HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperElement 2014

FIRST EDITION

© Charlie Connelly 2014

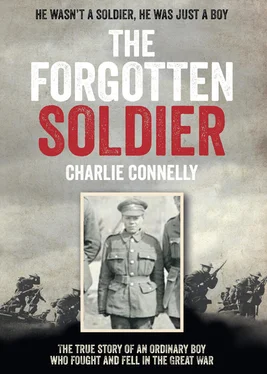

Cover layout design © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2014

Background photograph © Imperial War Museum

Charlie Connelly asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780005784628

Ebook Edition © October 2014 ISBN: 9780007584635

Version: 2014-10-08

For Edward Charles Manco

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

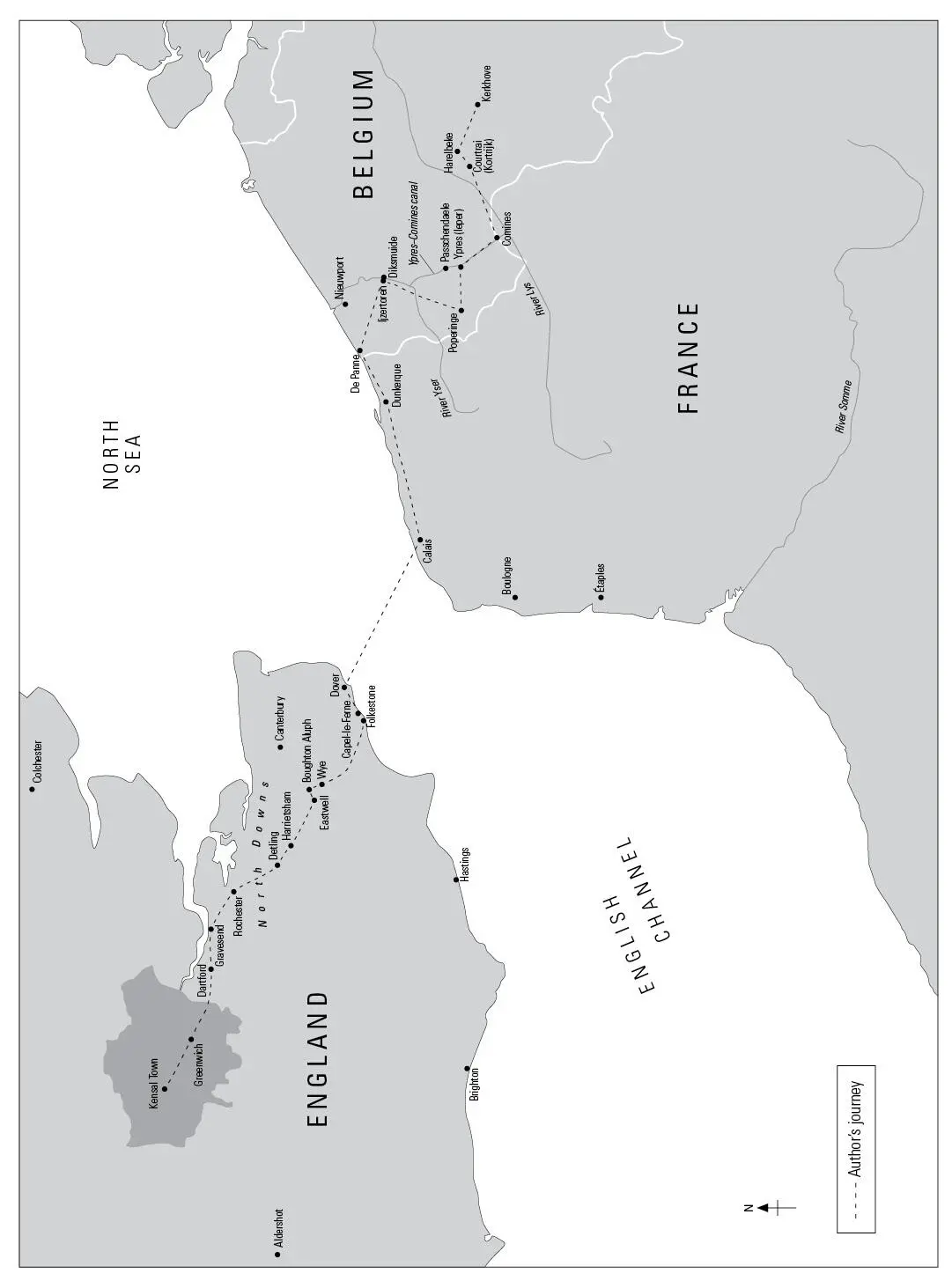

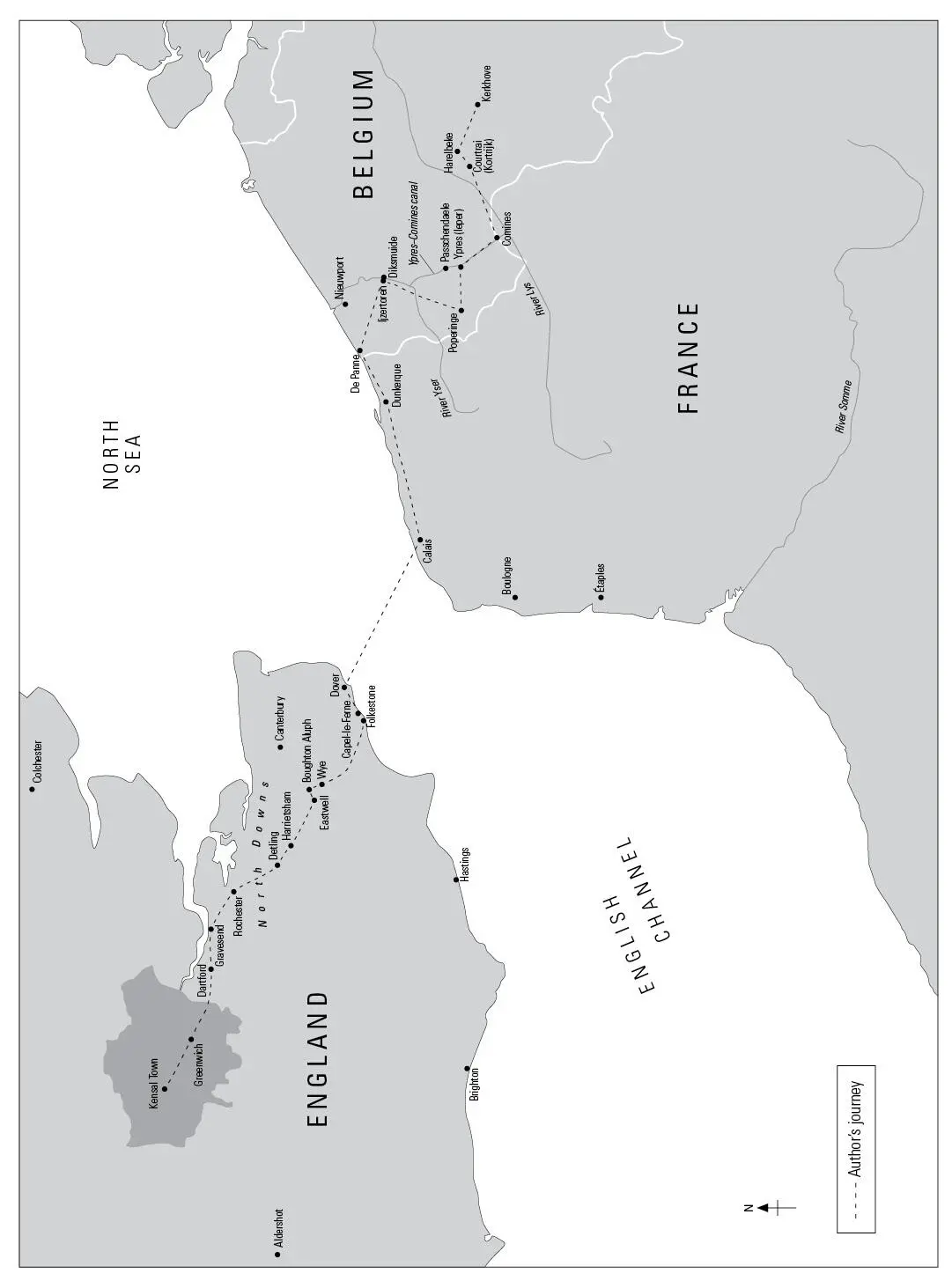

Map

1. ‘A shadow flitting on the very edge of history’

2. ‘The boy from Soapsuds Island’

3. ‘A long, hard journey through a short, hard life’

4. ‘A half-deaf kid from the slums of Kensal Town’

5. ‘I was at lunch on this particular day and thought, I suppose I’d better go and join the army’

6. ‘I am the King of England today, but heaven knows what I may be tomorrow’

7. ‘In the event of my death …’

8. ‘If you are not in khaki by the 20th, I shall cut you dead’

9. ‘I was seventeen years old and already I was well acquainted with death’

10. ‘Though many brave unwritten tales, were simply told in vapour trails’

11. ‘When we got to him all his insides were out. He had a girl’s face. He was ever so young’

12. ‘A boy of eighteen, looking around at the sea of faces that seemed so assured’

13. ‘It used to make me cry sometimes to see a big man like that grovelling for a little bit of bread’

14. ‘I am troubled with my head and cannot stand the sound of the guns’

15. ‘We used to sit in the corner of the trench and think about it: we’d say, all this going on, is it worth it?’

