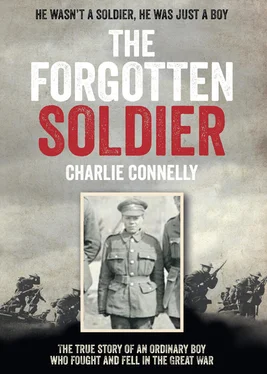

One of those token efforts killed a token soldier: Private Edward Connelly, a nineteen-year-old railway-carriage washer from West London.

I knew nothing about him or the circumstances of his death, but it all seemed so pointless and unfair and I wanted to know more. I tried to find out as much as I could about Edward Connelly to fill in the uncle-shaped hole in my dad’s life, but it soon became clear there really wasn’t much to go on. There was a birth certificate dated 25 April 1899. I found a baptism record. He appeared on the censuses for 1901 and 1911 as a two-year-old and a twelve-year-old living in North Kensington in London. There was an entry in ‘Soldiers Died in the Great War, 1914–1919’ and a record of his grave at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. And that was it; that was all I could find.

There isn’t even a service record for him covering his time in the 10th Queen’s. These are often full of extraordinary detail, from the soldier’s physical appearance to their medical records and accounts of breaches of discipline and their attendant punishments, but around two thirds of these individual soldier files from the First World War were destroyed during the Blitz. Edward’s was one of them. The forgotten soldier was doing a flawless job of being forgotten.

Beyond these scant pieces of information Edward Connelly left nothing behind when he fell in the Flanders mud that cold November day in 1918, and within a generation all those who had known him and could remember him were dead. It was almost as if he died with them a second time.

As time passed I grew more and more uncomfortable about the way Edward had vanished from history. I began to feel ashamed that we didn’t know who he was, and angry that his life had been snuffed out in such a pointless way – a week before the armistice, for heaven’s sake. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the war itself, at least if he’d died at Passchendaele or the Somme there would be a sense that he had been fighting for something. The date of his death just made things worse: not only had he been forgotten, but his death had been for nothing.

Having rediscovered him, I began to feel responsible for his legacy, or lack of it. I wanted to find out more about his life and how, where and why he died. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission he was buried at the Harlebeke New British Cemetery near Courtrai (the French spelling of modern Kortrijk), close to the Franco-Belgian border. What was he doing there? Where had he been? How did a teenager from an Irish immigrant family in the poorest part of North-West London come to be a private in the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment and die in a futile battle in the final twitching throes of the First World War?

I resolved to find out, but given the dearth of records available I wasn’t just beginning from a standing start, I was practically standing on one leg.

For one thing, although I studied history and have written about it for a living, I’d never been remotely interested in war or military history. At school we’d covered the causes of the First World War in our history lessons, but given that I had spent most of them alongside Tim Bennett at the back of the class drawing recreations of the weekend’s better First Division goals in our exercise books, not many of those causes actually went in.

One November an elderly maths teacher who had fought in the Second World War addressed our morning assembly on the last Friday before Remembrance Sunday. It was one of the rare occasions that we all listened, as he described how if every British man killed in the First World War marched two by two in through one door of the building and out through the other at regular military marching pace, twenty-four hours a day without break, it would take three weeks for every dead man to pass through. That was something that stuck.

Studying the war poets piqued a little interest. We were handed a collection called Up the Line to Death , which made an impression on me in that I could remember some of Wilfred Owen’s famous lines, mainly because they struck me as so anti-war in sentiment. I had no idea at the time, of course, but Owen was killed on the same day as my great-uncle, a few miles further south.

I knew names like the Somme, Ypres and Passchendaele but wasn’t entirely sure why. I’d laughed at Blackadder Goes Forth and been struck dumb by its poignant final scenes. I’d buy a poppy if I saw one and observe the minute’s silence in front of the television every Armistice Day, but that was about it.

In Sarajevo I stood on the exact spot from where the Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip fired the shots into Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sofia that killed them both and pushed over the first domino in the chain that led to the largest conflict the world had ever seen, and found it strangely underwhelming. I was more interested in the scars left by the most recent Balkan conflict, which were still evident all around the city, from the shrapnel spatters in the plasterwork of just about every building to the red resin Sarajevo Roses in the streets that filled the star-shaped shell scars from the artillery that had rained down on the city during the siege of the early nineties. This had been a war from my lifetime, one I’d seen on news bulletins as it happened. The First World War seemed so distant; there was nothing in Sarajevo to evoke it for me. Even as I stood on the noisy, fumy Bosnian street corner where it had all started, the First World War remained purely one-dimensional, tangential at best to everything in which I was actually interested.

Stumbling inadvertently across my great-uncle Edward changed that. I couldn’t stop thinking about him, what he might have been through and about how unfair it was that he’d been entirely forgotten. I found myself feeling angry at the pathetic, pointless waste of a young life, and guilty that he’d been expunged from the family narrative. With the deaths of its last survivors still comparatively recent, it’s not long since the First World War passed from memory into history, yet for me it was trying to move in completely the other direction.

I was confused as to why Edward’s death might be affecting me more than any of the others that I found in my family research. There were a number of early deaths equally as tragic and untimely: I’m descended from dock workers, with all the attendant accidents and disease that went with that line of work and the way of life that went with it. I had ancestors killed on quaysides and dying young from diseases and medical conditions that are entirely preventable today: my grandmother’s tuberculosis, my uncle Eric, who died from gastroenteritis at the age of eight months in the 1930s, surely equally as poignant, equally as tragic?

But Uncle Edward’s death in battle came to dominate everything else I’d found. Why should death in combat be any different from other untimely Victorian and Edwardian demise? Why should that be?

War, whether necessary or not, is humanity at its worst. Sometimes it can bring out the best in humanity: compassion, courage and selflessness, but the unimaginable horrors thrown up by the arrogance of certainty are an awful way to resolve awful situations. I can’t bear conflict of any kind. I’ve not been in a fist fight since a disagreement over a cup of tea with Gary Wayman when I was fourteen, and even then I’m not sure he noticed. Maybe Edward Connelly’s death stood out because war is such an alien concept to me, and I was imposing myself on his experience, wondering how I’d have coped, if I’d have coped. The thought of having to create enough hate and aggression to be able to kill a person is a bizarre one – even if it is based on the grounds that if you don’t kill them they’re probably going to kill you – especially if, like me, you’re a yellow-bellied scaredy-cat. And maybe there lies the rub.

Читать дальше