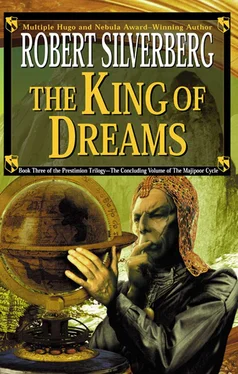

The King of Dreams

by Robert Silverberg

And Lord Stiamot wept when he heard them singing the ballad of his great victory at Weygan Head, because the Stiamot of which they sang was not the Stiamot he knew. He was not himself any more. He had been emptied into legend. He had been a man, and now he was a fable.

—AITHIN FURVAIN

The Book of Changes

For Jennifer and Peter—such twists, such turns!

“That has to be what we’re looking for,” said the Skandar, Sudvik.

Gorn, standing at the edge of the cliff and pointing down the steep hillside with harsh jabbing motions of his lower left arm. They had reached the crest of the ridge. The underlying rock had crumbled badly here, so that the trail they had been following terminated in a rough patch covered with sharp greenish gravel, and just beyond lay a sudden drop into a thickly vegetated valley. “Vorthinar Keep, right there below us! What else could that building be, if not the rebel’s keep? And easy enough for us to set it ablaze, this time of year.”

“Let me see,” young Thastain said. “My eyes are better than yours.” Eagerly he reached for the spyglass that Sudvik Gorn held in his other lower arm.

It was a mistake. Sudvik Gorn enjoyed baiting the boy, and Thastain had given him yet another chance. The huge Skandar, better than two feet taller than he was, yanked the glass away, shifting it to an upper arm and waving it with ponderous playfulness high above Thastain’s head. He grinned a malicious snaggletoothed grin. “Jump for it, why don’t you?”

Thastain felt his face growing hot with rage. “Damn you! Just let me have the thing, you moronic four-armed bastard!”

“What was that? Bastard, am I? Bastard? Say it again?” The Skandar’s shaggy face turned dark. He brandished the spyglass now as though the tube were a weapon, swinging it threateningly from side to side. “Yes. Say it again, and then I’ll knock you from here to Ni-moya.”

Thastain glared at him. “Bastard! Bastard! Go ahead and knock me, if you can.” He was sixteen, a slender, fair-skinned boy who was swift enough afoot to outrace a bilantoon. This was his first important mission in the service of the Five Lords of Zimroel, and the Skandar had selected him, somehow, as his special enemy. Sudvik Gorn’s constant maddening ridicule was driving him to fury. For the past three days, almost from the beginning of their journey from the domain of the Five Lords, many miles to the southeast, up here into the rebel-held territory, Thastain had held it in, but now he could contain it no longer. “You have to catch me first, though, and I can run circles around you, and you know it. Eh, Sudvik Gorn, you great heap of flea-bitten fur!”

The Skandar growled and came rumbling forward. But instead of fleeing, Thastain leaped agilely back just a few yards and, whirling quickly, scooped up a fat handful of jagged pebbles. He drew back his arm as though he meant to hurl them in Sudvik Gorn’s face. Thastain gripped the stones so tightly that their sharp edges bit into the palm of his hand. You could blind a man with stones like that, he thought.

Sudvik Gorn evidently thought so too. He halted in mid-stride, looking baffled and angry, and the two stood facing each other. It was a stalemate.

“Come on,” Thastain said, beckoning to the Skandar and offering him a mocking look. “One more step. Just one more.” He swung his arm in experimental underhand circles, gathering momentum for the throw.

The Skandar’s red-tinged eyes flamed with ire. From his vast chest came a low throbbing sound like that of a volcano readying itself for eruption. His four mighty arms quivered with barely contained menace. But he did not advance.

By this time the other members of the scouting party had noticed what was happening. Out of the corner of his eye Thastain saw them coming together to his right and left, forming a loose circle along the ridge, watching, chuckling. None of them liked the Skandar, but Thastain doubted that many of the men cared for him very much either. He was too young, too raw, too green, too pretty. In all probability they thought that he needed to be knocked around a little—roughed up by life as they had been before him.

“Well, boy?” It was the hard-edged voice of Gambrund, the round-cheeked Piliplok man with the bright purple scar that cut a vivid track across the whole left side of his face. Some said that Count Mandralisca had done that to him for spoiling his aim during a gihorna hunt, others that it had been the Lord Gavinius in a drunken moment, as though the Lord Gavinius ever had any other kind. “Don’t just stand there! Throw them! Throw them in his hairy face!”

“Right, throw them,” someone else called. “Show the big ape a thing or two! Put his filthy eyes out!”

This was very stupid, Thastain thought. If he threw the stones he had better be sure to blind Sudvik Gorn with them on the first cast, or else the Skandar very likely would kill him. But if he blinded Sudvik Gorn the Count would punish him severely for it—quite possibly would have him blinded himself. And if he simply tossed the stones away he’d have to run for it, and run very well, for if Sudvik Gorn caught him he would hammer him with those great fists of his until he was smashed to pulp; but if he fled then everyone would call him a coward for fleeing. It was impossible any way whichever. How had he contrived to get himself into this? And how was he going to get himself out?

He wished most profoundly that someone would rescue him. Which was what happened a moment later.

“All right, stop it, you two,” said a new voice from a few feet behind Thastain. Criscantoi Vaz, it was. He was a wiry, broad-shouldered gray-bearded man, a Ni-moyan: the oldest of the group, a year or two past forty. He was one of the few here who had taken a liking of sorts to Thastain. It was Criscantoi Vaz who had chosen him to be a member of this party, back at Horvenar on the Zimr, where this expedition had begun. He stepped forward now, placing himself between Thastain and the Skandar. There was a sour look on his face, as of one who wades in a pool of filth. He gestured brusquely to Thastain. “Drop those stones, boy.” Instantly Thastain opened his fist and let them fall. “The Count Mandralisca would have you both nailed to a tree and flayed if he could see what’s going on. You’re wasting precious time. Have you forgotten that we’re here to do a job, you idiots?”

“I simply asked him for the spyglass,” said Thastain sullenly. “How does that make me an idiot?”

“Give it to him,” Criscantoi Vaz told Sudvik Gorn. “These games are foolishness, and dangerous foolishness at that. Don’t you think the Vor-thinar lord has sentries aplenty roving these hills? We stand at risk up here, every single moment.”

Grimacing, the gigantic Skandar handed the glass over. He glowered at Thastain in a way that unmistakably said that he meant to finish this some other time.

Thastain tried to pay no attention to that. Turning his back on Sudvik Gorn, he went to the very rim of the precipice, dug his boots into the gravel, and leaned out as far as he dared go. He put the glass to his eye. The hillside before him and the valley below sprang out in sudden rich detail.

It was autumn here, a day of strong, sultry heat. The lengthy dry season that was the summer of this part of central Zimroel had not yet ended, and the hill was covered with a dense coat of tall tawny grass, a sort of grass that had a bright glassy sheen as though it were artificial, as if some master craftsman had fashioned it for the sake of decorating the slope. The long gleaming blades were heavy with seed-crests, so that the force of the warm south wind bent them easily, causing them to ripple like a river of bright gold, running down and down and down the slope.

Читать дальше