Robert Silverberg - Homefaring

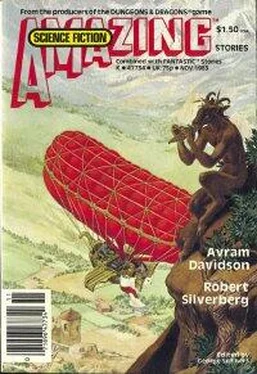

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Silverberg - Homefaring» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1983, Издательство: Dragon Publishing, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Homefaring

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dragon Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:1983

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Homefaring: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Homefaring»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Homefaring — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Homefaring», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“He is recovered now,” his host announced.

— What happened to me? McCulloch asked.

— Your people called you again. But you did not want to make your homefaring, and you resisted them. And when we understood that you wanted to remain, the god aided you, and you broke free of their pull.

— The god?

His host indicated the great octopus.

— There.

It did not seem at all improbable to McCulloch now. The infinite fullness of time brings about everything, he thought: even intelligent lobsters, even a divine octopus. He still could feel the mighty telepathic output of the vast creature, but though it had lost none of its power it no longer caused him discomfort; it was like the roaring thunder of some great waterfall, to which one becomes accustomed, and which, in time, one begins to love. The octopus sat motionless, its immense yellow eyes trained on McCulloch, its scarlet mantle rippling gently, its tentacles weaving in intricate patterns. McCulloch thought of an octopus he had once seen when he was diving in the West Indies: a small shy scuttling thing, hurrying to slither behind a gnarled coral head. He felt chastened and awed by this evidence of the magnifications wrought by the eons. A hundred million years? Half a billion? The numbers were without meaning. But that span of years had produced this creature. He sensed a serene intelligence of incomprehensible depth, benign, tranquil, all-penetrating: a god indeed. Yes. Truly a god. Why not?

The great cephalopod was partly sheltered by an overhanging wall of rock. Clustered about it were dozens of the scorpion-things, motionless, poised: plainly a guard force. Overhead swam a whole army of the big squids, doubtless guardians also, and for once the presence of those creatures did not trigger any emotion in the lobsters, as if they regarded squids in the service of the god as acceptable ones. The scene left McCulloch dazed with awe. He had never felt farther from home.

— The god would speak with you, said his host.

— What shall I say?

— Listen, first.

McCulloch’s lobster moved forward until it stood virtually beneath the octopus’s huge beak. From the octopus, then, came an outpouring of words that McCulloch did not immediately comprehend, but which, after a moment, he understood to be some kind of benediction that enfolded his soul like a warm blanket. And gradually he perceived that he was being spoken to.

“Can you tell us why you have come all this way, human McCulloch?”

“It was an error. They didn’t mean to send me so far— only a hundred years or less, that was all we were trying to cross. But it was our first attempt. We didn’t really know what we were doing. And I suppose I wound up halfway across time—a hundred million years, two hundred, maybe a billion—who knows?”

“It is a great distance. Do you feel no fear?”

“At the beginning I did. But not any longer. This world is alien to me, but not frightening.”

“Do you prefer it to your own?”

“I don’t understand,” McCulloch said.

“Your people summoned you. You refused to go. You appealed to us for aid, and we aided you in resisting your homecalling, because it was what you seemed to require from us.”

“I’m—not ready to go home yet,” he said. “There’s so much I haven’t seen yet, and that I want to see. I want to see everything. I’ll never have an opportunity like this again. Perhaps no one ever will. Besides, I have services to perform here. I’m the herald; I bring the Omen; I’m part of this pilgrimage. I think I ought to stay until the rites have been performed. I want to stay until then.”

“Those rites will not be performed,” said the octopus quietly.

“Not performed?”

“You are not the herald. You carry no Omen. The Time is not at hand.”

McCulloch did not know what to reply. Confusion swirled within him. No Omen? Not the Time?

— It is so, said the host. We were in error. The god has shown us that we came to our conclusion too quickly. The time of the Molting may be near, but it is not yet upon us. You have many of the outer signs of a herald, but there is no Omen upon you. You are merely a visitor. An accident.

McCulloch was assailed by a startlingly keen pang of disappointment. It was absurd; but for a time he had been the central figure in some apocalyptic ritual of immense significance, or at least had been thought to be, and all that suddenly was gone from him, and he felt strangely diminished, irrelevant, bereft of his bewildering grandeur. A visitor. An accident.

— In that case I feel great shame and sorrow, he said. To have caused so much trouble for you. To have sent you off on this pointless pilgrimage.

— No blame attaches to you, said the host. We acted of our free choice, after considering the evidence.

“Nor was the pilgrimage pointless,” the octopus declared. “There are no pointless pilgrimages. And this one will continue.”

“But if there’s no Omen—if this is not the Time—”

“There are other needs to consider,” replied the octopus, “and other observances to carry out. We must visit the dry place ourselves, from time to time, so that we may prepare ourselves for the world that is to succeed ours, for it will be very different from ours. It is time now for such a visit, and well past time. And also we must bring you to the dry place, for only there can we properly make you one of us.”

“I don’t understand,” said McCulloch.

“You have asked to stay among us; and if you stay, you must become one of us, for your sake, and for ours. And that can best be done at the dry place. It is not necessary that you understand that now, human McCulloch.”

— Make no further reply, said McCulloch’s host. The god has spoken. We must proceed.

Shortly the lobsters resumed their march, chanting as before, though in a more subdued way, and, so it seemed to McCulloch, singing a different melody. From the context of his conversation with it, McCulloch had supposed that the octopus now would accompany them, which puzzled him, for the huge unwieldy creature did not seem capable of any extensive journey. That proved to be the case: the octopus did not go along, though the vast booming resonances of its mental output followed the procession for what must have been hundreds of miles.

Once more the line was a single one, with McCulloch’s host at the end of the file. A short while after departure it said:

— I am glad, friend human McCulloch, that you chose to continue with us. I would be sorry to lose you now.

— Do you mean that? Isn’t it an inconvenience for you, to carry me around inside your mind?

— I have grown quite accustomed to it. You are part of me, friend human McCulloch. We are part of one another. At the place of the dry land we will celebrate our sharing of this body.

— I was lucky, said McCulloch, to have landed like this in a mind that would make me welcome.

— Any of us would have made you welcome, responded the host.

McCulloch pondered that. Was it merely a courteous turn of phrase, or did the lobster mean him to take the answer literally? Most likely the latter: the host’s words seemed always to have only a single level of meaning, a straightforwardly literal one. So any of the lobsters would have taken him in uncomplainingly? Perhaps so. They appeared to be virtually interchangeable beings, without distinctive individual personalities, without names, even. The host had remained silent when McCulloch had asked him its name, and had not seemed to understand what kind of a label McCulloch’s own name was. So powerful was their sense of community, then, that they must have little sense of private identity. He had never cared much for that sort of hive-mentality, where he had observed it in human society. But here it seemed not only appropriate but admirable.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Homefaring»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Homefaring» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Homefaring» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.