Begin what?

The girl touched him and he roused, uncertain for a wild moment where he was. There was a burnt, smoky odor in the air.

“Do you want to eat?” she said. She put a plate of brown chunks before him. Then she sat too, a little way off, as though uncertain how he might respond.

“It’s meat,” he said.

“Sure.” She said it encouragingly. “It’s okay.”

“I can’t.”

“Are you sick?”

“We don’t eat meat.” A broken, blanched bone protruded from one brown piece.

“So eat grass,” she said, and rose to go. He saw he had rejected a kindness, a human kindness, and that she was the only one here capable of offering him that — and of talking to him, too.

“No, don’t go, wait. Thank you.” He picked up a piece of the meat, thinking of her tearing it bloody from its skin. “It’s just — I never did.” The smell of it — burned, dark, various — was heady, heady as sin. He bit, expecting nausea. His mouth suddenly filled with liquid; he was eating flesh. He wondered how much he needed in order to make a meal. The taste seemed to start some ancient memory: a race memory, he wondered, or just some forgotten childhood before the Mountain?

“Good,” he said, chewing carefully, feeling flashes of guilty horror. He wouldn’t keep it down, he was certain; he would vomit. But his stomach said not so.

“Do you think,” he said, pushing away his plate, “that they’ll talk to me?”

“No. Maybe Painter. Not the others.”

“Painter?”

“The one you talked to.”

“Is he, well, the leader, more or less?”

She smiled as though at some interior knowledge to which Meric’s remark was so inadequate as to be funny.

“How do you come to be here?” he asked.

“His.”

“Do you mean like a servant?”

She only sat, plucking at the grass between her boots. She had lost the habit of explanation. She was grateful it was gone, because this was unexplainable. The question meant nothing; like a leo, she ignored it. She rose again to go.

“Wait,” he said. “They won’t mind if I stay?”

“If you don’t do anything.”

“Tell me. That one up on the hill. What’s his function?”

“His what?”

“I mean why is he there, and not here? Is he a guard?”

She took a step toward him, suddenly grave. “He’s Painter’s son,” she said. “His eldest. Painter put him out.”

“Put him out?”

“He doesn’t understand yet. He keeps trying to come back.” She looked off into the darkness, as though looking into the blank face of an unresolvable sadness. Meric saw that she couldn’t be yet twenty.

“But why?” he said.

She retreated from him. “You stay there,” she said, “if you want. Don’t make sudden moves or jump around. Help when you can, they won’t mind. Don’t try to understand them.”

Just before dawn they began to rise. Meric, stiff and alert after light, hallucinatory sleep, watched them appear in the blue, bird-loud morning. They were naked. They gathered silently in the court of the camp, large and indistinct, the children around them. They all looked east, waiting.

Painter came from his tent then. As though signaled by this, they all began to move out of the camp, in what appeared to be a kind of precedence. The girl, naked too, was last but for Painter. Meric’s heart was full; his eyes devoured what they saw. He felt like a man suddenly let out of a small, dark place to see the wide extent of the world.

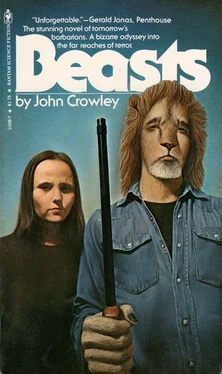

Outside the camp, the ground fell away east down to a rushy, marshy stream. They went down to the stream, children hurrying ahead. Meric rose, cramped, wondering if he could follow. He did, loitering at what he hoped was a respectful distance. As they walked down, he studied the strangeness of their bodies. If they were conscious of his presence, or of their own nakedness, they didn’t show it; in fact they didn’t seem naked as naked humans do, skinned and raw and defenseless, with unbound flesh quivering as they walked. They seemed clothed in flesh as in armor. A kind of hair, a blond down, as thick as loincloths between the females’ legs, made them seem not so much hairy as cloudy. Walking made their muscles move visibly beneath the cloud of hair, their massive thighs and broad backs changing shape subtly as they took deliberate steps down to the water. In the east, a fan of white rays shot up suddenly behind downslanting bars of scarlet cirrus, and upward into the blue darkness overhead. They raised their faces to it.

Meric knew that they considered the sun a god and a personal father. Yet what he observed had none of the qualities of a ritual of worship. They waded knee-deep into the water and washed, not ritual ablutions but careful cleansing. Women washed children and males, and older children washed younger ones, inspecting, scrubbing, bringing up handfuls of water to rinse one another. One female calmly scrubbed the girl, who shrank away grimacing from the force of it; her body was red with cold. Painter stood bent over, hands on his knees, while the girl and another laved his back and head; he shook his head to remove the water and wiped his face. A male child splashing near him attempted to catch him around the neck and Painter threw him roughly aside, so that the child went under water; Painter caught him up and dunked him again, rubbing his spluttering face fiercely. Impossible to tell if this was play or anger. They shouted out now and again, at each other’s ministrations or at the coldness of the water, or perhaps only for shouting; for a spark of sun flamed on the horizon, and then the sun lifted itself up, and the cries increased.

It was laughter. The sun smiled on them, turning the water running from their golden bodies to molten silver, and they laughed in his face, a stupendous fierce orison of laughter.

Meric, estranged on the bank, felt dirty and evanescent, and yet privileged. He had wondered about the girl, how she could choose to be one of them when she so obviously couldn’t be; how she could deny so much of her own nature in order to live as they did. He saw now that she had done no such thing. She had only acceded to their presence, lived as nearly as she could at their direction and convenience, like a dog trying to please a beloved, contrary, willful, godlike man, because whatever selfdenial that took, whatever inconvenience, there was nothing else worth doing. Inconvenience and estrangement from her own kind were nothing compared to the privilege of hearing, of sharing, that laughter as elemental as the blackbird’s song or the taste of flesh.

When they came back into camp they remained naked in the warming sunlight for a time, drying. Only the girl dressed, and then began to make up the fire. If she looked at Meric she didn’t seem to see him; she shared in their indifference.

When he moved, though, there wasn’t one of them who didn’t notice it. When he went to his pack and got bread and dried fruit, all their eyes caught him. When he assembled his recorder, they followed his movements. He did it all slowly and openly, looking only at the machine, to make them feel it had nothing to do with them.

Painter had gone into his tent, and when Meric was satisfied that his recorder was in working order, he stood carefully, feeling their eyes on him, and went to the tent door. He squatted there, peering into the obscurity within, unable to see anything. He thought perhaps the leo would sense his presence and come to the door, if only to chase him off. But, no notice was taken of him. He felt the leo’s disregard of him, so total as to be palpable.

He was not present, not even to himself; he was a prying eye only, a wavering, shuddering needle of being without a north.

“Painter,” he said at last. “I want to talk to you.” He had considered politer locutions; they seemed insulting, even supposing the leo would understand them as politeness. He waited in the silence. He felt the eyes of the pride on him.

Читать дальше