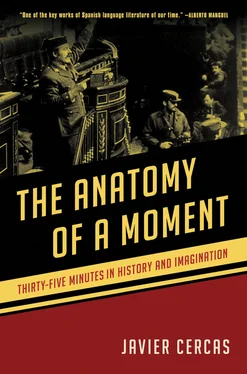

That is the scene: in order to protect his battered self-esteem, and that of his army, Gutiérrez Mellado always denied having been the victim of that outrage, but two years later he could not repeat the denial, because on the evening of 23 February the television cameras filmed the kind of affront, with more or less attenuating variants, that he’d become very familiar with in the privacy of the barracks. In this sense, as well, his gesture of confronting the golpistas in the Cortes chamber was a summary or an emblem of his political career; for this reason, it was the final battle of a merciless war against his own comrades that left him exhausted, ready for the scrap heap: like Adolfo Suárez, on 23 February Gutiérrez Mellado was a man who was politically finished and personally broken, his morale at a low ebb and his nerves undone by five years of daily skirmishes. It’s possible, however, that on 23 February the general was at the same time a happy man: that evening Adolfo Suárez was giving up power, and with his fall he had promised to give up a political career that without Adolfo Suárez he might never have embarked on.

He kept his promise: he was not prevented from doing so by Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo, who upon taking Suárez’s place as Prime Minister proposed he should stay on in the government, nor by Suárez himself, who tried to recruit him for the party with which he returned to politics after 23 February, and Gutiérrez Mellado prepared to spend the rest of his days in retirement, with nothing else to do but preside over charitable foundations, play long games of cards with his wife and spend long summers in Cadaqués with his Catalan friends. During his five years of political work many of his comrades-in-arms had loathed him for trying in vain to put an end to Franco’s Army and for successfully planning the bases of the Army of democracy; his retirement did not attenuate that feeling: the first request of the senior commanders of the Army to the Minister of Defence after he left government was that the general not come near their units, and not long after Gutiérrez Mellado had left his position as Deputy Prime Minister he had to give up organizing an act of redress conceived to counteract a renewed press campaign against him for fear that the proposal would divide the Armed Forces. He never set foot in an Army barracks again, except for the day when the Academy where he had done his officer training paid him a last-minute homage and the general was able to experience — at least while listening without shedding a single tear to the five-minute standing ovation that day from the cadets who filled the auditorium — the fictitious and sentimental certainty that all the unpleasantries of his years in government were justified. He died a short time after that misleading day, on 15 December 1995, when the Opel Omega he was driving to Barcelona to deliver a speech skidded on the ice around a curve and went off the road. With him disappeared the most loyal politician Adolfo Suárez ever had at his side, the last Spanish soldier to occupy a seat in the Cortes, the last brass hat in the history of Spain. Those who used to see him in his final years remember a humble, diminished, quiet and slightly absent man, who never gave statements to the press, who never spoke of politics, who never mentioned 23 February. He didn’t like to recall that evening, undoubtedly because he didn’t consider his gesture of confronting the mutinous Civil Guards as a gesture of courage or grace or rebellion, or even as a sovereign gesture of liberty or as an extreme gesture of contrition or as an emblem of his career, but simply as the greatest failure of his life; but whenever anyone managed to get him to talk about it he dismissed it with the same words: ‘I did what they taught me at the Academy.’ I don’t know if he ever added that the man in charge of the Academy where they taught him that was General Francisco Franco.

Returning to an image in the film: standing, with his arms hanging at his sides and defying the six Civil Guards riddling the Cortes chamber with bullets, General Gutiérrez Mellado — as much as if he wants to prevent the rebels from entering the premises as to subjugate military power to civilian power — seems to want to protect with his own body the body of Adolfo Suárez, sitting behind him in the solitude of his prime ministerial bench. That image is another summary or emblem: the emblem or summary of the relationship between those two men.

Gutiérrez Mellado’s loyalty to Adolfo Suárez was an unconditional loyalty from the beginning to the end of his political career. This can in part be attributed to the sense of gratitude and discipline of Gutiérrez Mellado, whom Suárez had turned into the highest-ranking military officer in the country after the King and the second most powerful man in the government; it’s likely that it was due to the total confidence that he placed in Suárez’s political wisdom and in his courage, his youth and his instinct. Suárez and Gutiérrez Mellado were nevertheless, aside from the political task uniting them, two opposite men in almost every respect: both, it’s true, shared a rock-solid Catholic faith, both cultivated a certain dandyism, both were thin, frugal and hyperactive, both loved football and the cinema, both were good card players; but their affinities practically finished there: the first was an expert in the ruses of the Spanish card game mus and the second in the more aristocratic bridge, the first came from a provincial Republican family and the second was from pure Madrileño stock and a good monarchist family, the first was a disastrous student and the second got straight As, the first was always a professional of power and the second was always a military professional, the first possessed, in short, political intelligence, personal charm, a gift for handling people, the cheek of a neighbourhood posse leader that he used to practise the art of seduction with indiscriminate skill, while the technical intelligence and sobriety of character of the second tended to confine his social life to the circle of his family and a few friends. They were also separated by a more obvious and more important difference: Suárez was exactly twenty years younger than Gutiérrez Mellado; they could have been father and son, and it’s almost impossible to resist interpreting the relation that united them as a strange and unbalanced paternal-filial relationship in which the father acted as a father because he protected the son but he also acted as the son because he didn’t question the other’s orders or doubt the validity of his opinions.

