It was on nights like this that Meric and she, wrapped in the delicate tissue of the Mountain’s life-sounds, made their still love. She opened the robe of Blue and touched her nakedness delicately, following carefully to the end the long shivers that her fingers started. Meric… Like grace, the lovely feelings were suddenly withdrawn from her. Meric. Where was he? Out there, in the limitless darkness, looking at those creatures. What would they do? They seemed to her dangerous, unpredictable, hostile. She wished — so hard it was a prayer — that Meric were here in the shelter of the Mountain.

She surrendered to the anxious tightening of her body, rolling on her side and drawing up her knees. Her eyes were wide open, and she listened to the sounds more intently now, searching them. And — in answer to her prayer, she was certain of it — she sorted from the ambience footsteps coming her way, the sound altering in a familiar way as Meric turned corners toward her. It was his tread. She turned over and could see him, as pale as a wax candle in the darkness of the house. He put down his bundles.

“Meric.”

“Yes. Hello.”

Why didn’t he come to her? She rose, pulling the robe around her, and tiptoed across the cold floor to hug him, welcome him back to safety.

His smell when she took hold of him was so rank she drew back. “Jesus,” she said. “What…”

He turned up the tapers. His face was as smooth and delicate as ever, but its folds and lines seemed deeper, as though filled with blown black dust. His eyes were huge. He sat carefully, looking around himself as though he had never seen this place before.

“Well,” she said, uncertain. “Well, you’re back.”

“Yes.”

“Are you hungry? You must be hungry. I didn’t think. Wait, wait.” She touched him, so that he would stay, and went quickly to make tea, cut bread.

“You’re all right,” she said.

“Yes. All right.”

“Do you want to wash?” she asked when she brought the food. He didn’t answer; he was sorting through the bag, taking out discs and reading the labels. He ignored the tray she put before him and went to the editing table he kept in the house for his work. Bree sat by the tray, confused and somehow afraid. What had happened to him out there to make him strange like this? What had they done to him, what horrors had they shown him? He chose a disc and inserted it; then, with quick certainty, set up the machine and started it.

“Turn down the light,” he said. “I’ll show you.”

She did, turning away from the screen, which was brightening to life, not certain she wanted to see.

A girl’s voice came from the speakers: “…and wherever they go, I’ll go. The rest doesn’t matter to me anymore. I’m lucky…”

Bree looked at the screen. There was a young woman with short, dark hair. She sat on the ground with her knees drawn up, and plucked at the grass between her boots. Now and again she looked up at the camera with a kind of feral shy daring, and looked away again. “My god,” said Bree. “Is she human?”

“No,” the girl said in response to an unheard question. “I don’t care about people. I guess I never liked them very much.” She lowered her eyes. “The leos are better than people.”

“How,” Bree asked, “did she get there? Did they kidnap her?”

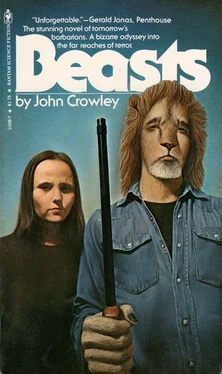

“No,” Meric said. “Wait.” He slid a lever and the girl began to jerk rapidly like a puppet; then she leapt up and fled away. There was a flicker of nothing, and then Meric slowed the speed to normal again. There was a tent, and standing before it was a leo. Bree drew her robe tighter around her, as though the creature looked at her. His gaze was steady and changeless; she couldn’t tell what emotion it expressed: patience? rage? indifference? So alien, so unreadable. She could see the muscles of his heavy, squat legs beneath the ordinary jeans, and of his wide shoulders; at first she thought he wore gloves, but no, those were his own blunt hands. He held a rifle, casually, as though it were a wrench.

“That’s him,” Meric said.

“Him?”

“He’s called Painter. Anyway, she calls him Painter. Not the others. They don’t use names, I don’t think.”

“Did you talk to him? Can he talk?”

“Yes.”

“What did he say?”

The leo began to move away from the tent door, but Meric reversed the disc and put him back again. He stood at the tent door and regarded the humans from his electronic limbo.

What had he said?

When Meric had gone down to where the leo stood broad and poised in the twilight, the leo hadn’t spoken at all. Meric, in tones as pacific and self-effacing as he could make them, tried to explain about the Mountain, how this land was theirs.

“Yours,” the leo said. “That’s all right.” As though forgiving him for the error of ownership.

“We wanted to see,” Meric began, and then stopped. He felt himself in the grip of an intelligence so fierce and subtle that it made an apprehensive hollow in his chest. “I mean ask — see — what it was you’d come for. I came out. Alone. Unarmed.”

The girl he had seen, and the females, had retreated into the shelter of the roofless farmhouse, not as though afraid but as though he were a phenomenon that didn’t interest them and could be left for this male to dismiss. Someone within the walls was blowing a fire to life; spark-lit smoke rose over the walls. The young ones still played their silent games, but farther off. They looked at him now and again; stared; stopped playing.

“Well, you’ve seen,” the leo said. “Now you can go.”

Meric lowered his eyes, not wanting to be arrogant, and also not quite able to face the leo’s regard. “They wonder about you,” he said. “In the Mountain. They don’t know you, what you are, how you live.”

“Leos,” said the leo. “That’s how we live.”

“I thought,” Meric went on — it was exhausting to stand face to face like this, at a boundary, an intruder, and yet try to be intimate, carefully friendly, tentative — I thought if I could just — talk with you, take some pictures, make recordings — just the way you live — I could take them back and show the others. So they could —” He wanted to say “make a decision about you,” but that would sound offensive, and he realized at that moment that it was an impossibility as well: the creature before him would allow no decisions to be made about him. “So they could all see, you know,” he finished lamely.

“See what?”

“Would you mind,” Meric said, “if I sat down?” He took two careful steps forward, his heart beating hard because he didn’t know just where he might step over some inviolable boundary and be attacked, and sat down. That was better. It gave the leo the superior position. Meric had made himself absolutely vulnerable, could be no threat here on the ground; yet he was now truly within their boundaries. He essayed a smile. “Your hunting went well,” he said.

It would be a long time before Meric learned that such conversational pioys were meaningless to leos. Among men they were designed to begin a chat, to put at ease, to bridge a gap; were like a touch or a smile. The leo answered nothing. He hadn’t been asked a question. The man had made a statement. The leo supposed it to be true. He didn’t wonder why the man had chosen to make it. He decided to forget him briefly, and turned away into the enclosure, leaving Meric sitting on the ground.

Night gathered around him. He made up his mind to remain where he was as long as he could, to grow into the ground, become ignorable. He took a yoga position he knew he could hold for hours without discomfort. He could even sleep. If they slept, and let him sleep here, in the morning he might have become a fixture, and could begin.

Читать дальше