‘Meng-fu crater itself is massive, it dominates the horizon as you approach, and when you go down into it, well – it’s just one huge black pit; you can’t see anything inside it. It feels like you’re just falling down into nothingness. When you’re deep down inside the crater, and you get used to the darkness, you can see the mine and the refinery lights from some way off, and then as you get closer you can see the landing pad itself – it was floodlit then, but of course it won’t be for us.’

Clare nodded, and took a drink of her coffee, but Matt sensed he hadn’t told her anything she didn’t know already.

‘So, why do you want to go back?’ she asked suddenly.

Matt was surprised by the directness of her question, and his mouth fell open slightly.

‘I – represent the relatives class action group, and—’

‘I know what you’re there to do,’ she interrupted, ‘but the relatives would never have proposed you as their representative if you hadn’t wanted to go back.’

Matt wondered if he wanted to tell her. The directness of this serious young woman was disconcerting.

What the hell. They had to spent months cooped up together anyway.

‘Well, the accident left me feeling – like I’d escaped, and they hadn’t. I wasn’t any better than any of them, it could have been me in the mine. Going back makes me feel like I’m somehow making – amends for things.’

Matt paused. It had been a long time since anyone had asked him how he felt about anything. His throat had gone dry, and the last words had been difficult to get out. He took another drink of his coffee.

Clare stared back at him for several seconds before replying, but her gaze had softened.

‘So. You feel guilty for surviving. It’s not unusual. But there must be other ways of coping than by going back. Haven’t you been offered any counselling?’

Matt looked down, and he hesitated, wondering if he should tell her.

‘Yes – I had several sessions in the early days after the accident,’ he said at last, ‘but it didn’t really help, and I stropped going after a while. I felt such a fake – I was one of the survivors, after all.’

‘It doesn’t mean you don’t deserve a bit of help.’

‘Maybe. But none of the counselling seemed to work. I guess that’s why I got involved with the relatives, and the class action – I felt like I was helping people who really needed it.’

Clare waited, listening.

‘I just need to know what happened. I keep seeing it – the accident – imagining what it was like for them. It’s worse than not knowing. I’ve got to go back and see it with my own eyes. I’ve got to know how they died.’

Helligan stood at the front of the room as they finished their break, flanked by a thin, sandy-haired man in civilian clothes. Matt recognised him from earlier briefings as Rawlings, the mission planner.

Rawlings was one of the civilian specialists retained by the Corps for their expertise in crucial areas. He had a hurried manner that gave the impression of him never having enough time, and the pale complexion of someone who spent too much of his time away from the Sun, in darkened control rooms in the bowels of FSAA facilities. He seemed nervous and ill at ease as Helligan introduced him to the team, and as Helligan went to sit at the back of the room, Rawlings dimmed the lights at once, as if he felt safer in the familiar darkness.

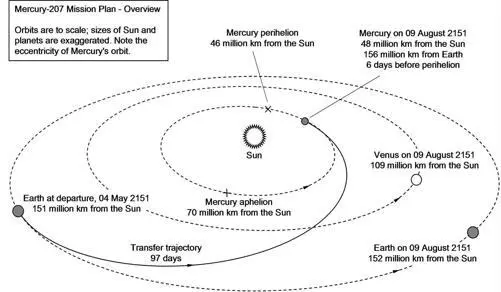

A view of the Inner Solar System appeared on the viewscreen wall behind Rawlings, silhouetting his head and shoulders.

At the centre of the display, a tiny Sun burned, and the planets circled round it like glittering marbles in space, following the coloured ellipses of their orbits as they moved round in accelerated time.

The display zoomed in on the three innermost planets. The blue globe of the Earth moved slowly at the edge of the screen, Venus a little faster, following the yellow circle of its closer orbit, and finally Mercury, pursuing its highly eccentric orbit close to the Sun.

‘This is the situation of the planets right now,’ the silhouette of Rawlings said, freezing the display. ‘The launch window we’re recommending is here—’ he fast forwarded the display a few months ‘—in the early hours of May fourth. Transfer orbit insertion at zero six thirty UTC will put you onto a minimum-energy trajectory to Mercury, with a journey time of just over ninety-seven days.’

The display moved forward again, and a thin green line sprouted from Earth and curved inward, converging on Mercury. The mission planner stopped the display as the green line touched the innermost planet.

‘Your rendezvous with Mercury is on August ninth, six days before Mercury’s closest approach to the Sun. The orbit insertion manoeuvre takes you over the North Pole, and into a standard polar orbit.’

Rawlings zoomed in closer on the display, and the tiny dot of Mercury expanded until it became a grey globe. A graphic of a space tug appeared at the end of the green line, moving against the background of the stars. The mission team watched as the tug fired its engine, slowing down and moving into a circular orbit around Mercury.

Clare leaned forward. The tiny aircraft-shape attached to the front of the tug occupied her full attention.

‘Just a moment,’ she said.

Rawlings halted the animation.

‘What kind of ship are we going down to the surface in?’ She pointed at the screen.

‘You’re going to be flying one of the Martian spaceplanes – most likely a modified Olympus two-forty,’ Rawlings said quickly, glancing towards the back of the room. ‘We had one back from Mars last month that needed a major overhaul. We’ve bumped it up the priority list, and it’ll be refitted for the mission.’

‘You’ve got to be kidding.’ Clare shook her head in disbelief. ‘Why are we taking a spaceplane down to Mercury? Why can’t we use one of the crew shuttles?’

‘Because we don’t know what state the landing pad is in after the refinery explosion,’ Helligan’s drawl cut in from behind her. ‘If the pad’s been put out of action by the explosion, a shuttlecraft won’t be able to land.’

Clare started to speak, but Helligan waved a hand dismissively, and continued: ‘Look, shuttlecraft are designed for landing on flat, concrete pads; they’re not able to land on crater floors. And they don’t have the radiation shielding for an extended stay on the surface. Those spaceplanes are built to operate off dirt strips on Mars – they can take hard landings on rough terrain, and they’ve got plenty of shielding. It’s a safer option.’

Clare subsided for the moment. Helligan had a point. If they had to land on the uneven terrain of a crater floor, she would rather be in the spaceplane. Still, it was a big, heavy craft to haul all the way to Mercury.

‘What about living space when we’re on the surface? We might be there for some time,’ she asked.

‘Inflatable Mars habitat modules, carried in the spaceplane’s cargo bay,’ Rawlings answered. ‘The spaceplane can supply all the power and air you need to run them while you’re there. The habitats have adequate radiation shielding for your stay, but you’ll have to retreat into the spaceplane if there’s a major solar event. In the most extreme cases, you may need to take shelter in the mine itself.’

Clare nodded as she made a note in her pad. They seemed to have thought it all out.

Rawlings was looking at her, as if waiting to see if she had more objections. She nodded for him to continue.

Читать дальше