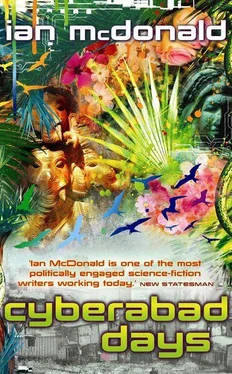

Ian McDonald - Cyberabad Days

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian McDonald - Cyberabad Days» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Gollancz, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Cyberabad Days

- Автор:

- Издательство:Gollancz

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-591-02699-0

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Cyberabad Days: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Cyberabad Days»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

); a new, muscular superpower in an age of artificial intelligences, climate-change induced drought, strange new genders, and genetically improved children.

Cyberabad Days — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Cyberabad Days», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘My little quiz?’ Jasbir asked.

‘Devashri Didi gave me the answers you were expecting. She’d told me it was a standard ploy, personality quizzes and psychic tests.’

‘And the Sanskrit?’

‘Can’t speak a word.’

Jasbir laughed honestly.

‘The personal spiritual journey?’

‘I’m a strictly material girl. Devashri Didi said…’

‘…I’d be impressed if I thought you had a deep spiritual dimension. I’m not a history buff either. And An Eligible Boy ?’

‘That unreadable tripe?’

‘Me neither.’

‘Is there anything true about either of us?’

‘One thing,’ Jasbir said. ‘I can tango.’

Her surprise, breaking into a delighted smile, was also true. Then she folded it away.

‘Was there ever any chance?’ Jasbir asked.

‘Why did you have to ask that? We could have just admitted that we were both playing games and shaken hands and laughed and left it at that. Jasbir, would it help if I told you that I wasn’t even looking? I was trying the system out. It’s different for suitable girls. I’ve got a plan.’

‘Oh,’ said Jasbir.

‘You did ask and we agreed, right at the start tonight, no more pretence.’ She turned her coffee cup so that the handle faced right and laid her spoon neatly in the saucer. ‘I have to go now.’ She snapped her bag shut and stood up. Don’t walk away , Jasbir said in his silent Master of Grooming, Grace and Gentlemanliness voice. She walked away.

‘And Jasbir.’

‘What?’

‘You’re a lovely man, but this was not a date.’

A monkey takes a liberty too far, plucking at Jasbir’s shin. Jasbir’s kick connects and sends it shrieking and cursing across the platform. Sorry, monkey. It wasn’t you . Booms rattle up the subway tube; gusting hot air and the smell of electricity herald the arrival of the last metro. As the lights swing around the curve in the tunnel, Jasbir imagines how it would be to step out and drop in front of it. The game would be over. Deependra has it easy. Indefinite sick leave, civil service counselling and pharma. But for Jasbir there is no end to it and he is so so tired of playing. Then the train slams past him in a shout of blue and silver and yellow light, slams him back into himself. He sees his face reflected in the glass, his teeth still divinely white. Jasbir shakes his head and smiles and instead steps through the opening door.

It is as he suspected. The last phatphat has gone home for the night from the rank at Barwala metro station. It’s four kays along the pitted, flaking roads to Acacia Bungalow Colony behind its gates and walls. Under an hour’s walk. Why not? The night is warm, he’s nothing better to do and he might yet pull a passing cab. Jasbir steps out. After half an hour a last, patrolling phatphat passes on the other side of the road. It flashes its light and pulls around to come in beside him. Jasbir waves it on. He is enjoying the night and the melancholy. There are stars up there, beyond the golden airglow of great Delhi.

Light spills through the French windows from the verandah into the dark living room. Sujay is at work still. In four kilometres Jasbir has generated a sweat. He ducks into the shower, closes his eyes in bliss as the jets of water hit him. Let it run let it run let it run. He doesn’t care how much he wastes, how much it costs, how badly the villagers need it for their crops. Wash the old tired dirt from me.

A scratch at the door. Does Jasbir hear the mumble of a voice? He shuts off the shower.

‘Sujay?’

‘I’ve, ah, left you tea.’

‘Oh, thank you.’

There’s silence but Jasbir knows Sujay hasn’t gone. ‘Ahm, just to say that I have always… I will… always. Always…’ Jasbir holds his breath, water running down his body and dripping on to the shower tray. ‘I’ll always be here for you.’

Jasbir wraps a towel around his waist, opens the bathroom door and lifts the tea.

Presently Latin music thunders out from the brightly lit windows of Number 27 Acacia Bungalows. Lights go on up and down the close. Mrs Prasad beats her shoe on the wall and begins to wail. The tango begins.

The Little Goddess

I remember the night I became a goddess.

The men collected me from the hotel at sunset. I was light-headed with hunger, for the child-assessors said I must not eat on the day of the test. I had been up since dawn, the washing and dressing and making-up was a long and tiring business. My parents bathed my feet in the bidet. We had never seen such a thing before and that seemed the natural use for it. None of us had ever stayed in a hotel. We thought it most grand, though I see now that it was a budget tourist chain. I remember the smell of onions cooking in ghee as I came down in the elevator. It smelled like the best food in the world.

I know the men must have been priests but I cannot remember if they wore formal dress. My mother cried in the lobby; my father’s mouth was pulled in and he held his eyes wide, in that way that grown-ups do when they want to cry but cannot let tears be seen. There were two other girls for the test staying in the same hotel. I did not know them; they were from other villages where the devi could live. Their parents wept unashamedly. I could not understand it; their daughters might be goddesses.

On the street, rickshaw drivers and pedestrians hooted and waved at us with our red robes and third eyes on our foreheads. The devi, the devi, look! Best of all fortune! The other girls held on tight to the men’s hands. I lifted my skirts and stepped into the car with the darkened windows.

They took us to the Hanumandhoka. Police and machines kept the people out of Durbar Square. I remember staring long at the machines, with their legs like steel chickens and naked blades in their hands. The President’s Own fighting machines. Then I saw the temple and its great roofs sweeping up and up and up into the red sunset and I thought for one instant its upturned eaves were bleeding.

The room was long and dim and stuffily warm. Low evening light shone in dusty rays through cracks and slits in the carved wood; so bright it almost burned. Outside, you could hear the traffic and the bustle of tourists. The walls seemed thin but at the same time kilometres thick. Durbar Square was a world away. The room smelled of brassy metal. I did not recognise it then but I know it now, it is the smell of blood. Beneath the blood was another smell, of time piled thick as dust. One of the two women who would be my guardians if I passed the test told me the temple was five hundred years old. She was a short, round woman with a face that always seemed to be smiling but when you looked closely you saw it was not. She made us sit on the floor on red cushions while the men brought the rest of the girls. Some of them were crying already. When there were ten of us the two women left and the door was closed. We sat for a long time in the heat of the long room. Some of the girls fidgeted and chattered but I gave all my attention to the wall carvings and soon I was lost. It has always been easy for me to lose myself; in Shakya I could disappear for hours in the movement of clouds across the mountain, in the ripple of the grey river far below and the flap of the prayer banner in the wind. My parents saw it as a sign of my inborn divinity, one of thirty-two that mark girls in whom the goddess could dwell.

In the failing light I read the story of Jayaprakash Malla playing dice with the devi Taleju Bhawani who came to him in the shape of a red snake and left with the vow that she would only return to the rulers of Kathmandu as a virgin girl of low caste, to spite their haughtiness. I could not read its end in the darkness, but I did not need to. I was its end, or one of the other nine girls in the god-house of the devi.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Cyberabad Days»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Cyberabad Days» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Cyberabad Days» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.