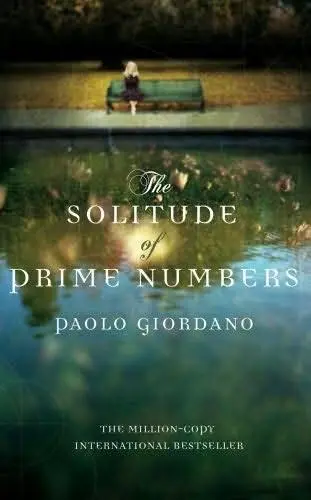

Paolo Giordano

The Solitude of Prime Numbers

Translation copyright (c) Shaun Whiteside, 2009

Originally published in Italian as La Solitudine dei Numberi Primi by Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, Milan. Copyright (c) 2008 Arnoldo Mondadori Editore S.p.A.

To Eleonora,

because in silence

I promised it to you

This book wouldn't have existed without Raffaella Lops.

I would like to thank, in no particular order, Antonio Franchini, Joy Terekiev, Mario Desiati, Giulia Ichino, Laura Cerutti, Cecilia Giordano, my parents, Giorgio Mila, Roberto Castello, Emiliano Amato, Pietro Grossi, and Nella Re Rebaudengo. Each of them knows why.

Her old aunt's elaborately trimmed dress was a perfect fit for Sylvie's slender figure, and she asked me to lace it up for her. "The sleeves are plain; how ridiculous!" she said.

– Gerard de Nerval, Sylvie, 1853

1983

Alice Della Rocca hated ski school. She hated getting up at seven-thirty, even during Christmas vacation. She hated her father staring at her over breakfast, his leg dancing nervously under the table as if to say hurry up, get a move on. She hated the woolen tights that made her thighs itch, the mittens that kept her from moving her fingers, the helmet that squashed her cheeks, and the big, too tight boots that made her walk like a gorilla.

"Are you going to drink that milk or not?" her father insisted again.

Alice gulped down three inches of boiling milk, burning her tongue, throat, and stomach.

"Good, today you can show us what you're really made of."

What's that? Alice wondered.

He shoved her out the door, mummified in a green ski suit dotted with badges and the fluorescent logos of the sponsors. It was 14 degrees and a gray fog enveloped everything. Alice felt the milk swirling around in her stomach as she sank into the snow. Her skis were over her shoulder, because you had to carry your skis yourself until you got good enough for someone to carry them for you.

"Keep the tips facing forward or you'll kill someone," her father said.

At the end of the season the Ski Club gave you a pin with little stars on it. A star a year, from when you were four years old and just tall enough to slip the little disk of the ski lift between your legs until you were nine and you managed to grab the disk all by yourself. Three silver stars and then another three in gold: a pin a year, a way of saying you'd gotten a little better, a little closer to the races that terrified Alice. She was already worried about them even though she had only three stars.

They were to meet at the ski lift at eight-thirty sharp, right when it opened. The other kids were already there, standing like little soldiers in a loose circle, bundled up in their uniforms, numb with sleep and cold. They planted their ski poles in the snow and wedged the grips in their armpits. With their arms dangling, they looked like scarecrows. No one felt like talking, least of all Alice. Her father rapped twice on her helmet, too hard, as if trying to pound her into the snow.

"Pull out all the stops," he said. "And remember: keep your body weight forward, okay? Body weight forward."

"Body weight forward," echoed the voice in Alice's head.

Then he walked away, blowing into his cupped hands. He'd soon be home again, reading the paper in the warmth of their house. Two steps and the fog swallowed him up.

Alice clumsily dropped her skis on the ground and banged her boots with a ski pole to knock off the clumps of snow. If her father had seen her he would have slapped her right there, in front of everyone.

She was already desperate for a pee; it pushed against her bladder like a pin piercing her belly. She wasn't going to make it today either. Every morning it was the same. After breakfast she would lock herself in the bathroom and push and push, trying to get rid of every last drop, contracting her abdominal muscles till her head ached and her eyes felt like they were going to pop out of their sockets. She would turn the tap full blast so that her father wouldn't hear the noises as she pushed and pushed, clenching her fists, to squeeze out the very last drop. She would sit there until her father pounded on the door and yelled so, missy, are we going to be late again today?

But it never did any good. By the time they reached the top of the first ski lift she would be so desperate that she would have to crouch down in the fresh snow and pretend to tighten her boots in order to take a pee inside her ski suit while all her classmates looked on, and Eric, the ski instructor, would say we're waiting for Alice, as usual. It's such a relief, she thought each time, as the lovely warmth trickled between her shivering legs. Or it would be, if only they weren't all there watching me.

Sooner or later they're going to notice.

Sooner or later I'm going to leave a yellow stain in the snow and they'll all make fun of me.

One of the parents went up to Eric and asked if the fog wasn't too thick to go all the way to the top that morning. Alice pricked up her ears hopefully, but Eric unfurled his perfect smile.

"It's only foggy down here," he said. "At the top the sun is blinding. Come on, let's go."

On the chairlift Alice was paired with Giuliana, the daughter of one of her father's colleagues. They didn't say a word the whole way up. Not that they particularly disliked each other, it was just that, at that moment, neither of them wanted to be there.

The sound of the wind sweeping the summit of the mountain was punctuated by the metallic rush of the steel cable from which Alice and Giuliana were hanging, their chins tucked into the collars of their jackets so as to warm themselves with their breath.

It's only the cold, you don't really need to go, Alice said to herself.

But the closer she got to the top, the more the pin in her belly pierced her flesh. Maybe she was seriously close to wetting herself. Then again, it might even be something bigger. No, it's just the cold, you don't really need to go again, Alice kept telling herself.

Alice suddenly regurgitated rancid milk. She swallowed it down with disgust.

She really needed to go; she was desperate.

Two more chairlifts before the shelter. I can't possibly hold it in for that long.

Giuliana lifted the safety bar and they both shifted their bottoms forward to get off. When her skis touched the ground Alice shoved off from her seat. You couldn't see more than two yards ahead of you, so much for blinding sun. It was like being wrapped in a sheet, all white, nothing but white, above, below, all around you. It was the exact opposite of darkness, but it frightened Alice in precisely the same way.

She slipped off to the side of the trail to look for a little pile of fresh snow to relieve herself in. Her stomach gurgled like a dishwasher. When she turned around, she couldn't see Giuliana anymore, which meant that Giuliana couldn't see her either. She herringboned a few yards up the hill, just as her father had made her do when he had gotten it into his head to teach her to ski. Up and down the bunny slope, thirty, forty times a day, sidestep up and snowplow down. Buying a ski pass for just one slope was a waste of money, and this way you trained your legs as well.

Alice unfastened her skis and took a few more steps, sinking halfway up her calves in the snow. Finally she could sit. She stopped holding her breath and relaxed her muscles. A pleasant electric shock spread through her whole body, finally settling in the tips of her toes.

Читать дальше