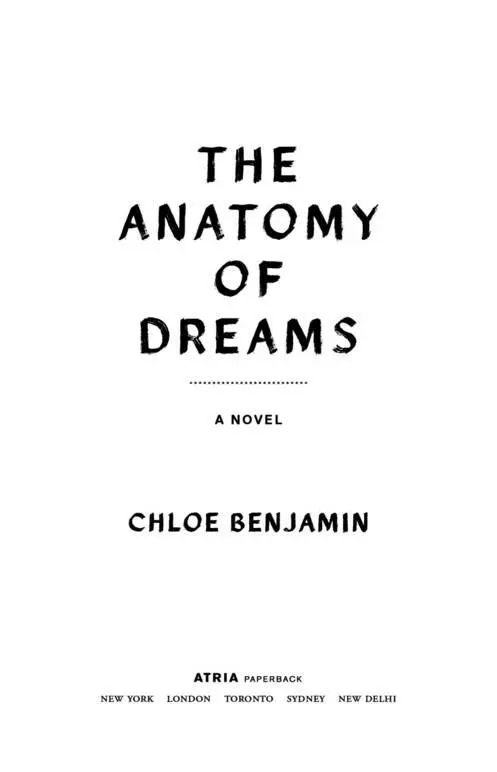

The Anatomy of Dreams by Chloe Benjamin

PART ONE: DUSK

1. EUREKA, CALIFORNIA, 1998

When Gabriel returned to me, I was twenty-one, and I was in the middle of the long summer before my senior year of college. At the time, I was a realist. I was at the top of my class, and I didn’t think there was anything anybody could tell me that I couldn’t figure out myself. Coincidences, accidents: I believed in those. But it took such effort to unfold other possibilities. That meant opening myself like a paper fan, the ridges flattening to reveal parallel worlds.

My first clear memory of Gabe is from our junior year of high school, though I was aware of him before that—you knew everybody at boarding school, especially one as small as Mills. He was part of a rowdy group of boys who were always getting into trouble. Not pranks or fighting—they were just too investigative for their own good, regularly uncovering some conspiracy: what was actually in the cafeteria meat hash, or what Mr. Keller, the headmaster, was growing in the garden behind his house. I didn’t pay Gabe much attention those first few years. I was preoccupied with my courses, especially English; the hard sciences came easily to me, but I couldn’t think in metaphors. Maybe that’s why I was annoyed by Gabe and his friends, for whom one thing always stood in for another: the corned beef in the hash was dog meat, and among the strawberries and celery and mint I had seen with my own eyes, Mr. Keller was growing oleander to make poison.

In our third year, though, a lunar eclipse brought us together. Mr. Cooke, our physics teacher, had been talking it up all semester, and our class had permission to see it. It would be at 6:51 P.M.—dinnertime—but that night we ate outside. It was cold but not snowing: in Northern California, January brought steamy haze that lent each evening a feeling of dark eventfulness. We carried out blankets and trays and huddled at the top of Observatory Hill, where Mr. Cooke had once shown us how to chart the phases of the moon. I sat with Hannah McGowan, my roommate and best friend, who was telling me a story in a rapid, hushed voice and at one point said, “Sylvie. Sylvie . . .” but I could hardly hear her. Her voice trailed into the air like fog as we waited for the moon to change.

Mr. Cooke had told us that a lunar eclipse could only occur when a full moon was perfectly aligned with the earth and sun. For just a few minutes, he said, our planet would cast two shadows and the moon would travel through them. Light from the sun, passing through earth’s atmosphere, would bend toward the moon, and our rock would transform: dyed by the planet’s sunrises and sunsets, the beginnings of days and the ends of them, she would turn red.

I knew all of this, but I was still unprepared for the feeling that came over us when it happened. Slowly, earth’s shadow moved in front of the moon, covering it almost completely. But the moon fought back. Like a phoenix, she shed her ashes and caught fire. We gaped at her change in costume: she hung, a blood orange in darkness. The trees and the sky and even the hill vanished, and we had only each other.

And then, of course, it was over. The moon faded back to gray, and we all laughed in a jittery, scattered way, as if shaking off the remains of a fear. By 9:00, small groups had formed and left the hill. I stayed, along with a few others. Gabe was one of them. As we started to talk, he asked, “Who wants to see something I found?”

There was something bold and vulnerable about him, standing on top of a rock to the left of the group. We looked at him with mild interest and amusement, the deluded but well-loved member of our small town. He was no taller than five feet six inches and slender then, though he became stockier as he got older. He had the square, densely determined face of a pit bull, hazel eyes, and a thick swath of brown hair that whipped around in the wind like a wild halo. Sometimes the girls on my floor gossiped about him, saying he had a Napoleon complex. Now another boy shouted at him to get off the rock. But Gabe stayed, his eyes swooping from face to face like a low bird before landing on mine.

I shivered. Was it dread? Pity? Or perhaps, somewhere, the thrill of election.

“I’ll see it,” I said.

There were whoops and catcalls as we left down the hill, but Gabe plunged silently into the redwoods. The trees surrounded Humboldt County and its bowl of bay, filling our campus with a sweet, grandfatherly smell. I thought of turning back—I’d never had a violation before, and if we were found in the woods, we could both be suspended—but I decided against it. Just as I knew Gabe’s reputation, I knew my own: a goody-goody, uptight, not a daredevil like him and his friends. I found them irritating, sure, but when I watched them laugh raucously at lunch or play soccer before dinner, falling whole-body into the mud, sometimes I wished I wasn’t always a spectator.

We emerged in the clearing beside Mr. Keller’s house. Trespassing here was much worse than being caught in the woods. Mr. Keller was forty-five, a firm-bodied man with a bald head and stark, Germanic features. Besides being headmaster, he taught an upper-level psychology course that people practically fought to get into. Dynamic, creative, and impishly appraising, he demanded more of us than any other teacher. He was the harshest, too.

“Jesus Christ, Gabe,” I hissed.

“Don’t freak out,” said Gabe. “I won’t do anything untoward.”

He said the last word—one of Mr. Keller’s favorites—with special emphasis. The headmaster’s house was a two-story brick structure with small, turreted rooms rising up like pointed attics. But Gabe led us around to the garden, a square plot inside a silver-gray fence. Two stories above us, the tall windows glowed with light. Gabe barely glanced at them before stepping lightly through the unlatched gate.

I edged inside the gate and followed his footsteps—he wound through the plants with such dancerlike precision I suspected it was not his first time there. The sun was long gone. In the moonlight, the flowers and vegetables Keller tended glowed with the otherworldly iridescence of deep-sea creatures.

“Everyone’s probably back in the dorms,” I whispered. “So find whatever you want to show me or don’t.”

“Keep your voice down.” Gabe held my eyes. “Come here.”

He was in the corner of the garden, pointing to a little patch inside the ninety-degree angle of the fence. Below his finger was a flower, large, a fuchsia color so vibrant I could see it in the dark. When I bent closer, I saw it was not one flower but two—or one and a half. The flower had two faces, rimmed with slender pink petals, which shared the same central disk and the same stem. What was notable about the disk—that saturated, mustard-colored eye—was that it looked like the infinity symbol, as if someone had pinched the middle. I touched it, and when I pulled away, there was fine gold dust on my fingers.

“This is what you wanted to show me?” I asked.

Gabe’s eyes shone, two small moons.

“This is what we’re breaking curfew for? We’re trespassing on Mr. Keller’s property—do you realize we could be suspended?”

Gabe clamped his jaw shut. His eyes flitted across my face the way they had through our group on the hill. Then a different, steely sheen came over them; it was as if someone had let down the blinds.

Читать дальше