No. The answer is no: there is no one else on their side. Or that is at least the self-pitying answer that Adolfo Suárez undoubtedly gave to himself at that moment and the self-vindicating answer he was still giving years later, when he told the anecdote about his friend, now dead (and perhaps for that reason he was telling it). But, even if it was self-pitying and self-vindicating, the answer was not false.

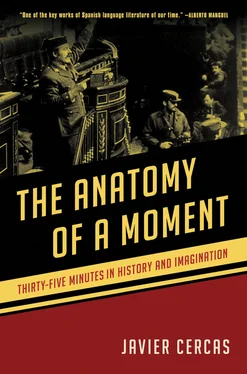

The image of Adolfo Suárez sitting alone in the Cortes chamber during the evening of 23 February is also an emblem of something else: an emblem of his virtually absolute solitude in the months leading up to the coup. Curiously, a year and a half before that date a photographer caught a similar image in the same place: sitting on his Prime Minister’s bench, Suárez is dressed the same way he was on 23 February — dark jacket, dark tie, white shirt — and, although his posture is a little different from that which he adopted while the guns were firing on 23 February, to his right stretches the same desolation of empty seats. As in the image of 23 February, Suárez is posing; as in the image of 23 February, Suárez doesn’t appear to be posing (Suárez was always posing in public: that was his strength; he often posed in private: that was his weakness). The image was taken on 25 September 1979, but, if we ignore certain differences of colour and framing, it could be confused with that of 23 February 1981, as if, instead of photographing Suárez, the photographer had been photographing the future.

Although the secret was not made public until a year later, in September 1979, when he was at the height of his power and his prestige, Suárez was already privately finished as a politician. Earlier I

pointed out one reason for his sudden collapse: Suárez, who had known how to do the most difficult thing — dismantle Francoism and construct a democracy — was unable to do the easiest: administer the democracy he’d constructed. I’ll qualify that now: for Suárez the most difficult was the easiest and the easiest was the most difficult. It’s not just a play on words: although he hadn’t created Francoism, Suárez had grown up with it, he knew its rules inside out and managed them masterfully (that’s why he was able to finish Francoism off, pretending he was only changing its rules); whereas, although he had created this democracy and established its rules, Suárez had difficulty managing within it, because his habits, his talent and his temperament were not made for what he’d constructed, but for what he’d destroyed. That was at once his tragedy and his greatness: that of a man who consciously or unconsciously works not to strengthen his positions, but rather, to resort to Enzensberger’s term again, to undermine them. Since he didn’t know how to use the rules of democracy and only knew how to exercise power the way it’s exercised in a dictatorship, he ignored Parliament, ignored his ministers, ignored his party. In the new game he’d created his virtues rapidly turned into defects — his savoir-faire turned into ignorance, his daring to rashness, his assurance to coldness — and the result was that in a very short time Suárez was no longer the brilliant and resolute politician he had been during his first years in government — when everything in his head seemed to connect with everything else, as if he had a magnet inside him that attracted and ordered the most

insignificant fragments of reality and allowed him to operate without fear, because at each moment he had the certainty of knowing the most distant result of every action and the innermost cause of every effect — but became a clumsy, dull and hesitant politician, lost in a reality he didn’t understand and unfit to manage a crisis his bad governance did nothing but deepen. Together with the jealousy, bickering and greed for power of the ruling class, these deficiencies triggered the generalized plotting against him from the summer of 1980 onwards that ended up spurring on the coup; together with the exhaustion produced by four incredibly tough years as Prime Minister and a character more complex and more fragile than those who knew him only superficially suspected, they also triggered his personal collapse.

From the summer of 1980 onwards Suárez spent his time practically cloistered at Moncloa, protected by his family and by a meagre handful of collaborators. He seemed to be affected by a strange paralysis, or by a hazy kind of fear, or maybe it was vertigo, as if at some moment of masochistic lucidity he’d understood that he was no more than a fraud and intended to avoid any social contact at all costs for fear of being unmasked, and at the same time as if he feared that an obscure longing for sacrifice was driving him to put an end to the farce himself. He spent hours and hours shut up in his office reading reports relating to terrorism, the Army, economic or international politics, but then he was unable to make decisions about these matters or even to meet with the ministers who needed to make them. He didn’t attend Parliament, didn’t give interviews, was barely seen in public and more than once did not want or could not manage to preside from start to finish over Cabinet meetings; he could not even find the energy to attend the funerals of three Basque members of his party murdered by ETA, nor those of the forty-eight children and three adults who died at the end of October as the result of an accidental propane gas explosion in a school in the Basque Country. His physical health was not bad, but his mental health was. There is no doubt that around him he saw only an obscurity of ingratitude, betrayal and contempt, and that he interpreted any attack on his work as an attack on his person, something that might also be attributed to his difficulties in adapting to democracy. He never fully understood that in the politics of a democracy nothing’s personal, given that in a democracy politics is theatre and no one can act in a theatre without pretending to feel what they don’t feel; of course, he was a pure politician and, as such, a consummate actor, but his problem was that he pretended with such conviction that he ended up feeling what he was pretending, which led him to confuse reality with its representation and political criticisms with personal ones. It’s true that in the hunting party unleashed against him over the course of 1980 many of the criticisms he received were personal rather than political, but it’s no less true that when he arrived in government he had also been the object of personal criticisms, only then the Prime Minister was still protected by the privileges of an authoritarian system and his neophyte enthusiasm turned them into spurs to his will and his mental strength neutralized them, attributing them to failings of their authors — errors of judgement, frustrated ambitions, unsatisfied vanity, bitterness — now, instead, exposed by liberty, submitted to pressing demands and with his defences decimated by the high-interest loan of almost five years of a term of office in often extreme conditions, he felt those personal criticisms to be an instrument of daily martyrdom, undoubtedly because he repeated them to himself, and against oneself there is no possible protection. Like all pure politicians, Suárez also felt an urgent need to be admired and loved and, like everyone in the political village of Francoist Madrid, he’d forged his career to a great extent on the basis of adulation, spellbinding his interlocutors with his sympathy, his insatiable desire to please and his tree-like repertoire of anecdotes until they were convinced not only that he was an extraordinary being but also that they were even more extraordinary than he was, and therefore he was going to make them the object of all his trust, his attention and his affection. For a man like that, all outward appearance, whose self-esteem depended almost entirely on the approval of others, noticing that his conjuring tricks no longer worked must have been a devastating experience, that the country’s ruling class had taken his measure and the shine of his seduction had dimmed, that no one laughed at his jokes or was entranced by his opinions, that no one fell under the spell of his stories or felt privileged to be in his company, that no one believed his promises any more or accepted his declarations of eternal friendship, that those who had admired and flattered him looked down on him, that those who owed him their political careers and had pledged their loyalty betrayed him, that the best feeling he could now evoke among his equals was a mixture of weariness and mistrust and that, as the polls made sure to demonstrate to him daily starting in the summer of 1980, the whole country was fed up with him.

Читать дальше