“Now!” Humphries shouted.

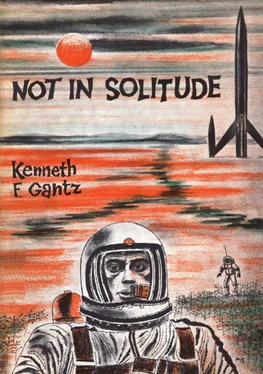

They stared at the photo plane table. The missile would move slowly enough. No need for hurry and supersonic speed here on Mars. It would pass circumspectly above the sands, its nose following its invisible pre-ordered path.

But when it did come to its detonation, there was only a wink of light on the plane table to announce it. Then as the reception image of the cloud spread deliberately, the burn area showed clearly on the glass.

“All clear!” the loudspeaker said. “All clear.”

Humphries’ face worked. “That’ll give them something to think about! He thrust suddenly at the port-cover switches, shoving at them.

The familiar explosion cloud hung in the Martian upper sky, spreading like surly contamination away from its funnel stem. Dane went close to the glassite port that faced the thing. He stood there for a long time, vague and wordless in mind, letting the feeling of ill-being vegetate, without fixation, without effort, gradually relaxing against it.

When the tension had ebbed, the troubled thought slowly emerged. Across the many millions of miles they had come, to be met with the old pattern of violence and to offer it up in return. The high skill of Earth expressed for a new world in the form of a nuclear bomb. Even against insensate plants the sign of limitless destruction.

IT BEGAN with darting filaments of lichen. They sprang out from the blasted end of the peninsula in radial tracery, fanning a net over the quarter-mile blotch of the burn. Dane strained his eyes at the scope. The net was filling in. In a minute it was a knob head on the stem of the peninsula. Filaments spurted ahead of the knob, spreading wider and inclining toward the spacecraft. In five minutes they had grown into mile-long streamers. Then, as suddenly as it had commenced, the phenomenon ceased.

“Dr. Dane to command post,” the speaker blared.

Dane hurried down the ladders. Before he swung off on 1-high deck he could hear argument, Wertz’s hoarse voice obscuring others.

The small command bay was crowded. Its door was open and men were overflowing into the passage. Major Noel sat at the command desk, idly snapping the key of the intercom. He nodded to Dane. “The gentleman of the press. We were discussing the lichens. Some of these other gentlemen are worried about the defense of the vehicle.” He was practically affable.

Wertz broke in again. “I’ve been trying to tell him the things are too dangerous to risk getting any closer to us. In the first place, it was a big mistake to use the fission bomb on them. Now we’ve got to get over there and burn off their growing ends.” He looked at his friend. “Even Cruzate here goes along with that. We all agree on that.”

Dane recognized the appeal for a recruit. He saw Forrest, the bacteriologist, and Wade, the zoologist, nod. The archaeologist Steffany kept his opinion to himself.

“It was a mistake to use fission on them,” Wertz repeated. “The radiation must have stimulated hell out of them. You’re not up against a growth like a plant. A better word for it would be a ‘formation.’ These things may resemble Earth lichens, but in one way they’re different as hell. They’re biochemical in the most literal sense of the word. They’re not plants. They’re biochemicals. With the accent on the chemical aspect of their existence. We saw the evidence right here in the Far Venture. What happened here proved it. They form themselves chemically, like crystals in a saturated solution. The fission radiation maybe stimulated new plants to form like hell.”

“What we’ve got to think about, at least what I have got to think about,” Noel said, “is the balance between any danger from the lichens and our resources to combat them. I’ve got to assume that if they keep on advancing I’ll have to keep them away from any contact with the Far Venture’s hull. Now when I think about that, I’ve got to think about how much fire fuel I have in hand to expend—maybe a total of eight or nine hours. I can’t defend a perimeter of three miles’ radius with that. Supposing we burn off the advance now, and then they come on again from a dozen other starts? I intend to hold a perimeter of about a hundred yards to a hundred and fifty in radius. I can hold that all the way around. We just wait until we can see the whites of their eyes, that’s all.”

Dane said, “There’s always the thought that actually we may completely misunderstand why the lichens are thrusting out at us. Just to hazard a wild guess, they might be a vehicle by which the Martians are approaching us. Maybe, for example, the Martians are parasitic upon them. Maybe they live within the plants, like bacteria in a blood stream.”

“Nothing wrong with your imagination,” Forrest spoke up. “But there really is something screwy about the whole life setup on this minus-two-dollar-an-acre ball of real estate. I don’t think we’ve given enough weight to it, except to be mighty puzzled by it. That’s the total absence of any sign or semblance of life on this planet and certainly in this area except these damn lichens. It just doesn’t add up. I’ll admit the lichen is a low form, but it’s a lot higher than many other forms of life. Bacteria, for instance. Why aren’t there any native bacteria observable here? With a big part of the surface covered with vegetation, there certainly should be a wide variety of unicellular organisms. What I’m getting at is how do these lichens have an apparent monopoly, as far as we know, on the life principle here?”

“Except for our mysteriously hidden Martians,” Dane reminded him.

“There is fossil evidence of the existence of blue-green algae and unicellular fungi on Earth two billion years ago” Wade said.

“Exactly,” Forrest answered the zoologist. “How do you doubt such forms existed on Mars? How about the algae-like components of the lichen plants here? Captured sometime surely from someplace by the fungus component. Did all the other one-celled organisms commit suicide? Why can’t we find any trace of evolutionary development? What I’m getting to is did the lichens come along later and somehow destroy every other form of life on the planet?”

“Oxygen,” Steffany asked, “how about the lack of oxygen? Wouldn’t that prevent any other form of life except something like the lichens with special apparatus for making their own?”

“There are anaerobic bacteria in the soil of Earth,” Forrest told him. “They exist in the absence of free oxygen. Why not here? No,” he went on, “I hardly can escape a conclusion that in some way all the forms of life that we might reasonably expect have been suppressed except the lichens.”

“How about Dane’s Martians?” Steffany put in.

“Obviously they have survived too,” Forrest said. “Maybe the lichens fit someway into their economy or plan of existence. That’s just it. How about the Martians? I wouldn’t want to say no to the idea that maybe they know all about these lichens and their peculiar growing actions. And maybe a lot more. It’s damned funny we can’t find any trace of bacterial life here. There’s nothing in the environment to forbid it. It suggests manipulation.”

Noel said, “Well, one thing we do know, we’ve got lichens if we haven’t got anything else. From what we know of them, we don’t want them in contact with the Far Venture. We can’t risk it. Any plan we make has got to be based on that. We start out with that.”

Wertz nodded. “That’s right for sure. We already know that they can attack timageel in their aggravated state. It could very well be that in their forming state—growing state if you want to call it that—they are especially acid-producing. Maybe the older formations that have been standing for a while are weaker. That could explain our walking through them in pressure suits. But it is precisely their growing peaks that the peninsula is addressing to us. Obviously if it reaches the spacecraft, it will impinge newly forming lichens against the timageel shell.”

Читать дальше