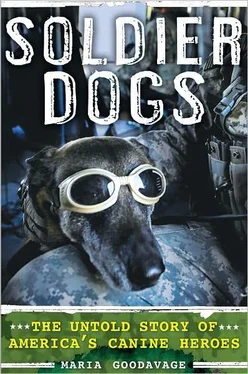

And it just so happens that dogs may be the only “equipment” that get tattoos.

Of course, handlers see their dogs as anything but equipment. Handlers put their lives on the line for their dogs, and the reverse is also true. During the Korean War, the handler of a dog named Judy was taken prisoner and forced to march for two days to his place of detention. When he got there, he unleashed Judy and begged her to run, hoping she’d make it back to HQ. But she stayed at his side. The next day Chinese guards took them to a kitchen and made him tie Judy to a post and leave her. They asked him who Judy was, and he told them she was a mascot.

“I heard a gunshot. I am sure it was Judy,” he wrote.

When soldier dogs and handlers deploy, they spend almost every hour together. Like Donahue and Fenji, they rarely leave each other’s side when they’re at war. Handlers can end up developing a closer bond with their dogs than they do with other people, even spouses. When a handler and his dog have to part from each other in order to fulfill a unit requirement, it can be enough to bring the handler to tears, and to cause a dog to ignore his new handler—at least for awhile.

I’ve never seen anyone cry when she talks about turning in her old rifle or giving back her body armor. The fact that dogs are still considered equipment seems rather antiquated. Sure, they’re not human soldiers, but they’re a far cry from a rifle or a helmet or a helicopter. Ask any child who watches Sesame Street which of these things does not belong, and the tot will point right to the dog. Most instructors and trainers will, too.

“I try to articulate that a dog is not a piece of equipment, but a working, breathing animal that needs to be treated respectfully and kindly,” says Arod, who also runs Olive Branch K-9, a police and military dog consultancy. “Your dog is your partner and values meaningful interaction. You just don’t think about equipment in the same way.”

Some handlers I’ve spoken with hope that at some point four-legged warriors will be given a new designation. Even something like “animal personnel” would be more accurate than “equipment” and would take dogs out of the “thing” category. Dogs could be joined in that category by other animals used by the military, like the sea lions, dolphins, and whales used by Navy SEALs to find sea mines and enemy divers.

In this book, you’ll notice that in most cases where I mention a dog’s name for the first time, it’s followed by a letter and three numerals. That’s a dog’s tattoo number, his unique ID, inked inside his left ear. If you view a dog as equipment, it could be like his VIN. If you see a dog as something more, think of it as his last name.

Here’s a way to use a dog’s tattoo number to win a bar bet with a handler. You can tell a handler what year his dog arrived at Lackland Air Force Base—where young future military working dogs go for processing and training—just by knowing the first letter of the tattoo. Even most handlers I spoke with weren’t sure how their dogs came by their tattoo numbers. But it’s fairly simple.

Tattoos start with a new letter every year. The year 2011, when I arrived at Lackland Air Force Base, was an R year.

So let’s say you come upon Handler Joe and his dog Bella M430. Tell him you can guess pretty close to when his dog arrived at Lackland for the first time. Then all you have to do is figure out how many letters earlier than the current year’s letter M is. If you’d met Joe and Bella M430 in 2011, during the R year, you’d calculate the numerical difference between M and R. So M-N-O-P-Q-R—that’s six letters. But don’t blurt out that Joe’s dog arrived five years ago. The letters G, I, O, Q, and U are not used in tattoos because they can easily be confused for other letters or numbers. So in the case of Bella M430, you “add back” two years (for O and Q) and now you can safely say that Bella arrived at Lackland for processing three years ago. Since most dogs get to Lackland when they’re two or three, you could take it a step further and figure that Bella is five or six years old.

Beers all around!

I’m not sure how much Sergeant Stubby had to do with this, but a military myth holds that a dog is always one rank above his handler. The popularity of this story spiked after the bin Laden raid.

The truth is that, officially, dogs hold no rank—equipment never does. (Equipment doesn’t let you bury your face in its fur when you’re mourning a fallen comrade, either.) It would also be confusing when a dog gets transferred between handlers of different ranks. There would be a lot of demotions and promotions in a dog’s career—not that the dog would care.

That’s not to say that some handlers don’t refer to their dogs as the next rank up. I’ve never come across a marine handler who did this, but it’s a fairly strong tradition in the army, where it probably started during World War II. Some say it was a move to get handlers not to abuse their dogs, because they could be in trouble for abusing a superior. Others believe it was just a maneuver to warm the hearts of Americans so they’d support the war-dog program and donate their dogs to the fight.

Even in army ceremonies honoring a dog for his service, the dog will often be referred to by his rank. And handlers have fun with it in everyday life, too.

“On occasion we tease lower-ranking soldiers if they ask to pet our working dogs,” says Army Sergeant Amanda Ingraham. “We tell them if they do pet our dogs, they need to do so at the position of parade rest and show our NCO some respect. It’s all in fun, but at the same time it gets everyone to realize the value of our dogs.”

And non-handlers will also notice the names of dogs tattooed on their fellow servicemen’s arms or legs.

Ink all around!

6

6

HEY, IS THAT 600 ROUNDS OF ANTIAIRCRAFT AMMUNITION?

Early in the research for this book, I got a note from Brandon Liebert, a former marine sergeant who had been a handler and trainer for eight years. He deployed to Iraq in 2004 with one of the first groups of garrison handlers sent into a war zone. He’s now a civilian contractor, working as a dog handler. He gave me one of my first insights into who dog handlers are.

Dear Maria,

During my time at MCAS Cherry Point, NC (March 2003–August 2006), I only handled one dog. His name is Monty E030, a Patrol Explosive Detector Dog. He and I had a great bond. He was a very fast learner and loved to please me. Because I trained him to do more than what the military required, I ended up making sure he had a different toy for every task. He also had his personal toys. He had more toys than any other dog in the kennels. Every morning we would go out and play before starting any type of training. Even though we were not supposed to, I would feed him some human food while we would be out on patrols. While deployed to Iraq, I would take Monty with me everywhere (i.e., chow hall, internet cafe, phone center, etc). Taking him with me everywhere also helped in keeping up the morale of the troops. They loved to play with him, pet him, help me with his training. Having him around all the time was not only fun and good times for me but also the troops, whether it was on base or out in the field.

When we were in Iraq, we celebrated the Marine Corps Birthday. The Marine Corps flew in steaks for us. I asked the cooks if they would save a leftover one for me so I could give it to Monty, and they did. So we both had steak for the Marine Corps Birthday. He sure did love it.

Читать дальше

6

6