Art, music, exploration, literature, sport, science, imperialism: as the nineteenth century eased towards its close, the themes that had defined it were preparing to push on into its successor. All of this was happening a long way from Gadsden Mews in North Kensington, however, where Edward Charles John Connelly was born to George and Marion Connelly ten months after their marriage the previous year.

Mews properties may sound quite fancy these days, but as London slums went Gadsden Mews was among the worst. It was a small, cramped, overcrowded clutch of dingy tenement buildings squeezed into a tiny space to the rear of other streets of slum housing, the centre of a triangular street pattern that began with the borders of the Great Western Railway to the north, the Grand Union Canal to the south and east and Ladbroke Grove to the west and shrank concentrically to the cramped, claustrophobic dankness of Gadsden Mews. Victorian poverty campaigner Charles Booth noted around the time of Edward’s birth that Gadsden Mews was ‘very poor looking, dirty, grimy’. The area had grown up rapidly from the 1840s with the coming of the railways and the canal, to become known as one of London’s worst slums. So many women worked as laundresses – including Edward’s mother and grandmother – that the area became known as ‘Soapsuds Island’. Charities including the Protestant missions did their best to alleviate some of the poverty, but it was a losing battle. This was the world into which Edward Connelly, the boy from Soapsuds Island, was born.

In many ways Edward was a product of the century that was ending as he entered it. He came from Irish stock: his great-grandfather John and great-grandmother Catherine had come to London from a small townland outside Youghal in the east of County Cork in 1842. It was just before the Great Famine, but there had been a number of smaller famines at the time and the Connellys were living in a tiny one-room house, trying in vain to live off the land. John, as the eldest, had to leave to make one less mouth to feed. He took advantage of a price war between steam packet companies to find a cheap passage on the crowded deck of a boat that docked at Shadwell in East London some time in 1842, where he and Catherine would live in various tenements for the rest of their lives while John got what work he could ‘on the stones’ at the docks until his death from tuberculosis in 1890 at the age of sixty-five. The desperate times are no better demonstrated than by the four months’ hard labour John did in Newgate Prison in 1852 after he was caught selling watches stolen from the hold of a ship on which he was working.

Around 1890 Edward’s father George moved from the East End to the burgeoning North-West London Irish community in search of work on the railways. While living among Irish immigrants in Admiral Place, a stone’s throw from the mews in Kensal Town, he courted an English girl living in the same building; they married and the newlyweds took a room in Gadsden Mews as their first marital home.

Marion Christopher, Edward’s mother, came from Dorset agricultural stock. The Christophers had lived for many generations in and around Blandford in Dorset, never owning land but always working it. Her parents joined the increasing migration from the uncertainty of the countryside to the greater employment prospects of the cities at the height of the Industrial Revolution, making the long journey from rural Dorset to the tenements of West London in 1874. Marion was the first Christopher to be born among the cramped, dirty streets of North Kensington, in the summer of 1877 to George and Mary Jane Christopher. George had been in the Royal Artillery for a period as a younger man, but on moving to London he found himself getting whatever labouring work he could.

At the time of Edward’s birth, Marion’s younger brother Robert Christopher had just left for the Boer War as a soldier with the 2nd Battalion of the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment, the same regiment that Edward would join eighteen years later. Robert had enlisted the previous year at the age of seventeen and would spend three years fighting in South Africa before being wounded and sent home to England in 1902. When the First World War broke out he was labouring in a power station, but his previous military career led to him being recalled to the army as a private in the 6th Battalion of the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment. Robert Christopher died of wounds sustained in a raid on German positions at the Hohenzollern Redoubt near Bethune on 5 April 1916.

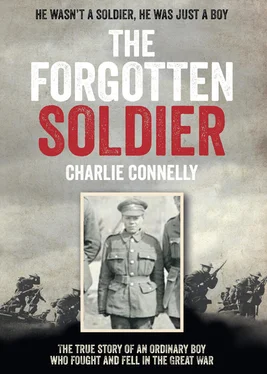

Born to Irish immigrants on one side and refugees of the Industrial Revolution on the other, Edward was an archetype of the late-nineteenth-century urban working class. His and their worlds were small, their horizons narrow: both families lived for more than half a century within the same tiny network of streets in North-West London. It was from there that I would set off on my journey to find the forgotten soldier.

3

‘A long, hard journey through a short, hard life’

One hundred and fifteen years after his birth, almost to the day, Edward Connelly’s locality looked quite different to the one he knew, especially on one of those spring mornings that make even the Harrow Road happy. There was the cheeriness of renewal everywhere – a freshness in the air; even the rattling rasp of the grilles going up at the bookmakers and money-transfer shops seemed to have a tangible jauntiness. The half-dozen people waiting for the post office to open smiled and chatted. Two men in bright-blue overalls with the legend ‘Love the Town You Live In’ written on the back of their hi-vis vests rumbled by, wheeling a bin full of brushes. As the sun climbed higher into the sky and forced the shadows into retreat towards the shop fronts, a young woman wearing a puffa jacket waiting in the post-office queue put her head back, closed her eyes and smiled to herself as the sunshine warmed her face. The sky was deep blue and cloudless, bare save for the swollen ghost of an aircraft contrail.

I ordered a cup of tea in a café, sat down at a Formica table, reached into my bag and pulled out a dog-eared copy of the London A–Z along with a folded map: a reproduction of an Ordnance Survey of the area from 1913. I found the right page of the A–Z and opened the old map, placing them side by side on the table, two landscapes divided by a century but whose urban contours made them recognisable as the same place. I ran my forefinger down the page of the A–Z and then did the same to the map until I found where I needed to go.

On the old map, Gadsden Mews is there in the east of Kensal Town, a wedge of North-West London still hemmed in today by the canal, the railway and Ladbroke Grove. Within this triangle on the old map, concentric streets of tightly packed houses shrink towards the very centre where, shoehorned into a cramped space between the backs of the residences, there are two rows of tiny squares named Gadsden Mews. There’s no Gadsden Mews on the A–Z , it’s long gone, but the surrounding streets survive and I could at least get close if I could find Hazelwood Crescent.

I drank my tea, headed back out into the sunshine, turned east along the Harrow Road, crossed the bridge over the canal and walked towards where Gadsden Mews used to be.

After crossing the canal I headed for the landmark of Erno Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower until I found Hazelwood Crescent nestling in its considerable shadow. The entrance to Gadsden Mews had been at a slight dog-leg kink in Hazelwood Crescent that’s still there today, so I’d be able to pinpoint almost exactly where the mews once lay. The streets were quiet as I reached the hint of a bend I was looking for. On this spot had been the only way in and out of the slum tenements, the tiny three-storey wooden houses packed with the poorest of the poor, where whole families often lived in single rooms with little in the way of comfort or sanitation. Kensal Town itself was a poor area, but even Kensal Towners would probably have looked down on Gadsden Mews.

Читать дальше