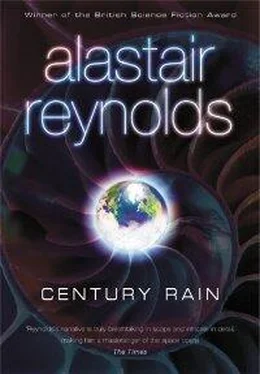

Century Rain

by Alastair Reynolds

The river flowing sluggishly under Pont de la Concorde was flat and grey, like worn-out linoleum. It was October and the authorities were having one of their periodic crackdowns on contraband. They had set up their customary lightning checkpoint at the far end of the bridge, backing traffic all the way across to the Right Bank.

“One thing I’ve never got straight,” Custine said. “Are we musicians supplementing our income with a little detective work on the side, or is it the other way round?”

Floyd glanced into the rear-view mirror. “Which way round would you like it to be?”

“I think I’d like it best if I had the kind of income that didn’t need supplementing.”

“We were doing all right until recently.”

“Until recently we were a trio. Before that, a quartet. Perhaps it’s just me, but I’m beginning to detect a trend.”

Floyd slipped the Mathis into gear and eased forward as the line advanced. “All we have to do is hold the fort together until she returns.”

“That isn’t going to happen,” Custine said. “She left for good when she got on that train. You keeping a seat free for her in the front of the car isn’t going to change things.”

“It’s her seat.”

“She’s gone.” Custine sighed. “That’s the trouble with recognising talent: sooner or later, someone else recognises it as well.” The big Frenchman rummaged in his jacket pocket. “Here. Show the nice man my papers.”

Floyd took the yellowing documents and placed them next to his own on the dashboard. When they reached the checkpoint, the guard flicked through Floyd’s papers and handed them back wordlessly. He thumbed through Custine’s, then leaned down until he had a good view into the back of the Mathis.

“On business, monsieur?”

“I wish,” Custine said quietly.

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“It means we were looking for work,” Floyd said amiably. “Unfortunately, we didn’t find any.”

“What kind of work?”

“Music,” Floyd said, gesturing around the car. “Hence the instruments.”

The guard jabbed the muzzle of his stamped-metal machine gun towards the soft fabric case of the double bass. “You could get a lot of cigarettes into that. Pull your vehicle over to the inspection area.”

Floyd slipped the old Mathis back into gear and crunched it forward, steering into a bay where the guards performed more detailed searches. To one side was a striped wooden cabin where the guards amused themselves with cards and cheap pornography. A low stone wall overlooked a narrow, pebbled quay. An empty chair stood by the wall, next to a large trestle table covered with a cloth.

“Say as little as possible,” Floyd said to Custine.

As the guard with the machine gun returned to his post, another from the inspection area knocked on the roof of the car. “Bring it out. Place it on the table.”

Floyd and Custine worked the case from the rear of the Mathis. It was cumbersome rather than heavy, and had already accumulated enough scuffs and scratches that a few more wouldn’t matter.

“You want me to open it?” Custine asked.

“Of course,” the second guard said. “And remove the instrument, please.”

Custine did as he was told, setting the double bass down gently. There was just enough room for it on the table next to the empty case. “There,” he said. “You’re welcome to examine the case if you think I have the ingenuity to hide something in it other than the instrument.”

“It’s not the case I’m concerned about,” the guard said. He motioned to one of his colleagues, who was sitting on a folding chair next to the striped cabin. The man put down his newspaper and picked up a wooden toolkit—an inspector of some kind, clearly. “I’ve seen these two before,” the guard continued. “They’re back and forth across the river like it’s going out of fashion. Makes you wonder, doesn’t it?”

The inspector narrowed his eyes at Custine. “I know this one,” he said. “Used to be a policeman, didn’t you? Some big cheese at Central Headquarters?”

“I felt a change of career would do me good.”

Floyd took a fresh toothpick from his shirt pocket, inserted into his mouth and bit down. The sharp end dug into his mouth, drawing blood.

“Quite a comedown, isn’t it, from high-profile police work to this?” the inspector persisted, setting his toolkit down.

“If you say so,” Custine replied.

The inspector picked up the double bass, shaking it with a look of deep concentration on his face before returning it to the table. “Nothing rattling around,” he said, reaching for his toolkit. “Still, they might have taped something to the inside. We’ll have to take this boy apart.”

Floyd saw Custine draw in a sharp breath and place his hands protectively on the double bass. “You can’t take it apart,” Custine said incredulously. “It’s an instrument. It doesn’t come apart.”

“In my experience,” the inspector said, “everything comes apart in the end.”

“Easy,” Floyd said. “Let them have it. It’s just a piece of wood.”

“Listen to your friend,” the guard suggested. “He talks good sense, especially for an American.”

“Take your hands from the instrument, please,” the inspector said.

Custine wasn’t going to do it. Floyd couldn’t blame him, not really. The double bass was the most expensive item Floyd owned, including the Mathis Emyquatre. Short of another investigation dropping into their laps, it was also about the only thing standing between them and penury.

“Let go,” Floyd mouthed. “Not worth it.”

The inspector and Custine began to struggle over the instrument. Drawn by the commotion, the guard with the machine gun who had stopped them originally left his post and began to saunter over to the action. The double bass was now off the table and the two men were yanking it backwards and forwards violently.

The guard with the gun slipped off its safety catch. The struggle intensified, Floyd fearing that the double bass was about to snap in two as the men wrestled with it. Then Custine’s opponent gained the upper hand and pulled the instrument out of Custine’s grasp. For a moment, the inspector froze, and then in a single fluid movement threw the double bass over the low wall on the other side of the examination table. Time dragged: it seemed an eternity before Floyd heard the awful splintering as the double bass hit the cobbled dock below. Custine sagged back into the chair next to the examination table.

Floyd spat out his toothpick, grinding it underfoot like a spent cigarette. He walked slowly to the wall and peered down to inspect the damage. It was ten, twelve metres to the cobbled quay. The bass’s neck was broken in two, the body smashed into myriad jagged pieces radiating away from the point of impact.

A scuffing of booted feet drew Floyd’s attention to his right. The second guard was on his way down to the quay, descending a stone staircase jutting out from the wall. Hearing a moaning sound to his left, Floyd glanced over to see Custine looking over the parapet. His eyes were wide and white as eggs, his pupils shrunken to shocked dots. Eventually his moaning formed into coherent sounds.

“No. No. No.”

“It’s done,” Floyd said. “And the sooner we get out of here, the better off we’ll be.”

“You destroyed history!” Custine shouted at the inspector. “That was Soudieux’s double bass! Django Reinhardt touched that wood!”

Floyd clamped a hand over his friend’s mouth. “He’s just a bit emotional,” he explained. “You’ll have to excuse him. He’s been under a lot of pressure lately, due to some personal difficulties. He apologises unreservedly for the way he has behaved. Don’t you, André?”

Читать дальше