16. ‘The farmhouse had taken the main shock of the blast, but the shack with the two girls in it had completely disappeared’

17. ‘I wasn’t scared advancing. As far as I remember there was just a blind acceptance that we were going forward and that was that’

18. ‘The surgeon couldn’t find the bullet and I was in agony, so they gave me a cup of tea and gave me heroin’

19. ‘If Edward was everyman in the First World War, equally he was every ordinary man who’d fallen in battle over the centuries’

20. ‘I felt it was a great responsibility leaving eighty women and children behind to die with nobody looking after them, but there it was’

21. ‘During that last half hour before the armistice, a corporal who was with us got shot, in that half hour, right at the end of the war, and he’d been in it since 1914’

22. ‘The ghosts of the people who never were’

Bibliography

Author’s Note

Exclusive sample chapter

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

Write for Us

About the Publisher

1

‘A shadow flitting on the very edge of history’

I didn’t know it at the time but the silence on the other end of the line was the silence of nearly a century.

I’d been researching the family tree and was proving to be barely competent as a beginner genealogist. That said, I’d somehow managed to barge my clumsy way back through the records as far as the beginning of the twentieth century, and I was on the phone to my dad to update him on some of the things I’d found.

‘… So, yes, North Kensington was where your grandparents were living at the time, just by Ladbroke Grove,’ I said. ‘Oh,’ I added, almost as an afterthought, ‘and I’ve also found your uncle Edward who was killed in the First World War.’

Silence.

‘I didn’t know anything about that,’ said the quiet voice at the other end of the line.

Private Edward Charles John Connelly of the 10th Battalion, Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment was killed in Flanders on 4 November 1918. He was nineteen years old. Edward was my grandfather’s elder brother, my father’s uncle, and here was my father telling me that he didn’t even know he’d had an uncle Edward.

How could it be that my dad, who was given the middle name Edward when he was born more than two decades after Edward Connelly’s death, had never been told about his own uncle? Dad had always told me that his father, who was barely sixteen years old when the Great War ended, had lied about his age and enlisted, but never spoke about what he experienced. To think that included the actual existence of his brother, however, seemed an extraordinary thing.

But then, my grandfather’s reticence was not unusual. It’s something you hear quite often about men of that generation: how the things they saw and experienced had been so traumatising that they’d compartmentalised their memories and sent them away to somewhere in the furthest wispy caverns of the mind, never to emerge again. My grandfather was to all intents and purposes still a child during the war, yet he’d been to a place about as close to hell on earth as anyone could imagine. Is it any wonder that he wasn’t chatting amiably away about it at the kitchen table while filling in his pools coupon? Maybe in there, enmeshed among the memories and experiences that he’d closed away for ever, was his own brother who’d gone off to war and never come home. Maybe he’d felt some kind of survivor guilt – that the boy who really had no business being there in the first place had returned but his big brother never did, never had the chance to marry and have a family, to have a long and busy life and leave a legacy of memories and experience that would succeed him for generations.

Maybe this was how Edward Connelly fell between the cracks of history and the fissures of memory to lie forgotten in the Belgian mud for the best part of a century. Perhaps this is how the silence fell over a boy sent off to war, to die in a strange country at the arse-end of a horrendous conflict that was effectively all over, pending official confirmation from a bunch of paunchy bigwigs with fountain pens in a French railway carriage a week later. The mystery of the forgotten soldier in the family history was one that would come to intrigue me more and more.

Of all the pointless deaths of the 1914–18 conflict, Edward Connelly’s seems more pointless than most. The war on the Western Front was all but over, and the armies were effectively going through the motions. By 4 November 1918 the outcome was beyond doubt: the Germans had gambled everything on their spring offensive earlier in the year and, despite making significant territorial gains, had been forced back way beyond their original lines and all but collapsed. Morale at home and on the Front had imploded. The money was running out. The game was up. The last couple of weeks before the armistice were pretty much token efforts at attack and defence, largely spent with the Allies chasing the retreating Germans across the Belgian countryside towards Germany.

Читать дальше