* There are likewise indications that, along with the CESID agents, agents of the Civil Guard Information Service (SIGC) under the command of Colonel Andrés Cassinello participated in the seizure of the Cortes. According to a report by one member of that service published in the newspapers in 1991, at five o’clock on 23 February several officers and twenty Civil Guards of the Operations Group of the SIGC under the command of a lieutenant began to deploy in the Cortes and vicinity, and at five thirty had already combed the area to be sure that, when the moment came, the police in charge of the building’s security would not oppose the entry of Lieutenant Colonel Tejero and his Civil Guards. This information has never been refuted.

PART TWO. A GOLPISTA CONFRONTS THE COUP

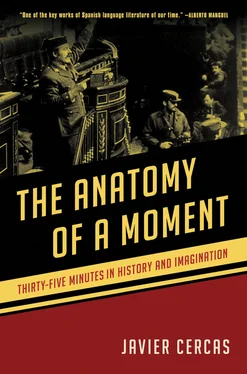

The frozen image shows the deserted chamber of the Congress of Deputies. Or almost deserted: in the centre of the image, leaning slightly to the right, solitary, statuesque and spectral in a desolation of empty benches, Adolfo Suárez remains seated on his blue prime minister’s bench. On his left, General Gutiérrez Mellado stands in the central semicircle, his arms hanging down at his sides, his back to the camera, looking at the six Civil Guards who shoot off their guns in silence, as if he wanted to prevent them from entering the chamber or as if he were trying to protect the body of his Prime Minister with his own body. Behind the old general, closer to the viewer, another two Civil Guards spray the chamber with submachine-gun fire while, pistol in hand, from the steps of the speakers’ rostrum, Lieutenant Colonel Tejero demands with gestures of alarm and inaudible shouted orders that his men stop the shooting that is pulverizing the instructions he has received. Above Prime Minister Suárez a few hands of hidden deputies appear between the uninterrupted red of the benches; in front of the Prime Minister, under and around a table covered with open books and a lit oil lamp, three stenographers and an usher curl up on the elaborate carpet of the central semicircle; closer, in the lower part of the image, almost blending in with the blue of the government benches, the crouching backs of a few ministers can be distinguished: a thread of crustacean shells. The whole scene is wrapped in a scant, watery, unreal light, as if it were going on inside an aquarium or as if the chamber’s only illumination came from the baroque cluster of spherical glass lampshades that hang from one wall, in the top right of the image; perhaps for this reason the whole scene also has a suggestion of a dance or a funereal family portrait and a hunger for meaning not satisfied by the elements that compose it or by the fiction of eternity that lends it its illusory stillness.

But if we unfreeze the image the stillness vanishes and reality regains its course. Slowly, while the shots grow more intermittent, General Gutiérrez Mellado turns, puts his hands on his hips, turning his back on the Civil Guards and Lieutenant Colonel Tejero, observes the abandoned chamber, like a punctilious officer taking visual stock of the destruction when the battle has not yet entirely concluded; meanwhile, Prime Minister Suárez leans back in his seat, straightening up a little, and the lieutenant colonel finally manages to get the Guards to obey his orders and the chamber is overtaken by a silence exaggerated by the recent din, as dense as the silence that follows an earthquake or a plane crash. At this moment the angle changes; the image we now see shows the lieutenant colonel from the front, with his pistol held high, standing on the stairs to the speakers’ rostrum; on his left, the Secretary of the Congress, Víctor Carrascal — still with the papers on his lap with the list of deputies that only a few seconds ago he was reciting monotonously during the investiture vote — watches in panic, lying on the ground, as two Civil Guards point their weapons at General Gutiérrez Mellado, who watches them in turn with his hands on his hips. Then, noticing out of the blue that the old general is still there, standing defiantly, the lieutenant colonel rushes down the stairs, pounces on him from behind, grabs him by the neck and tries to force him to the ground before the eyes of two Civil Guards and Víctor Carrascal, who at this moment hides his face in his arms as if he lacks the courage to see what is going to happen or as if he feels an incalculable shame at not being able to prevent it.

The angle changes again. It is also a frontal view of the chamber, but wider: the deputies lie tucked under their benches and the heads of a few of them cautiously peek over to see what’s going on in the central semicircle, in front of the speakers’ rostrum, where the lieutenant colonel has not managed to fell General Gutiérrez Mellado, who has stayed on his feet holding on with all his might to the armrest in front of the ministers’ bench. Now he is surrounded by the lieutenant colonel and three Civil Guards, pointing their guns at him, and Prime Minister Suárez, barely a metre from the general, stands up from his seat and approaches him, also holding on to the armrest: for a moment the Civil Guards seem to be about to fire; for a moment, on the armrest in front of their bench, the hand of the young Prime Minister and the hand of the old general seem to seek each other, as if the two men wanted to face up to their destiny together. But the destiny does not arrive, the shots do not arrive, or not yet, although the Civil Guards close in round the general — no longer four but eight of them now — and, while one of them insults him and shouts the demand that he obey and lie down on the carpet of the central semicircle, the lieutenant-colonel approaches him from behind and trips him and this time almost manages to throw him down, but the general resists again, clinging to the armrest as to a life raft. Only then does the lieutenant colonel give up and he and his Guards walk away from the general while Prime Minister Suárez seeks his hand again, takes it for an instant before the general pulls away angrily, without taking his eyes off his aggressors; the Prime Minister, however, insists, tries to calm his rage with words, begs him to return to his seat and makes him see reason: taking him by the hand as if he were a child, pulls him towards him, stands up and lets him pass, and the old general — after unbuttoning his jacket with a gesture that reveals his white shirt, his grey waistcoat and his dark tie — finally sits down in his seat.

There is a second translucent gesture here that perhaps like the first contains many gestures. Like Adolfo Suárez’s gesture of remaining seated on his bench while the bullets whizz around him in the chamber, General Gutiérrez Mellado’s gesture of furiously confronting the military golpistas is a courageous gesture, a graceful gesture, a rebellious gesture, a supreme gesture of liberty. Perhaps it might also be, in a manner of speaking, a posthumous gesture, the gesture of a man who knows he is going to die or that he’s already dead, because, with the exception of Adolfo Suárez, since the advent of democracy no one has stockpiled as much military hatred as General Gutiérrez Mellado, who as soon as the shooting started perhaps felt, like almost all of those present, that it could only end in a massacre and, supposing he were to survive it, the golpistas would not take long to get rid of him. I don’t believe it is, however, a histrionic gesture: although he’d been practising politics for the last five years, General Gutiérrez Mellado was never essentially a politician; he was always a soldier, and therefore, because he was always a soldier, his gesture that evening was above all a military gesture and therefore also in some way a logical, obligatory, almost fatal gesture: Gutiérrez Mellado was the only soldier present in the chamber and, like any soldier, he carried in his genes the imperative of discipline and could not tolerate soldiers’ insubordination. I’m not noting this fact to detract from the general in any way; I do so only to try to pin down the significance of his gesture. A significance that on the other hand we might not be able to pin down entirely if we don’t imagine that, while he is facing up to the golpistas , refusing to obey them or while shouting his demand that they leave the Cortes, the general could see himself in the Civil Guards defying his authority by shooting over the chamber, because forty-five years earlier he had disobeyed the genetic imperative of discipline and had rebelled against the civilian power embodied in a democratic government; or in other words: perhaps General Gutiérrez Mellado’s fury is not made only of a visible fury against some rebellious Civil Guards, but also of a secret fury against himself, and perhaps it wouldn’t be entirely illegitimate to understand his gesture of confronting the golpistas as an extreme gesture of contrition by a former golpista .

Читать дальше