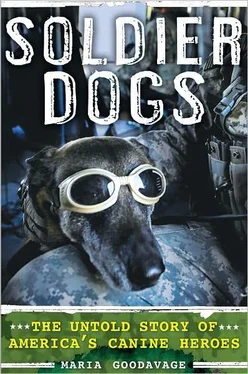

And that marked a hiatus in the military’s dog program. The procurement stopped. The army war-dog program was defunded, and rumors spread that the program would be abandoned entirely. This drew an emotional, angry public response. The program survived; the air force took it over and started a training center at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas.

But in the late 1950s and early 1960s, as America’s involvement in Vietnam intensified, and as the air force began to see the labor-saving advantages of sentry dogs, demand outstripped supply. Moreover, there was no military pipeline, or even a civilian pipeline like Dogs for Defense, to bring more dogs to the effort.

The result was that the military was forced into a hurry-up scenario, and quickly sent out small teams of recruiters to bases around the country to buy up dogs from neighboring communities. The price paid was usually not more than $150 per dog. The breeds of dogs procured once again expanded, and Labradors and even hounds were among those drafted. Some 3,800 dogs would serve during the course of this war.

War dog procurement is partly a matter of selecting breeds for combat and then drawing a steady supply, but it’s also a matter of demilitarization and repatriation. That was assumed after World War II but forgotten after Vietnam, when thousands of dogs were left behind, either to replenish supplies for the South Vietnamese Army or to be eaten, as some have asserted, or simply euthanized. Some handlers even chose to reenlist so they could be with their dogs as long as possible, in hopes they might be able to prolong the dogs’ lives and perhaps even adopt them.

The situation now is utterly transformed. Our understanding of dogs’ qualities and abilities is far better, and the results of our working together in the military are vastly improved. So does this new kind of military use have anything to offer back to our understanding of, or relationship with, our own dogs at home?

4

4

JAKE, THE EVERYDOG WITH THE RIGHT STUFF?

I’d written about other military working dogs before Cairo and Sergeant Stubby. And every time I did, I found myself looking at my own dog.

In the haze of glory surrounding military working dogs, my dog Jake, who is now nine, doesn’t really look like a contender for admission into the military elite. When he was younger, did he have what it took to sniff out bombs, to risk his life, to walk point in order to save others? I’d look at him, typically lying around sleeping somewhere and perhaps snoring, or absconding with an unattended bit of food, or rolling in the grass. Not obviously military hero material.

But Jake does have his breed going for him. He’s a Labrador retriever—a breed the military commonly uses for detection work. Actually, we’re not 100 percent sure he’s all Lab. He was found wandering the streets of a seedy part of San Francisco at six months of age. A rescue group took him in and we agreed to foster him. It was to be just for a week or two. Our old Airedale had died the previous month, and we weren’t ready for a dog to take up a full-time, permanent position in our house. This was to be a temp gig. But the minute he walked in the door, on December 1, 2002, I knew we were in trouble. He was all paws, with a big smile on his wide blond face, and bright brown eyes that scanned the foyer, looked at me, and gave me that “Yup, I’m home! Get used to me!” look.

Jake does show some signs of being a good potential war dog. He bonded with us quickly, he is eager to please, would do anything for us (except stop chewing flip-flops), and is pretty fearless. He’s also a great sniffer. I have yet to find a place to hide his dog treats where he doesn’t sit staring at the invisible wafting scent, obsessed, clearly trying to figure out ways to maneuver them down from their stealth position, and often succeeding.

But military dogs have something Jake doesn’t: a job. It’s something dog experts say is lacking with many pet dogs today, and is at the root of many problems. Boredom can lead to destructive or anxious behavior. At best, it’s just not much fun.

“Dogs used to have jobs; that’s what they were trained to do,” dog trainer Victoria Stillwell, host of the Animal Planet show It’s Me or the Dog , told me when I ran into her at an event honoring hero dogs in Los Angeles. “Now these poor animals spend most of the time sitting on the couch, alone all day. They’re bored. We need to give them jobs. If they’re motivated by them, if they enjoy themselves, life is better all the way around.”

I started to feel bad that Jake didn’t have a job, but then I realized he’s like me. He’s kind of a self-employed freelancer. He finds work that he’s passionate about and puts everything into the job until his mission is accomplished.

His current gig is rather cliché: He lies in wait in our backyard much of the day, so he can chase a relatively new neighborhood cat, Kika, out of the yard when she ventures over the fence. (He never gets closer than several yards from the cat, or I’d put the kibosh on it.) She’s a beautiful, lithe, leopard-spotted feline, and I welcomed her into our yard until I saw her chasing and killing butterflies, and until I found out why my little writing cottage smelled like a litter box every time I opened the front window. (She was using the bit of dirt right outside my window as her toilet.)

When Jake is in the house and he hears her little bell, he races down the stairs and out to the backyard. When he runs after her, he looks more like a rocking horse, cantering merrily, tail woggling quickly from side to side and up and down. He doesn’t seem to take the chase too seriously. A big woof or two and Kika is out of the yard through a hole in the lattice of the back fence. Only then can Jake rest, a job well done.

Jake is an Everydog. His is the most popular breed of dog in the United States. He’s even got one of the most common names for male dogs. And his passion for chewing shoes and chasing cats and finding food are charmingly stereotypical.

He pokes around in this book. You can think of him as a stand-in for your dog or other pet dogs if you find yourself wondering, as I did and still do, how the average dog would fare in the military.

Having an Everydog in the mix puts war dogs into perspective. Military dogs may have unique breeding and intense training, but underneath it all, they’re dogs. Unless they’re of the super-aggressive variety, many go on to become pets at the ends of their careers. (A huge improvement from post-Vietnam days.) Inside, most probably just want to catch a ball and get a pat for a job well done, eat some good grub, and sleep in a comfortable bed near their favorite person.

Most maybe. But “some dogs are just jerks” I was told by an air force technical sergeant who has worked with every type of dog during his decade in the world of handlers. There are the dogs, for instance, who will seem to reach out to you and beckon you to pet them, but once you do, they try to bite your hand off. “They get this look in their eye like ‘Heh heh heh,’” he said. “Just like people, some dogs are bad guys.”

5

5

THE MEANING OF MILITARY DOG TATTOOS

Military working dogs are considered equipment by the Department of Defense. In some ways, they’re officially looked upon as a rifle or a minesweeper would be. It’s a designation that fell upon military dogs after World War II, when the military stopped borrowing dogs from Mom and Pop Dog Lover and started buying dogs.

Читать дальше

4

4