.

On the Plane table the line of the lichen peninsula ran straight across the sand plain toward the spacecraft, a finger of light that crawled purposively across the grid lines

Dane put the dividers on it. “It’s making a hundred yards a minute. A good hundred yards! You ought to be able to see it through the port by now,” he called to Humphries

Humphries turned to Lieutenant Yudin. “No, sir. It’s too dark now.”

The last slice of the small sun floated over the low hills in the west wrapping itself in smallish yellow blaze. They strained to see through the thick glassite ports, but the light was almost gone. To the east the land had disappeared under starless night. The rotating guard beacon strained weakly at the twilight.

In five minutes the lichens had marched another measured six hundred yards. The range had closed to two thousand yards.

“They’re going out!” Humphries exclaimed. “They’re taking out the flamethrowers.”

Dane counted eleven pressure-suited figures on the sand below, looking down at them past the bulge of the spherical hull. They seemed to stand almost under the shelter of the curving sides. All but one had the cylinders of the self-oxydizing flame ejectors strapped behind their shoulders. Two one-man flame-throwing tanks darted from under the spacecraft, their armor red with the dust they kicked up in motionless clouds. Then the little party spread apart and deployed in a bowed line facing the oncoming lichens.

Abruptly Dane left the port and yanked at the exit hatch. “See you later,” he said.

THE AIRLOCK guard observed him indifferently. Dane came the rest of the way down the ladder with his pressure suit and helmet. When the man saw him start hooking in the radio equipment, his mouth line straightened.

“Not allowed to go outside,” he Georgia-drawled. “Nobody supposed to.”

“I am,” Dane told him. “I represent the almighty press. Amalgamated, that is.”

“Nobody allowed outside,” the guard reiterated. He shifted easily on his feet and peered out the port. “Fire party out there right now, besides.”

Dane pushed a leg into the heavy, articulated casing. I am on my master’s business. The public must be told. See all, hear all, tell all, know nothing. That’s us. Molders of public opinion. Have to be Johnny-on-the-spot, and all that.

“Mebbe so,” the man grunted. “You have to do your looking from here, though.” He brightened a little. “Unless you got a pass. You gotta pass?”

“That’s a wonderful idea,” Dane said. “Why don’t you call the command post and tell them John Dane wants to go out with the fire party on press duty?”

The guard allowed he didn’t care, one way or the other, but he picked up the phone and spoke briefly. “Yeah,” he said “It’s Dr. Dane.” Out of the corner of his mouth he said, “They’re checkin’ with Major Noel. He’s outside” After a minute he said, “Yeah. I’ll tell him.”

He hung up. “Sergeant Peeney says the major says okay, but you gotta stay behind the fire party. That’s so you don’t get hurt,’” he threw in “Case they light up the flame throwers”

Читать дальше