The’ Loon studied the quillion and his own spring-knife, shrugged, and made the blade disappear into his handle. “Take your farkin picture, then, brasser. May the cat eat you and the shayten eat the cat.” He stepped away with ill grace.

“Thank you,” she said sweetly, and tucked the quillion back into its cache. Raising her imager, she hoped her hand would not shake too much. Half the advantage was projecting a mien of confidence. She wondered if she could have followed through on her implied threat. It was one thing to practice on dummies in Mother’s gymnasium; another thing entirely to face a living man.

The sun was low, illuminating the west side of the Cones. One of the holes in the side of the largest cone—the one they called Momad—received the light directly, revealing a tangled mess of broken decking. Supposedly, there was a chamber deep inside called the gáván gofthayin , where the ruler was buried. A bird flew toward the hole, probably to a nest inside, and impulsively Méarana captured that image.

The backdrop was impressive, too. The irregular cluster of hills behind the Cones was also deeply shadowed by the setting sun, and in the dim light they looked almost as if they, too, were cones arrayed in serried ranks.

That was plain silly. An entire mountain range of these things?

Behind her, Méarana heard the warning hoot from the air bus platform and the hum as the magnets on the rail kicked in to receive the incoming bus. So she stuffed package and comm in the pockets of her jacket, pulled her chabb tight against the shrogo wind and hurried to the departure ramp. Glancing back, she saw the’ Loon genuflect on one knee toward the Cones and touch his breast, lips, forehead, and shoulders with the fingers of his right hand.

Despite his knife and his menace and his banty-cock threat, her heart went out to him. Did not everyone deserve something sacred?

She had agreed to meet Donovan at the Café Gwiyom, and there Méarana discovered the scarred man already worrying two fingers of uiscebaugh. He was not drunk, but he was immersed in that morose frame of mind that soured his every word. Drunks at least were sometimes cheerful. Méarana hesitated at the threshold, for she had not seen him in such a state since leaving Jehovah.

She considered the possibility of going on without him. If she left him here, he would barely notice. He would sink into the Terran demimonde and into the prison of his past. But she had invested too much effort in the finding of him and could not bring herself to forgo the return on that investment. And if the Fudir had the prison of his past, did she not have the prison of her future? Growing up, she had learned the art of patience.

She had forgotten that the scarred man was a man of parts, and one part, keeping vigil through his right eye, saw her standing irresolute in the entry, and his arm waved her inside. So she gathered herself, her thoughts, and her excitement and hurried to the table.

It was a bright and open café, unlike the Bar on Jehovah: spacious where the Bar was dense, well-lit where the Bar was dark, its clientele careless where the Bar’s were more carefree. And yet the scarred man had contrived, like a tea ball steeping in hot water, to lend the facility some of the hue of his former estate.

As always, the table he had chosen nestled near the rear wall of the café with himself facing the room. Never sit with you back to the room , he had told her once. You have to see them coming . Fine advice, she had thought, from one already occupying the recommended seat. And to “see them coming” didn’t you have to lift your gaze from the fascination of the whiskey?

She took the siege perilous opposite him, with her back defiantly to the room, and placed the package on the table. The scarred man did not lift his head, but she thought those restless eyes of his sought it out and found the name to which it had been addressed, for the grip of his hand on the tumbler tightened and his knuckles grew white.

“It’s been waiting for her at Côndefer Park for two years metric,” she told him. “It was all I could do on the air bus to keep from ripping it open; but… You know what it means? Whoever left the package would have notified her through the Circuit and… If we simply wait at the Park, eventually she will come to pick it up, or send a message to forward it…”

“We’d wait as long as the Cones, and the birds of the air would make their nests in our beards. And,” this he said more forcefully, “if she hasn’t come for it in two years, you will, sooner or later, have to face what that really means.”

“It could be that she changed her itinerary and the message went to the wrong world; or it reached her hotel after she had left and the hotel didn’t know where to forward it. Or she went to a world outside the Circuit. Or…”

The scarred man looked up from the table. “ Or she’s dead! Whatever she had been looking for, she found it. Or it found her.”

Méarana stuck her chin out. “Or the package meant less to her than it did to its sender.”

“You think she left it behind on purpose?”

The harper hesitated, then looked away. “She leaves a great many things behind.”

They fell silent, each with their own thoughts, and one with a multitude of them. “No one I spoke with knew anything about the medallion,” she said finally. “Of course, this is a town with a high turnover, save for the’ Loons and the Terrans, and jawharries have come and gone since she passed through.”

“Moosers,” said the scarred man, staring into his whiskey. “They call us moosers here.”

“I thought it was ‘coffers.’”

“Everyone is a coffer —or a gull , they use the two terms interchangeably—but they have a special term just for Terrans. Because their holy books say we once abandoned them. A mooser is ‘one who submits.’ Submits to whom, and how that constitutes abandonment, no one will say.”

“Their holy books…”

“…are forbidden to others to read. The Birakid Shee’us Nakopthayiní and the Asejáhn Robábinah.”

“The first one sounds almost like Gaelactic. The ‘specklings down of the headmen.’”

“That’s what most headmen do. Speckle down on the rest of us.”

“The burial chamber of the king, out in the Cones, is called the gáván gofthayin . Sounds like it might be related.”

“‘Loonie headmen. Kopthayini. Gofthayin. Capitàn. Who cares? Shaddap, Pedant.” The Fudir gripped his head in both hands. “All these years, he’s silent. Now he won’t be quiet. Jabber, jabber, jabber. Yes, you!”

If Méarana understood the linguistic shifts that had taken place, then gáván must have once been kábán , meaning a “hut.” So, the burial chamber of the king was the “hut of the headman.” But when she mentioned this pleasant deduction to the Fudir, he shook his head.

“Please, missy. This ples nogut by Terries. Very budmash. We go from here jildy.” Then, dropping the patois, he added, “But I wouldn’t mind getting my hands on a copy of their sacred books. Find out what drives these’ Loons crazy against my people.”

“And yet they produce decent harpers,” said the harper. “The’ Loons do. And they’ve learned the Auld Stuff. The aislings and the airs. I’ve heard them when I’ve gone by’ Loontown. No geantraí, though. I’ve heard no geantraí.” She glanced at the placard above the servers bar—the harp and crescent moon—and wondered what it meant. “Have you ever seen the Cones?” she asked. “There was something in their appearance against the western sky, something ancient and forlorn.”

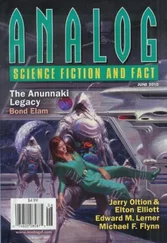

Читать дальше