There were dozens of people around, but most of them seemed to avoid the Observer and the young captors. A few joined the group; all these seemed young, too, and there was much conversation which Bones could not, as usual, follow.

Half a dozen times the party turned into other passages, sometimes one way and sometimes the other. The turns were seldom exact right angles, and Bones’ sense of direction, which like that of the average human being depended entirely on memory if there were no sun or other long-range reference body, began to grow very shaky.

There were numerous doorways along the passages, some open and others blocked by doors.Bones was still trying to set up a reliable memory scheme for keeping count of these when the party turned into one of them.

The room they entered might have been called either a workshop or a laboratory. There were masses of wood, Newell tissue, and other structural materials lying around. Table tops bore tools of glass, stone, and even copper, as well as partly finished artifacts of obscure nature. There was another door on the far side.

They went through this. The next room was nearly bare, measuring some ten meters each way. The far quarter was separated from the rest by a set of bars extending from ceiling to floor. It was too dark to see just what the bars were made of and in any case Bones would not have noticed.

They made a very weak call for attention compared to the other Observer beyond them.

VI

Invaders, Indefinitely

Kahvi saw the people talking to her husband, but paid little attention. They had been expecting someone to come for the cargo, of course. The woman herself was busy with the routine of the raft-trimming and feeding oxygen and nitrogen plants, removing fruit and meat from other growths, feeding Danna and herself, making sure the child understood everything that was being done and letting her do much of it herself — educating her daughter; establishing the multitudinous hangups necessary for survival outside the cities. Some day the girl would have to do all this without help or supervision; her parents were already in their middle twenties.

The tent tissue had to be examined, as did the material making up the floats. Both were pseudolife products which sometimes continued to “live” in unexpected and inconvenient ways.

There was much less leisure for a Nomad than for a city-dweller. Danna, a normally intelligent five-year-old, was always asking questions. This evening she produced one which took her mother’s attention entirely away from the shore for some time. The child already knew much about pseudolife — the self-replicating chemical growths developed long before the change in Earth’s atmosphere to carry out various tasks or produce desired substances without human attention. She had seen many varieties, not only the Newell “plants” which produced structural material for the raft, and the photosynthetic producers of breathing oxygen, but even the metal-reducers which “lived” in the ocean and brought in copper, chromium, uranium, and other elements. She had grasped the general idea that pseudolife was human-designed and, originally, human-made and therefore “artificial” as opposed to “natural.”

She had, however, recently become aware of the expected sibling — she had been too young to be really aware of the others which had survived birth by only a few days or weeks — and become more realistically aware of her own origin. Now, naturally, she wanted to know why she herself was not artificial if her parents had “made” her.

Kahvi had no more luck with the ensuing discussion than parents had ever had before her, but it took all her attention for well over an hour. Danna had finally gone to sleep, dissatisfied and somewhat cranky, and the mother could once more turn her attention to the outside world and realize that Earrin had not yet come back.

She did not worry at first. Her husband might have had to do almost anything once the customers arrived — perhaps help carry the cargo to some other place, or go to fetch the payment. However, after some minutes of thought and several more of straining her eyes uselessly into the darkness, Kahvi checked the cartridge status by touch, assembled and donned her outdoor equipment, and slipped silently into the water. There was nothing to be afraid of in the sea except its trace of nitric acid, and she was as used to that as her ancestors had been to the far more deadly automobile.

There were no surviving real-life animal forms other than humanity from before the change; and in spite of the nitro-life’s tendency to easy mutation and consequent rapid evolution it had produced no animals much above microscopic size.None of these had developed the ability to parasitize human beings, though some were dangerous to air-cultures and other human necessities.

Kahvi surfaced at the land end of the raft with all her attention, therefore, directed toward the shore.

Nothing could be seen or heard but the ripple of waves on the beach, even with the tent tissue no longer in the way. She listened and looked for several minutes, and finally waded ashore. Dimly aided by vision, she found where they had stacked the cargo. It was still there.

Finally she called out her husband’s name. “ Earrin? Where are you?”

The answer was not in Fyn’s voice, and she started violently. “He’s not here, Kahvi Mikkonen, but is in no trouble.”

“Where is he? Why didn’t he tell me he was going? Who are you?”

“There was some danger, and we took him up to the hill.”

“What danger? The fire? We thought that was out, and — ”

“Not the fire. It is out.” The voice, originally some tens of meters away, was coming closer, though Kahvi could not yet see its owner. “I don’t want to frighten you, but your husband was being followed by an Invader.”

“What’s an Invader? And who are you? I don’t recognize your voice, but — ”

“But you’ve seen me before. I’m Jem Endrew. I met both of you when you were delivering copper a long time ago. Surely you’ve seen Invaders; you Nomads must meet them far oftener than those of us who live underground. They look like — well maybe you’ve never seen a book with a picture of a fish.”

There was just a suggestion that the voice had been going to continue, and Kahvi suspected that the Hiller had just stopped himself from adding, “Maybe you’ve never seen a book.”

“I have,” she replied. “They look a little like the metal-feeders we get your copper from.”

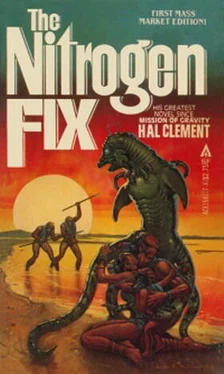

“I’ve never seen even a picture of those,” Endrew admitted. “Anyway, the Invaders have long bodies, anywhere from half or three quarters of a meter to two and a half or three. They’re fish-shaped, as I said.

A big one is maybe a third of a meter wide at the widest part, and not quite as thick. The tail goes sideways instead of up and down, and there are two long sort of flaps or fringes along the sides. They swim with a sort of up-and-down bending of the body and flaps and tail. There’s a big eye on each side in front of the flap, and a long ropy arm between the eye and the flap. The mouth goes across the top of the head — or the front, if it’s swimming — and opens sideways, and has little ropy arms around it. There are more of the ropy things in back — I’m not sure just how many. You’d think they were too thin, but the Invader can stand up on them and even run faster than a man. You really haven’t seen one?”

Kahvi was tempted to evade, but Nomad hangups overrode the urge.

“Oh, I’ve seen them, of course. We don’t call them — what was it — Invaders. Are they common here? Didn’t you used to call them Animals? I’ve only had a really good look at one of them.” The last statement was a strain; it was the truth, in a way, but certainly a truth likely to deceive.

Читать дальше