Gutiérrez Mellado’s political devotion to Adolfo Suárez must have begun the first time they spoke, or at least that’s how the general liked to remember it. It’s likely their paths had crossed at some point towards the end of the 1960s, when Suárez was running Radiotelevisión Española and flattering the military with programmes about the Army broadcast during prime time and with bouquets of roses he sent to their wives with notes apologizing for taking up their husbands’ time in off-duty hours, but it wasn’t until the winter of 1975 that they were alone together for the first time. During that period, with Franco recently deceased, Suárez had just been named Minister Secretary-General of the Movimiento in the King’s first government; for his part, Gutiérrez Mellado had already been a major general for several months and the government’s delegate in Ceuta, and on one of his trips to the capital he requested a meeting with the new minister to talk to him about a sports centre to be built in the city. Suárez received him, and a meeting that should have been a mere formality went on for several hours, at the end of which the general left the office at 44 Calle Alcalá dazzled by the young minister’s irresistible charm, original language and clarity of ideas, so at the beginning of July, when Suárez was put in charge of forming a government to the distressed surprise of most of the country, Gutiérrez Mellado might have been surprised, but not distressed, because by then he was already convinced of the exceptional worth of the new Prime Minister. Just three months later, Suárez summoned him to his side to turn him into his bodyguard and right-hand man in one, and nothing would ever come between them again. Gutiérrez Mellado was the first Deputy Prime Minister and the only unchanging minister of the six governments Suárez formed, but the friendship Suárez and Gutiérrez Mellado struck up was not just political. Not long after he joined the government, Gutiérrez Mellado moved with his family into one of the buildings that made up the Moncloa complex, where Suárez’s family home was already established; from then on, barely a day passed when they didn’t see each other: they worked next door to each other, and as time went on they began to share not only their workdays but also their leisure time, united by a respectful privacy that did not preclude confidences or long familiar silences, and only grew stronger during the months leading up to the coup while Suárez was every day losing, amid the ruins of his power and prestige, political allies, close collaborators and friendships that had lasted years. In those final moments of Suárez’s premiership and of Gutiérrez Mellado’s own political career he was, as well as politically finished and personally broken, a perplexed man: he didn’t understand the country’s ingratitude to the Prime Minister who had brought the dictatorship to an end and constructed the democracy; he understood the irresponsible frivolity of the political class even less — especially that of the members of the Prime Minister’s government — embroiled in the foolish struggle for power while democracy was crumbling around them. That’s why he was trying to pacify the internal rebellions of the UCD though no one paid him any attention, and that’s why at least on one occasion and with the very same result he took advantage of Suárez’s absence from a Cabinet meeting to shout angrily at its members and demand their loyalty to the man who had put them in their posts. Two anecdotes that speak for themselves date from that time. The first happened at five in the afternoon on 29 January 1981 in Moncloa, when, after Suárez announced his resignation to his ministers in a specially called Cabinet meeting, Gutiérrez Mellado stood up from his chair and improvised a very short speech that concluded with this request: ‘May God reward you, Prime Minister, sir, for the service you have done for Spain’; the sentence was sincere, if not eloquent: what is eloquent is that the meeting should have broken up immediately without any other minister pronouncing a single public word of consolation or support for the resigning Prime Minister. The second anecdote is without a precise date or location, but it almost certainly took place in Moncloa, perhaps in the two weeks previous to the first one; if that is the case, it must have taken place in a half-renovated office that Suárez began to use then in the back part of the residence, an enormous tumbledown hall with huge temporary windows through which the winter wind blew in and with loose wires hanging out of the walls that looked like the work of a decorator given the task of turning that space into a metaphor of the dilapidation of Adolfo Suárez’s final months in government. It could have been there and then, as I say, but it also might not have been: after all reality lacks the slightest decorative inclination. In any case it deserved to be there and then where, as Suárez himself recalled in public after the general’s death, he said to him at the end of a conversation or inventory of setbacks and desertions: ‘Tell me the truth, Prime Minister: apart from the King, you and me, is there anyone else on our side?’

Читать дальше